How should you write a sentence?

How should you write a sentence?

Well, most guides will start off with 10,000 ways NOT to write a sentence.

You know, the finger-wagging schoolmarm that lectures you about avoiding fragments and comma splices and run-ons.

Ugh. That’s so negative. I prefer to focus on all the beautiful ways that you CAN write a sentence (trust me, there’s a lot!)

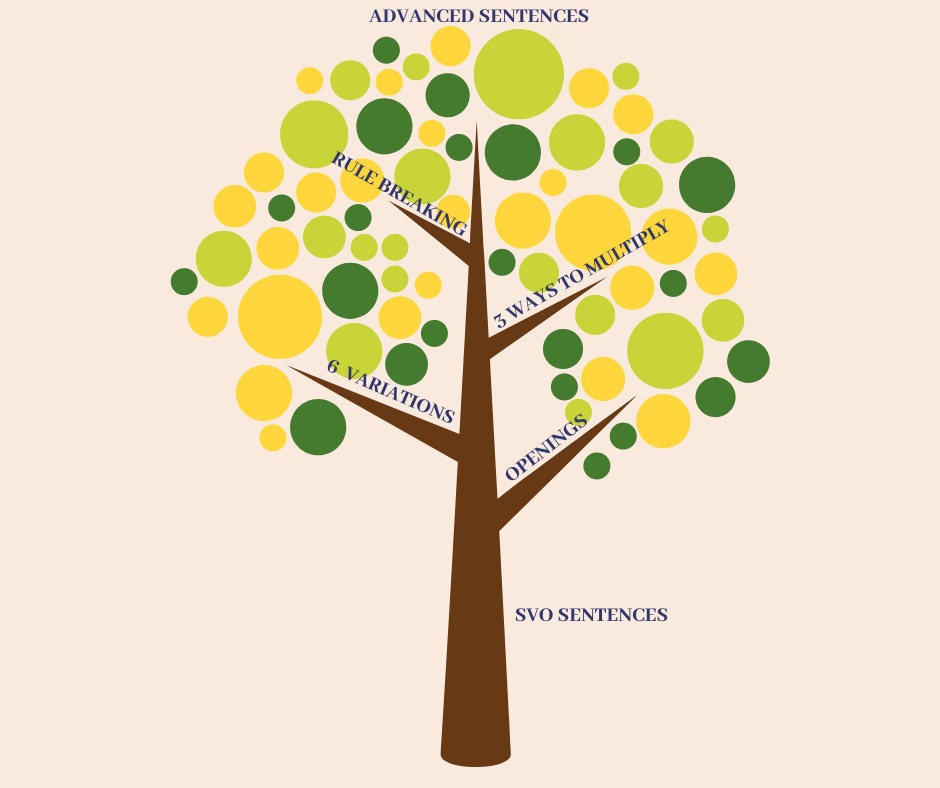

What I’m going to show you in this post is 16 branches of a “Sentence Tree.” This is where you start with a single simple sentence, and spin it off into a few variations, and then a few more variations off of that, until you have a whole tree full of branching variations.

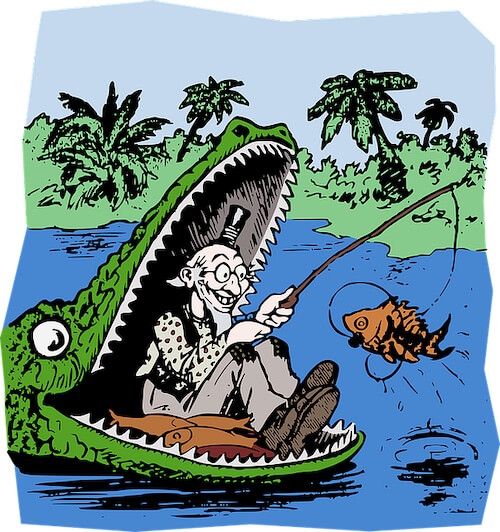

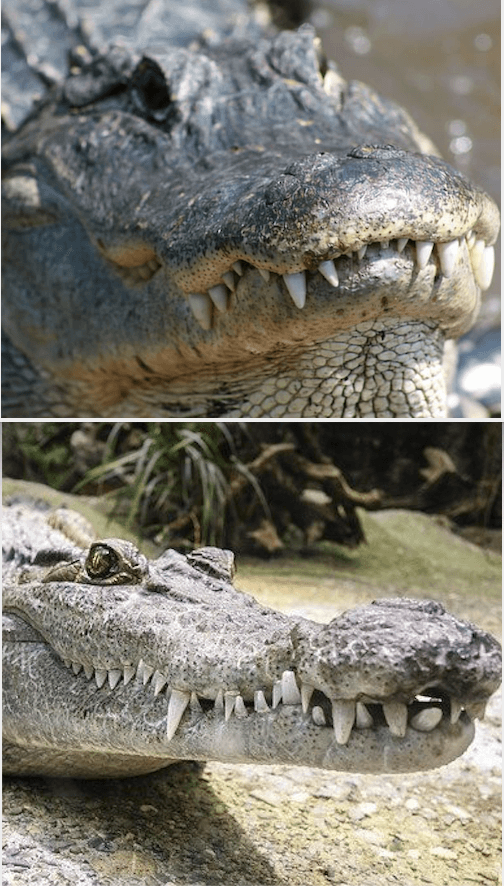

And every single one of these sentences is going to be about crocodiles, because it’s easier to see sentence variations when they’re all about the same topic. Plus, crocodiles are fun! Or at least dangerous, which is kind of fun.

And after you’re finished reading this, if you’d like to learn even more about sentences, check out my course, “How to Write a Splendid Sentence.”

And for our initial sentence, let’s start with something simple.

1. SVO Sentence

“That is not a crocodile.”

Now that one’s pretty easy. It’s a SVO sentence. Which means you’re writing “Subject, Verb, Object” in that order and that order alone.

- Subject = That

- Verb = Is

- Object = Crocodile

If you’re just starting out writing sentences, that’s an excellent place to start. It’s clear! It’s direct! Now you know what a crocodile isn’t!

But most of the time, if you just write SVO sentences, they get very, very boring, and you will put all of your readers to sleep.

Once they’re asleep, you have two options: you can shout/wave your hands/blow an air-horn, or … you can write different sentences.

2. Preposition Opening

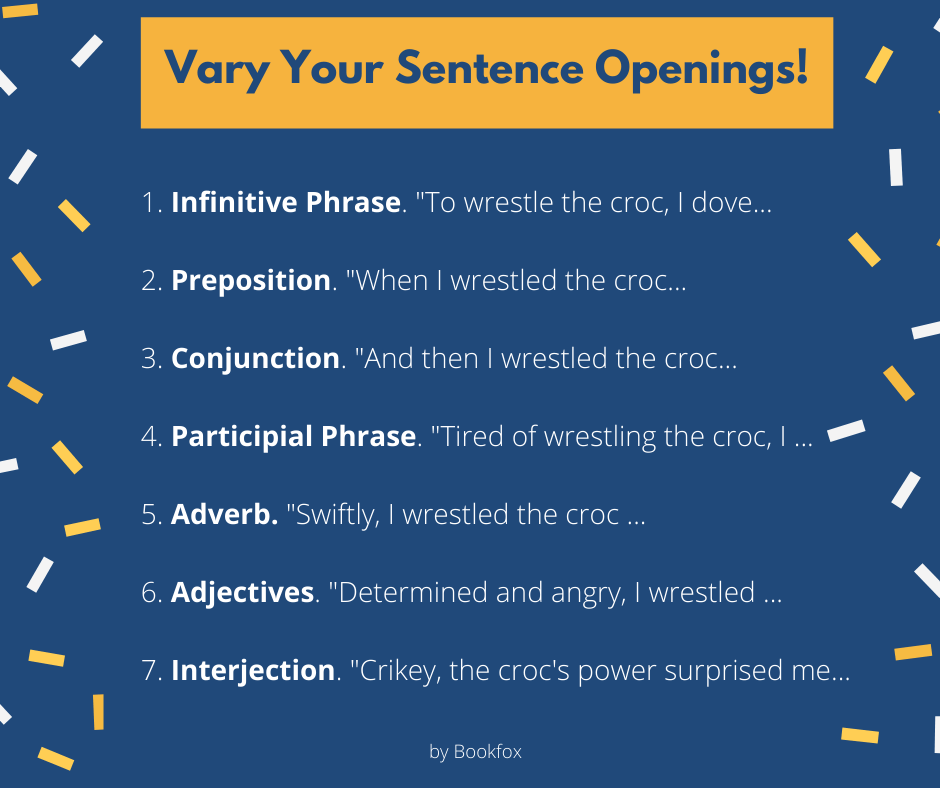

The next thing you should learn about how to write a sentence is to vary your sentence openings.

The next thing you should learn about how to write a sentence is to vary your sentence openings.

For instance, what about starting with a preposition? (Prepositions indicate direction, such as of, to, at, of, above, under…)

“In just a moment, he’d realize he should have obeyed the “no fishing” sign.”

Ah, what a lovely variation! If you slip a preposition sentence inside a paragraph full of SVO sentences, it will feel like a breath of fresh air.

Plus, it works like a mystery — the reader wants to know what’s going to happen in just a moment, and so they’re propelled to read to the end of the sentence, curious about what’s going to happen next.

In just a moment … What? Tell me already! I want to know!

3. Adverb Opening

Let’s look at another sentence variation opener. This time, we’ll use an adverb to launch this sentence.

Let’s look at another sentence variation opener. This time, we’ll use an adverb to launch this sentence.

“Carefully, he put the meat inside the crocodile’s mouth.”

That pause at the beginning of the sentence — a single word followed by a comma — is like the tension before a climax. We want to know exactly what he’s doing that requires such care, and so we keep reading.

Little tiny variations like this don’t seem to matter much, but they have a tremendous affect on the reader. It’s the difference between a reader getting bored and the reader thinking you’re a genius.

And in fact, there’s a whole bucketful of openings we can use on our sentences. If you carefully cycle through a bunch of them, it will go a long way toward not making your reader fall asleep.

And keeping your reader awake is a very good goal to shoot for.

So far, all three our sentences have been pretty short.

So far, all three our sentences have been pretty short.

Many short sentences in a row get boring.

Your reader’s eyes will start to glaze.

You need to provide some variety.

You need to write a longer sentence. (See — you just got tired of all those short sentences!)

How about we tackle more of a medium-length sentence? And what’s more, we’ll continue to avoid that simplistic SVO order, and try out a different structure.

Before we get to that, watch a video of me talking about sentences. This is the first video in my course, “How to Write a Splendid Sentence,” and I’ll talk about WHY writing great sentences is so important, and how to improve.

4. Standalone/Leaning Sentence

Now we’re going to learn how to write a Standalone/Leaning sentence.

Now we’re going to learn how to write a Standalone/Leaning sentence.

A leaning part of a sentence is one that can’t stand on its own (“While it’s not the best weather…”), while a standalone part of a sentence is one that can function all by itself (“We should still go skiing.”).

“When the zookeeper said she could have what she wanted, he didn’t expect she would bejewel herself.”

We start with the leaning part of the sentence — “When the zookeeper said she could have what she wanted…” (see how that’s not a finished thought?)

Then we end with the standalone part: “He didn’t expect she would bejewel herself.”

What’s great about a standalone/leaning sentence is that you can create a mystery. When you start with a leaning part of a sentence, grammatically the reader is eager to learn about the end of the sentence!

It’s like music when you’re playing an unresolved chord, and the listener is yearning for the resolving chord.

Still, I think we can do even better than that sentence.

5. Connector Sentence

Let’s break out the big guns and open up a can of whoop ass — a Connector sentence.

Let’s break out the big guns and open up a can of whoop ass — a Connector sentence.

A Connector sentence has a conjunction in it, like “And” an “or” or a “but.”

Check out this dope Connector sentence!

“He thought the crocodile was a baby, but it turned out to be much larger and much hungrier than he expected.”

We have two connectors: “But” and “And.” Without those Connector parts, we just have the straightforward SVO sentence of “He thought the crocodile was a baby.”

The true twist of the sentence comes with the “But,” because we learn that it’s large and hungry!

Ultimately, a Connector sentence lets you add in some contrasts and additional info, making your writing seem much more sophisticated and advanced, even though it isn’t a particularly difficult sentence to write.

And the great benefit of a Connector sentence is that you can keep on spinning out more and more sections — it’s such an easy way to connect parts of your sentence together. Want to keep it going? Just through in another “And” or another “But” or another “Or” and toss in more information.

6. Leaning + Connector Sentence

How about we take our sentence and turn it into a leaning AND connector sentence? Oh, now I’m just getting all crazy on you.

“Although the spacesuit designer had clearly not considered the shape of crocodile heads, Mr. Croc still wanted to step foot on the moon and plant a flag for all reptiles.”

Ultimately, connecting these strategies is the way to take your sentence writing skills from newbie level up to expert level.

As long as you understand any one of these individual techniques, you will be able to write increasingly complex sentences that incorporate three, four, or even five of these techniques at once.

7. Middle Child Sentence

Now, what about the middle of the sentence? The middle often gets a bad rap.

Now, what about the middle of the sentence? The middle often gets a bad rap.

We focus on the beginning, we focus on the end, but nobody focuses on the middle.

But an excellent way to create sentence variety is to spin out the middle with a “middle branch sentence.”

“The owner of the crocodile, who was a middle aged woman, said she’d applied too much whitening cream.”

This sentence is very easy to make. Take a simple SVO sentence and offer up a juicy tidbit in the middle. You can add as many as you want!

“The owner of the crocodile…

- who was a middle-aged woman,

- limping along with a cast on her leg,

- and who spoke in a New York accent,

…said she’d applied too much whitening cream.”

Yeah, I love sentences too. That’s why I created this online course about how to write a better sentence.

Yeah, I love sentences too. That’s why I created this online course about how to write a better sentence.

If you want to feel more confident about your writing, this is the course for you.

8. The Parallel Sentence

A simple parallel sentence has two parts, each of which mirror the other.

It’s a classic pattern, and it makes you sound smart without even breaking a sweat.

“Crocodiles smile with interlocking teeth, while alligators smile with only their upper teeth.”

Both halves the sentence start with a subject: Crocodiles, Alligators. Both have a verb of smile, and end on teeth.

The only difference is the interlocking vs. upper.

The beauty of a parallel sentence is that it’s full of repetition, mainly repetition in the form of key words and the shape of both halves.

It’s kind of like poetry, in that the sentence is flowing out of a pre-determined shape.

9. The Metaphor Sentence

Metaphor is the art of comparing dissimilar things, and Plato said it was the supreme marker of intelligence.

Metaphor is the art of comparing dissimilar things, and Plato said it was the supreme marker of intelligence.

Maybe it is, and metaphor certainly makes for incredible sentences. When I compiled my list of 100 beautiful sentences, someone commented and said 48 of them had metaphors or similes, and that wasn’t surprising: metaphors simply make sentences better.

“Dating a lawyer is a little like dancing with a crocodile: at any moment you might find that you’re no longer the partner, but the meal.”

Comparisons, as long as they’re highly unusual, have the chance to shock the reader. My main advice is not to overuse them — a few go a long way.

Three Multiply Techniques

Now that you have some basic sentence forms down, it’s time to spread your sentence wings!

A wonderful technique is to take one of the techniques above and simply do it multiple times in a sentence.

10. Connector Jamming

Now, it’s one thing to have a simple connector sentence. You know, throw in an And and an Or and a But. No big deal.

Now, it’s one thing to have a simple connector sentence. You know, throw in an And and an Or and a But. No big deal.

But what happens if you go absolutely crazy with Connectors? Well, then you start sounding very strange indeed, but that strangeness becomes your unique style. Readers come to appreciate that you sound different from other writers.

“He waddled out to the beach and sipped his drink and laid down his towel and applied lotion and crossed his legs and began to tan.”

Five “Ands” in that short sentence! Five!

That kind of repetition really sets the sentence apart.

What you don’t need to know is the fancy-pants term for this is called “Polysyndeton.”

What you do need to know is that by using a bunch of Connectors in a row, you’ll cast a spell over the reader and make them seem cast headlong into your writing dream, and heighten the action of your writing.

11. SVO Party

What if you feature a lot of SVO sentences in a row? Well, you’re certainly not creating any type of sentence variety.

What if you feature a lot of SVO sentences in a row? Well, you’re certainly not creating any type of sentence variety.

But guess what? SVO sentences repeated have a kind of music to them. You’re creating a specific style.

Check out these three short SVO sentences from Cormac McCarthy, in “No Country for Old Men”:

“Wells smiled. He leaned back in the chair and crossed his legs. He wore an expensive pair of Lucchese crocodile boots.”

They’re all short sentences. They all start with a subject, go on to a verb, and end with an object. It’s the absolute heart of simplicity with no variation. But it’s also kind of beautiful and musical, mainly due to its simplicity.

12. Tilting Sentence

A tilting sentence occurs when you stack a bunch of leaning sentence pieces together.

A tilting sentence occurs when you stack a bunch of leaning sentence pieces together.

“If she hadn’t gone down the river that day, and if she hadn’t decided to stop and watch that butterfly, and if she hadn’t daydreamed about the cute boy, and if she hadn’t picked a piece of mud from between her toes, and if she’d listened to her mother’s advice to never linger at the water’s edge, then she would probably still be alive right now, rather than digesting in a crocodile’s belly.”

It’s fun to do this because it creates this wonderful effect that tilts the reading experience, making the reader rush toward the end of the sentence because they want to find the resolution at the end of all these leaning parts.

It’s usually best to structure the leaning parts as an anaphora, meaning you list the same word at the beginning of each section (in this case, it’s “if.”)

Breaking the Rules

Okay, now that you’ve got your sentence feet under you, let’s branch out further on this sentence tree, and explore breaking some rules.

Why? Because following the rules is boring. And because most great writers break the rules (this is honestly what makes them great!)

You really can’t do a full sentence tree variation without breaking some rules.

13. Create Fragments

Fragments get the bulk of red ink from school teachers. Write complete sentences, they say!

Fragments get the bulk of red ink from school teachers. Write complete sentences, they say!

But there is a time and place to write an incomplete sentence. Actually, incomplete sentences can be quite beautiful.

“The crocodile yawned and showed a huge rack of teeth. Gleaming teeth. Jagged teeth. Terrifyingly sharp teeth.”

Now, I just threw in that first sentence so you can see how these fragments connect to full sentences. But the three fragments afterwards end up modifying and explaining the full sentence before.

Are they all mistakes? Well, technically, yes. They’re not complete sentences.

But are they beautiful? That is the real question, and I think the answer is yes.

By creating fragment sentences, these very brief interludes pockmarked with periods, you make the reader slow down and really chew the words. It creates a very specific effect on the reader, and that’s quite useful!

14. Splice Your Commas

I went to the store, I bought milk.

I went to the store, I bought milk.

See that comma in the middle? That’s called a comma splice.

It’s a five-alarm mistake because you can’t connect two standalone sentences with just a comma. It’s a mistake just like fragments and run-ons are a mistake.

But … there are all sorts of ways you can make this mistake beautiful.

- “You’re a tough crocodile, that’s clear enough.”

- “Bob didn’t like crocodiles, he never had.”

- “Today it’s all about crocodiles, tomorrow will be all alligators.”

You could separate each of these into two sentences, but it certainly loses the freewheeling colloquial nature of the sentence. A formal period seems more stiff and proper, and perhaps you want a looser feel to your sentence.

When you do use comma splices, just make sure that both sentences are very short (this doesn’t work with longer halves).

Take an online course in sentence writing that will build your writing confidence.

Take an online course in sentence writing that will build your writing confidence.

- 28 Videos

- Taught by an editor

- Practice quizzes, bonus PDFs, and writing challenges

Advanced Sentences

You probably don’t want to keep reading, unless you want to be smart and write well.

But if you do want to be smart and write great sentences, by all means, keep reading let me pull back the curtain on some sweet techniques.

15. Combo Sentence

Remember that most of the techniques above in the sentence tree above can be combined to form super combo sentences (if you’re a child of the 80s, think of all the Transformers coming together to form a Combiner Superbot!).

Remember that most of the techniques above in the sentence tree above can be combined to form super combo sentences (if you’re a child of the 80s, think of all the Transformers coming together to form a Combiner Superbot!).

Writing Exercise: I challenge you to pick any 3 techniques above and take a stab at combining them.

I’ll show you an example to get you started.

Out of a hat, I’ve picked these three to combine: Adverb Opening, SVO, and Leaning/Standalone.

“Regrettably, he could feel his hair tickle the crocodile’s tonsils, and though sticking his head in the crocodile’s mouth was not his first mistake, it would be his last.”

- Adverb Opening: Regrettably

- SVO: He could feel his hair tickle the crocodile’s tonsils

- Leaning/Standalone: “though sticking his head… it would be his last.”

16. Long Sentences

I’ve written a ton about long sentences, and you can check out my list of long sentences over 100 words.

In fact, if you follow that link, you can read Steven Millhauser’s 1,147-word long sentence (!!!) “Home Run,” actually mentions alligators, though it’s only a “see ya later, alligator,” type of reference.

But ultimately, you can really show off your writing chops if you can pull off a 50 word or 75 word sentence.

Plus, you can give the reader a really heady experience of reading you — you can mimic the energy of feeling in a fight, or the rush of traveling fast, or the experience of making love.

Frequently Asked Questions

I was told never to write a long sentence because it’s a run on. Is that true?

No, that’s a myth. A run-on sentence is one that is grammatically incorrect because it’s two complete sentences smashed together without punctuation. You can write sentences that are pages long without ever creating a run-on.

Should I never use semi-colons or colons?

Well, this is hotly debated. Some writers love semi-colons; others hate them. Personally, I think it’s fine to use colons or semi-colons, but sparingly — you don’t want to overuse them.

How do I discover my personal writing style?

Listen to how you speak. How you speak — the rhythms, the cadences, the diction level, the slang — it all provides the best clue for how you should write on the page. Essentially, you want to be your essential self when you write, and not try to create a false persona.

How do I improve at writing complex sentences?

Read a great deal, and read slowly. Pick out sentences you like and dissect them to see how they were made. Keep a list of your favorite sentences and see if you can find any commonalities between them.

English isn’t my first language. How can I get better at writing sentences?

Other than vocabulary, syntax is probably one of the hardest things to master in the English language — the order of words. There isn’t any shortcut to mastering the order, but the more you speak, read, and write, the closer you’ll get to writing gorgeous sentences.

Quiz Time!

Can you identify the patterns of sentences below? If you use the techniques you’ve learned above, you should be able to figure them out.

Quiz 1. “When a hunter or trapper begins kicking at a crocodile, its body curls to accommodate the withdrawing foot.”

Quiz 1. “When a hunter or trapper begins kicking at a crocodile, its body curls to accommodate the withdrawing foot.”

– Karen Russell, “Swamplandia”

What type of sentence is this? Don’t look lower unless you’ve got an answer (or at least a guess).

Karen Russell, whose book “Swamplandia” is all about an amusement park full of crocodiles, created this sentence which is a great example of the standalone/leaning type of sentence.

“When a hunter/trapper begins kicking at a crocodile…”

That’s the leaning part. If you read it out loud, it’s definitely not finished.

“Its body curls to accommodate the withdrawing foot.”

See? See? That’s the standalone part of the sentence. It’s a complete sentence. And it’s the most surprising part of the sentence, which is why it’s the end of the sentence. I can’t even believe crocodiles are so malleable they’ll contour their bodies to mirror where someone has kicked them.

Quiz 2. “The owner of the crocodile, who was a German, looked at us with an air of extraordinary pride.”

– Fyodor Dostoevsky, “The Crocodile”

This one isn’t too hard, right?

This one isn’t too hard, right?

It’s a Middle Child Sentence.

We’ve got that “who was a German” which interrupts the basic SVO sentence about the crocodile owner.

Quiz 3. “Truth changes shape just as the crocodile eats away the moon.”

– Marlon James, “Black Leopard, Red Wolf”

Well…

Well…

If you’re guessing that he’s comparing truth changing to a crocodile eating the moon, then you would be on course to figure out that this is a metaphor sentence.

A very strange metaphor sentence, but hey — maybe it will make the reader do a double take.

Quiz 4. “On that map, made in the style of baroque panoramas, the area of the Street of Crocodiles shone with the empty whiteness that usually marks polar regions or unexplored countries of which almost nothing is known.”

– Bruno Schulz, “The Street of Crocodiles”

This is a tough one. I never said learning sentence types was going to be easy.

This is a tough one. I never said learning sentence types was going to be easy.

But you’re smart enough to figure it out.

Really study this sentence. Divvy up all the pieces.

Maybe look at the examples higher up in the post if you can’t figure it out.

Got a guess?

Okay, this is an example of a leaning + connector sentence.

First, the “Connector” part. See that “Or” in there? Yep, that’s a dead giveaway. “empty whiteness that usually marks polar regions OR unexplored countries of which almost nothing is known.”

Now, the Leaning part is the beginning. “On that map, made in the style of baroque panoramas…”

#

Great job if you identified those sentence patterns. Clearly, you’re learning a lot more about sentences, and I commend you!

5 gold stars for you. 25 high fives! And a hearty slap on the back.

Do you have any other questions about sentences?

Do you have any other questions about sentences?

I would LOVE LOVE LOVE to hear them in the comments below.

5 comments

Hi! I’m a young writer, really wanting to pursue publishing and writing my own books! I often catch myself using the common letter “I” at the beginning of so many of my sentences. I try to fix it or push it away by putting forth an action like, “Flinging the sheet off,” or “Grabbing my lunch,” but I seem to always come back to just “I.” If I could get some other recommendations, I would really appreciate it.

Hi Addisyn, yes, you’ve slipped into the repetition of SVO. I would recommend looking at the blue box of “Vary Your Sentence Openings” toward the top of this page and use some of those techniques.

Very informative, thank you. It was just what I was looking for. I would love to know how to use hyphens within the middle of sentences and more on different grammar uses. I’ve been reading a lot of Neil Gaiman and noticing that he uses a fair amount of longer sentences with colons, semi-colons, commas and “ands” all in one sentence. I’ll check out your list of sentences though too.

Neil Gaiman is great, and he definitely spins out some complex sentences. For em dashes/en dashes within a sentence (not hyphens) it would be an “Aside.” This is a little bit like a Middle Child sentence, or a sentence with parentheticals (like this) in the middle. I’m going to write an email about that, if you want to sign up for the “how to write better sentences” email (if you missed the pop-up, go to the Join the Bookfox Club page at the top of the blog.)

I have found this gem of the website so informative. Your writing itself overshadows some of the famous sentences that you quote. One day, when time permits, I will surely enrol in your course.