From Lord of the Rings to Star Wars, across sci-fi and fantasy, good worldbuilding is what makes genre fiction stand out.

Well-constructed worlds are legendary—they capture audience’s imaginations, and they make readers want to live in the story forever.

What would Terry Pratchett’s Discworld series be without the Discworld itself? What would The Wizard of Oz be without Oz?

Worldbuilding is a crucial part of a story’s setting, and most of all, it’s crucial to a story’s plot. In genre fiction especially, the setting takes on a whole new importance because it impacts the plot. Magic, new technology, mythical creatures, gods, tyrants, and otherworldly forces of nature can all come from a new world and, at the same time, directly affect it.

Still, it can be overwhelming. How can one person create a whole world, and how can you make sure it will be a good one? How do you know where to start?

As with most big tasks, the solution is to break it down into sections and use helpful strategies.

First, it’s important to learn about the different types of worldbuilding, so you know what your options are.

Hard Worldbuilding vs Soft Worldbuilding

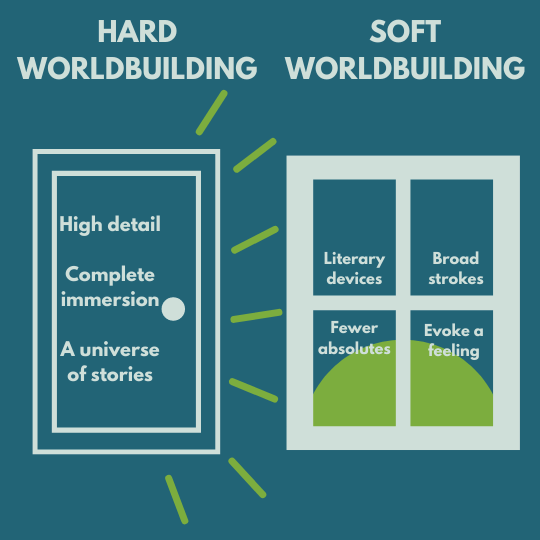

For as many types of storytelling there are, there are two main approaches to worldbuilding: hard worldbuilding and soft worldbuilding.

Brandon Sanderson, author of the Mistborn series, says that worldbuilding is like an iceberg. The tip of the iceberg is how much you show. The invisible bottom of the iceberg underwater is how much you know.

The difference between hard and soft worldbuilding comes down to how much information you reveal to the reader about the mechanics of your world—in other words, how much of the iceberg you choose to show.

Hard Worldbuilding

Hard Worldbuilding

Hard worldbuilding explains the mechanics of the world in great detail. You’re showing a lot of your iceberg, in all its majesty.

V.E. Schwab’s term for someone who prefers hard worldbuilding is a “door writer.” They give the reader a door into their world, allowing the reader to walk through the door and see absolutely everything.

Stories at the far end of hard worldbuilding get MMORPGs made about them. Think of Lord of the Rings, Game of Thrones, and Star Trek that hold entire made-up languages that end up on Duolingo.

These worlds feel real because the author shows us the “proof.” We get tons of information, enough that it feels like it could equal the amount of information we know about our own world. The history of whole countries, entire languages, complex politics, advanced technological systems, and intense rules of magic are revealed to such a degree that we can learn these details and play a game of Trivial Pursuit about them.

The benefits of the hard approach to worldbuilding are:

- There’s high detail and immersion in the world

- The world is concrete beyond the main character’s experience

- The main story feels like one small part of a universe full of stories

But there are also drawbacks are that you’re more likely to encounter:

- You might write yourself into corners

- It’s easier to get too involved in the details

- You might be more likely to fall into some of the pitfalls of worldbuilding

Soft Worldbuilding

In soft worldbuilding, the mechanics of the world are more figurative or implied. You’re only showing a little bit of your iceberg, but it’s still mesmerizing and leaves your audience intrigued by everything underneath.

Schwab calls soft worldbuilders “window writers.” The reader will never get the full view of the world, just a window into it, and they’ll have to infer things they cannot see. A window writer works with big concepts.

Think of worlds like:

- Schwab’s collection of Londons in Shades of Magic series

- the short stories of Kelly Link in Get in Trouble

In Get in Trouble, we get splashes of fantastical things. There is a summer house full of fairies that will reveal to you your heart’s desire, but the fairies are always unseen. We don’t learn about who they are, what their motivation is, or why our main character is magically compelled to take care of them. But: the story still makes sense to the reader within the logic of our character’s mind. There are still stakes, and the magic is still interesting.

The benefits of soft worldbuilding are that they allow the author to:

- Pique audience curiosity

- Lean more into literary devices

- Work in broad strokes

- Not worry too much about setting up rules or absolutes

- Work with a lower probability of losing the reader’s trust

And the possible drawbacks:

- Pitfalls like confusion or a lack of logic

- Glossing over parts of the world that a reader should have a grasp on

- Greater difficulty in earning the reader’s investment

How to use a combination of both

It’s possible to use a combination of hard and soft worldbuilding. Maybe one element of your story is defined in a hard style, while the rest of the world is softer.

The life and journey of your main character might be defined with hard worldbuilding. Maybe we get to learn all about their culture and traditions, maybe we learn some of their language. But the world outside our main story is more softly defined.

Soft worldbuilding around the edges of hard worldbuilding can make a world feel bigger. It can shave off some work for an author.

Two Main Pillars of Worldbuilding

Whether you’re doing hard worldbuilding or soft worldbuilding, it will inform the rest of the choices you make about which areas of your world you’ll focus on and how you’ll communicate them to your reader.

But still, this doesn’t answer the question of what one actually needs to start worldbuilding. When you’re faced with the task of fleshing out a world and fitting your story into it, it can be difficult to know where to start.

Let’s break it down.

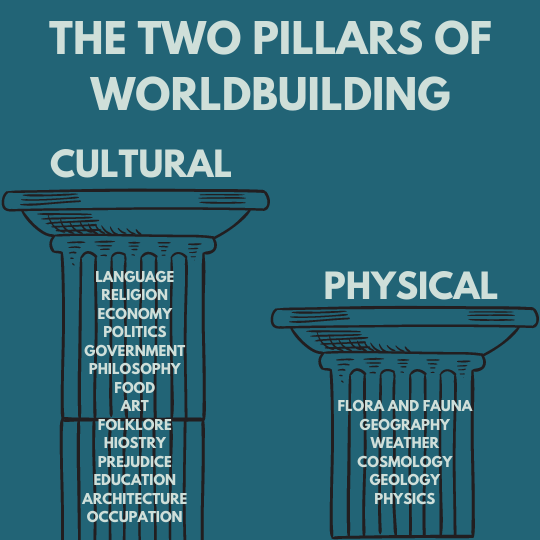

Returning to the advice of Brandon Sanderson, there are two main pillars of worldbuilding to consider: physical setting and cultural setting.

1. Physical setting: Environmental worldbuilding

Physical setting can include:

- Flora and fauna

- Geography

- Weather

- Cosmology

- Geology

- Laws of physics

You could think of this as the most literal part of worldbuilding. What makes up the ground your characters are standing on? Is there anything that’s hugely different from the world we live in?

Stories like Jurassic Park have physical setting as the centerpiece of the story. The existence of the park is central to the plot. And of course, the dinosaurs are some really interesting fauna that our characters have to reckon with.

2. Cultural setting: Character worldbuilding

Cultural setting can include:

- Language

- Religion

- Economy

- Politics and government

- Philosophy

- Food

- Art and music

- Folklore

- Gender roles

- Weapons and tech

- History

- Prejudices

- Education

- Architecture

- Occupations

This is the part of worldbuilding that is likely to be most active in your story and have the most to do with characters’ day-to-day lives and choices. Essentially, this is the world that your characters make for themselves. The people who populate your world will be making choices and taking action—throughout your story, and also long before your story begins. What are the consequences of those choices and actions, and how do they affect the culture of this world?

Cultural setting is also where you’ll usually find conflict in your plot.

Differences in politics, culture, philosophy can be a primary source of tension between characters. They can be the source of motivation for your main character that sends them on their journey.

“This may sound silly, but I like to wonder what people would have for breakfast–which people, as their breakfasts would be different–and where they would get those food items, and whether or not they would say a prayer over them, and how they would pay for them, and what they would wear during that meal, and, if cooked, how, and what sort of bed they would have arisen from, and what else they might be doing while having the breakfast–talking to someone (who), in person or on a device (what?), and who would be allowed to do that, and what they might feel safe in saying. Breakfast can take you quite far.” — Margaret Atwood

Margaret Atwood, author of The Handmaid’s Tale (and many other fantastic novels that play with dystopia and magical realism) digs into the details of cultural setting to uncover questions she has about her world. Even small details can be indicative of huge choices you’ve made about the culture of your world, so don’t overlook them. Be conscious of every cultural element that appears in your story, and see what you can use to your advantage.

If you’re feeling overwhelmed by how broad these two categories of cultural and physical setting are, it’s helpful to break it down even further.

8 Crucial Ingredients to Worldbuilding

1. Flora and Fauna

You’ve got a world—what’s living in it?

Flora and fauna include animals and plants—anything organic and alive. Will your story make something new out of something that’s familiar to us on earth?

Margaret Atwood advocates for drawing from real life, nature, and engaging with your own scientific curiosity for inspiration.

Is your world a lot like our current planet Earth? If so, what about it would be helpful to research or understand? And if your world is unlike earth or takes place in space, what phenomena can you draw from to make that experience feel more intensely real or interesting to your reader?

Consider the ways in which living beings might be just like the ones in our world, and the ways in which they might be totally different.

Phillip Pullman’s His Dark Materials books are a great example of using flora and fauna as a centerpiece of worldbuilding. In The Golden Compass, every character has a daemon, a physical animal companion that is a part of every human’s soul. The existence of daemons changes how readers view characters and animals in this world. They take on a new magical quality. Learning how daemons work, what they look like, and why, is one of the the most fascinating parts of the story.

2. Power and Politics

2. Power and Politics

The driving forces of culture in your world are likely rooted in systems of power.

“The world-building that really falls into place first is what I always describe as the sense of power—helping readers understand how power flows in the book. That could mean governmental power, personal power, magical power, whatever. But [determining how power flows] is going to determine how your characters behave on the page, and what they’re able or not able to do.” — Leigh Bardugo, author of the Grisha trilogy and The Ninth House

Government, class, and civil rights (or lack thereof) can all be huge parts of a story and sit at the center of your worldbuilding process.

Any dystopia, or any story where there’s a Resistance (like Star Wars or The Hunger Games) obviously has a lot to do with governmental and political power, who has it, and who’s using it for good or evil.

Another example of power determining how a world works is in Stardust by Neil Gaiman. In Stardust, a star falls from the sky and we learn that her heart is an incredibly powerful magical force. Witches, princes, and our hero, Tristan, all chase after it, but for wildly different reasons, and each reason teaches us something about the world.

The witches want it because it will allow them to regain their youth, and watching them chase the star tells us about the magic system. The princes want the heart because their father, the king, promised to give his crown to the prince who could get the star first, and that tells us about the government of this world. Tristan, even though he is from outside this world, wants the star for the sake of proving true love, and that teaches us broadly about the differences between Tristan’s world and this one, as well as the similarities.

3. History

3. History

If power and politics tell us about the flow of power, let’s think about how that power system has actually been working up until now.

- What happened in this world before your story started?

- How does it inform what’s going on in the world right now?

- Why does it matter?

- If you’re trying to save the world, why was the world worth saving in the first place?

- If there is a curse that needs breaking, when and how was the curse cast in the first place, and might that hold the secret to undoing it?

History can offer context for the stakes of your current plot. If it’s important to know the backstory of your character before the story starts, the same might be said for your world.

This is especially helpful with sci-fi that takes place in the future. What is the historical timeline of events between the real-world present and the present tense of the story you’re telling?

In Farenheit 451, for example, the reader is immediately wondering when the world became like this. When and why did people decide that books should be burned? When did that become a law? Ray Bradbury uses some softer worldbuilding tactics here, so we don’t get all the details. But we do have enough context for this to be a believable progression of events from the way our current world works to Guy Montag’s world.

4. Maps

Maps are key to making your story make sense—especially if it’s an epic adventure to the center of the galaxy, or even just to Mordor.

Where is everything?

Even if there isn’t a fancy illustrated map at the beginning of your book (although that is the dream) it’s important for you as the author to have some spatial awareness. Maps are usually more important to writers than they are to readers.

If your character visits a secret library, and they discover it on the opposite side of town from where they live, it might not make the most sense for them to stop by on their way to the bakery… which we know is right next door to the character’s house. If the character leaves from their house, it might make more sense to stop by the bakery first, and then go to the library.

You can think about this on a macro scale or a micro scale.

Many fantasy authors, for example, will chart maps of whole continents. The maps of places like Narnia, Discworld, and Florin and Guilder are beloved by fans of the books those worlds belong to.

This is huge macro level thinking, and a map of the entire world in which your story takes place—even if your characters never get to all of it—can be a helpful way to conceptualize the breadth of your setting. (Plus, there are some pretty neat online tools to help creators with this.)

On a micro level, you could sketch out the interior of the spaceship characters are traveling on, or the village a character lives in.

This level of mapmaking is more applicable across the board. Even if it’s a map of someone’s bedroom that no one ever sees but you, it can be an important tool for spatial awareness in your writing, and more than that, spatial consistency.

5. Language

Your characters will probably be speaking—at least on the page—in whatever language you’re writing in.

But the way they speak versus the way other characters speak can offer a lot of context to different regions, dialects, and in-universe languages. And that, in turn, tells us a lot about culture and cultural relations between groups of people from different parts of your world.

V. E. Schwab is one of many authors to point out that cursing and swearing is an important part of language that authors should consider using to their advantage when worldbuilding.

“The way we curse can tell the reader if there is a god in this society, what they worship, what they fear.” — V. E. Schwab

When we swear, we say things like “go to hell,” but is hell called something else in your world? Do your characters believe in it enough for it to be a threat? Or is there something worse than hell that they’d threaten?

What characters say and how they say it reflects what they believe. Threats and compliments are all relative to how characters see the world around them (and what’s in that world to see).

Even in Harry Potter, when Ron says things like “Merlin’s beard!” it doesn’t necessarily reveal to us the secrets of the afterlife, but it does tell us that Merlin existed in the Harry Potter universe. And it tells us a little bit about how the wizards of today think of and remember him. He’s a legendary figure, but he’s also a source of humor.

6. Religion

6. Religion

Speaking of hell, what is it?

- In your world, is it a version of the Christian hell that we’re used to seeing in Western media?

- Or is it based on something else entirely?

- Does it exist?

- And is there a heaven, or a form of reincarnation?

- Is there one god, or is there a whole pantheon of gods like in Greek and Roman mythology?

- Is there no god at all?

- And separately from what is actually true about your world, what do your characters believe is true?

How characters conceive of their own lives and what might happen to them after they die plays a huge part in how they behave day to day. It can shape their civilization, if it’s a religious state, and it can in turn be shaped by the world itself.

Some Celtic people, for instance, have stories about mountains that are the corpses of fallen giants. What about the physical world in your story affects what your characters believe?

- Octavia Butler, for example, created a religion called Earthseed in Parable of the Sower. It’s based on the idea that God is Change.

- The Earthsea books by Ursula K. Le Guin, for example, take inspiration from Taoist principles, but broadly don’t include much religion in them.

On the other hand, there could be an absence of religion in your world. Maybe your story takes place in the future and your characters have moved past religion as a way of seeing the world.

7. Culture and Folklore

If religion is about what characters believe the world has created for them, then culture and folklore are what characters create in the world for themselves.

Culture, in this context, includes how people live day to day, what they spend their time thinking about. Customs, holidays, and special anniversaries can tell us about the pillars of daily life in a place. Think of Lord of the Rings, when Bilbo is celebrating his eleventy-first birthday—it clues us in to how long hobbits live.

Folklore can include popular stories characters pass on to one another, like bedtime stories for children. Maybe parents tell hyperbolic warnings of why someone shouldn’t go into a scary forest on the edge of town.

And if a scary forest is mentioned, it’s kind of a Chekhov’s gun—you know someone is going to wander into it at some point. It’s part of writing about characters’ beliefs and how they might be confirmed or challenged over the course of the story. What they expect, what surprises them, and why, are all crucial to plot.

Myths and stories characters tell about the world around them can affect the plot. Howl’s Moving Castle by Diana Wynne Jones is a great example of this. There are some truly frightening beliefs about Howl as a terrifying wizard roaming the countryside… and then Sophie Hatter meets him, and he’s very different from what she expected. A lot less scary, a lot more dramatic. That defines the beginning of their relationship, which in turn affects the plot.

8. Magic and Technology

8. Magic and Technology

The possibilities here are endless. Magic and technology are often what authors of genre fiction think of first when they think about worldbuilding, and they can be the most fun parts of worldbuilding. When you’re thinking about magic and technology, you can bend rules liberally:

- Rules of physics

- Rules of time and space

- And anything we believe is possible, in general.

It’s a good idea to define for yourself whether the approach to magic and/or technology in your story is going to be hard or soft. In general, you need to know all the rules—especially if it’s a system you’re making up. You’ve got to know what you’re doing so that the reader feels secure.

As long as you know the rules, and as long as those rules are steadfast and consistent throughout the book so that your reader feels supported, magic and technology can be extremely expressive.

- In Ender’s Game, a story about kids training and completing various simulated war missions in space, the systems of gravity as the characters move through missions and challenges are intricately detailed. It feels intensely vibrant and believable, and this single mechanic of technology gives us a story that is enchanting and memorable.

- The Kingkiller Chronicles by Patrick Rothfuss is a great example of an extremely complex and nearly scientific magic system. It’s a style of hard magic, with at least six different types, all with different rules within them. It’s something the reader can really dig into and explore.

Magic and technology can be an ultimate burst of flavor in your story, and they can also be the wheels that keep the plot moving. They bridge cultural and physical setting to tie your unique world up in a neat, attractive (and incredibly useful) bow.

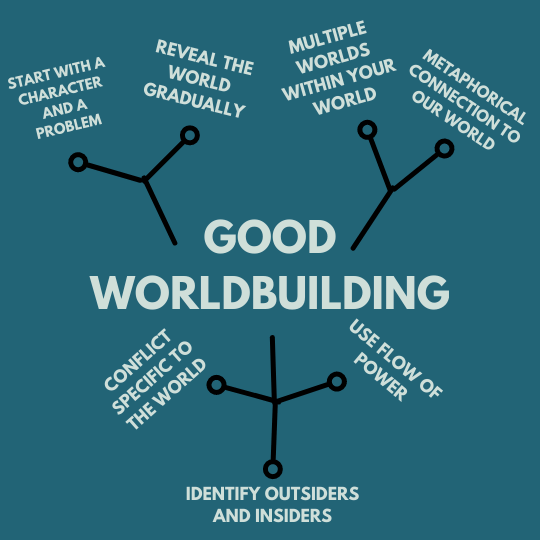

7 Tips for Great Worldbuilding

Now that you have a handle on what you’ll need to do, some questions remain. Namely, how will you do it well?

1. Start with a character and a problem

First things first, keep in mind that a story has a better likelihood of capturing a reader’s attention if it begins with a character, not the setting.

Let’s look at The Chronicles of Narnia: In The Lion, The Witch, and The Wardrobe, the begins with the four Pevensie children. We learn about them as people and the scary situation they’re in in the midst of World War II, sent far from London and far from their mother.

By the time Lucy discovers Narnia in the back of the wardrobe in the professor’s house, we’re already invested in her as a person. Knowing what she must be thinking and feeling about this moment makes it all the more exciting for the reader.

By contrast, young readers sometimes get bored with book one of the Narnia series, The Magician’s Nephew, in which the creation of Narnia is spelled out in great detail. It’s still a beautiful sequence, and we do have characters witnessing Narnia’s creation to be the audience’s guides and points of interest. But comparing the two introductions to Narnia… Lucy’s accidental discovery in the back of the wardrobe is most often referenced and remembered.

2. Reveal world gradually through plot and character description

Brandon Sanderson puts it like this:

- Character first.

- Then, what character wants.

- Finally, their larger place in the world.

This is a learning curve for the reader. It’s important to be deliberate about how long it takes the reader to become an expert in the world. How much do you want to throw at them at once?

This is where you want to be especially conscious of avoiding the info-dump. If you come at the reader too strong with information about the mechanics of your world, it could be harder to grab their attention.

Character and motivation are the most interesting parts of the story. They are the story itself, really, and it’s important to lead with them.

When Dorothy lands in Oz, she doesn’t understand how she got there, and all she wants is to go home. It’s this desire to find her way home that causes her to get help from the munchkins and Glinda, residents of Oz who are directly tied to magical, political, and cultural information about the world. First Dorothy, then what she wants, and then her position in Oz—specifically, the yellow brick road.

Gradually clue the reader in, and trust in your readers to pick things up as they go. It will be a much more rewarding experience all around.

3. Character struggles must be specific to this world

3. Character struggles must be specific to this world

We’ve already talked about how your story’s conflict will be heightened by the world in which it takes place. Your story will be more powerful the more you’re able to intertwine conflict and worldbuilding.

In most cases, worldbuilding will give the conflict context, and as a result, it’ll heighten the meaning and stakes of your plot.

Cultural worldbuilding will also likely play directly into the struggles and conflicts between characters, going back to the idea of systems of power.

A great example of world-specific struggle is Mad Max, in which resource scarcity is the motivating force for every character. They’re all living in a land with hardly any water, and some people (Immortan Joe and his cronies) hold power over it, while others (Max and Furiosa) don’t. The harsh conditions of this futuristic dystopian desert are absolutely necessary for the plot to make any sense at all. That’s part of what makes it so captivating.

4. Metaphorical connection to our world

4. Metaphorical connection to our world

Even when conflict is tied to a world that isn’t our own, a good story still needs an emotional and perhaps situational connection to the experience of your audience.

A story could be really clear with direct allegory and commentary on current politics and events:

- 1984 and Animal Farm by George Orwell are both sci-fi and/or fantastical, and both take place in worlds not quite our own

- 1984 is a futuristic story that’s a critique of contemporary issues like censorship, surveillance, and fascism

- Animal Farm is a direct allegory of the Russian Revolution and a criticism of the real-world political figures involved

Or, it could rely on a much milder emotional connection to something that comes from the characters themselves:

- In Lincoln in the Bardo, the cemetery ghosts are shadows of humanity

- They’re otherworldly and a bit odd because they’ve been dead for so long, but they reflect part of our shared human experience

- They address questions that all readers have about the meaning of one’s life. What happens to us when we die, and where does fulfilment in one’s life come from?

All good art addresses something common about the human experience. Even if your story isn’t about humans, the people who will be reading it are. While elves and Martians are interesting in theory, there should be some heart behind them to really make them meaningful.

5. Multiple worlds within your world

Make your world feel expansive. The bigger it seems like it could be, the more real it’ll feel.

There are the differences in worlds that you’ll likely need for a functioning plot—like the world your main character has known all their life versus the unknown world they enter into as the story picks up speed.

The Shire is a world within itself, but there are so many other worlds beyond the shire, full of elves and dwarves and humans.

But then there are the worlds beyond even what your character experiences. Interplanetary travelers probably won’t visit every single planet in the universe to witness first-hand. So how do we make them feel real enough for the reader to believe in them? To believe that they really could be out there?

As we talked about earlier, this can be a key area to mix hard and soft styles of worldbuilding.

Multiple worlds within your world doesn’t necessarily mean that each of those worlds has to be fleshed out equally or fully within the book. The expansiveness of these other countries or civilizations or planets can be implied.

For example, giving the reader just one small detail, like…

- A particular type of food that is grown only in a certain part of the world, far away, so it’s extra expensive for your characters

- A book discovered in another language that your character can’t read

- Anecdotes told by travelers that have been to places your character hasn’t

- The way other lands or planets look when seen from a distance

- Examples of the way other worlds have affected the politics of this world

… can give the reader a little nugget to wonder about what that faraway place might be like.

6. Identify Outsiders and Insiders

6. Identify Outsiders and Insiders

We see this in life, too, like in school. There are the popular kids, or the “in-crowd,” and then there are the weirdos, the outsiders.

This is another of V. E. Schwab’s favorite concepts of worldbuilding. Some characters will be on the inside while others will be on the outside. This can refer to:

- A literal physical place

- A social or political group

- Those who are or aren’t aligned with a certain cause

Quickly defining who is an outsider and who is an insider for your reader will help with the learning curve of understanding your worldbuilding. Find the central dividing line in your story and figure out who might be on each side of it.

Any story where a character moves from our world into a magical other world is a great example of this. Think of Alice in Wonderland. Alice is an outsider in Wonderland—and so is the reader. Wonderland is intentionally a confusing nonsensical place. Because we get to follow Alice through it, the story is compelling and fun instead of frustrating.

Using outsiders and insiders correctly is key when considering your audience’s perspective. An outsider as a main character can naturally explain things about your world. On the other hand, if your main character is an insider, you’ll need to be a bit more conscious of introducing your reader to the world in a way that feels natural, not forced.

7. Flow of power (political, personal, or magical)

7. Flow of power (political, personal, or magical)

Whether magic or tech based, thinking about power systems will be crucial.

As we talked about earlier, understanding the flow of power in your story will be crucial to constructing your world. And once you understand it as the author, it’s equally important that you communicate this well to the reader—and that you don’t lose their trust at any point.

We want readers to believe in the flow of power so that they’ll root for our characters who are (likely) disrupting it in some way.

It can be helpful to sketch out some systems of power so that you can approach this element of your story with enough detail.

The best example here is probably to think about magic systems.

- Where does the magic come from?

- Who has control of magic, and why?

- Is magic genetic, or is it learned?

- What is the cost of using magic?

The Inheritance Cycle by Christopher Paolini, starting with Eragon, certainly has strengths and weaknesses, but one of its strengths is in its recognition that all magic has a cost, and that cost is amplified and directly built into the plot and stakes of the story. Magic costs a great amount of energy, so a person can only use so much of it at a time. This is part of what makes magical feats impressive. It also means characters can’t run around solving all of their problems with magic whenever they feel like it.

There need to be checks and balances in systems of magic and highly advanced technology. If our characters could accomplish anything they wanted with a snap of their fingers, they’d be able to solve the central conflict of their story far too quickly.

This applies to government and political power, too. Who gets to be in politics, why, and what’s the cost? Same goes for personal power, even. What is it about your world that helps or hinders a character in doing what they want to do?

Establish clear rules and limitations in your discussions of power. Know whether those rules will be broken, and why.

7 Pitfalls of Worldbuilding

Knowing what to do is just as important as knowing what not to do. Because worldbuilding is such a vast project, it’s easy to get off course and make mistakes. Here are some of the most common ones:

1. The info-dump

We’ve probably all read stories that have way too much exposition. We don’t need to know every detail about the history of the town in which our story takes place before we even meet our main character. This won’t grab your reader’s attention. Even if you’ve spent weeks on the history of this place and it’s thoroughly exciting to you that you’ve got newspaper headlines from 20 years before the main events of your story, it won’t be exciting to your readers until you give them a reason to be excited. And a reader’s reason to be excited about the story is in the plot.

Worldbuilding should not replace plot.

It’s a tool to uplift and illuminate your plot, not shadow over it.

Show, don’t tell. This rule applies to pretty much all creative writing, and you’ve likely heard it before. Keep it in mind when worldbuilding. Avoid long-winded exposition about your world before your readers get into it, and instead, gradually lead them in.

Pages and pages of explanation of how a civilization came to be, why a certain holiday is celebrated, or how magic works, without any character action to break it up is, unfortunately, not interesting on its own.

Readers are here for your characters, for the conflict. The world should reveal itself in tandem with these elements of your story, not one after the other.

2. Too much or not enough magic/new technology

2. Too much or not enough magic/new technology

There’s no point in setting your story in another world if it doesn’t tie directly into the story itself.

If it could just as easily take place in modern day, in your hometown, then you can set it there. In a a fantasy world, the fantasy should be an active character in itself, not just a backdrop. If it’s sci-fi, the new technology should be something the characters need, not just want.

All magic or technology should have a specific function in the plot.

The systems of magic and tech are robust and fascinating, and they deserve to be used well. Keep checks and balances in mind, and use magic and technology as a tool to heighten conflict. Your characters should need it to accomplish their goals.

Don’t let it stay in the background for flavor. Bring it to the forefront, where your readers can explore their interest in what you’ve created.

3. Flawed logic or confusion

If you’re inventing a new world, that world probably has some different elements of logic from ours. It’s important to keep them straight.

Even outside of the rules of new magic or technology, it’s important to make sure that things in your world make sense just as much as they do in ours.

If there’s a villain your characters are trying to defeat, make sure the audience understands what it takes to defeat that villain and why.

We’ve probably all experienced a book or movie in which the characters are missing a seemingly obvious solution.

When a story has magic or advanced technology, it can be especially easy to overlook solutions that might be available to your character before you want them to be.

Try to regularly step back and look at your story from a new reader’s perspective. If you can ask yourself, “Why don’t they just…?” without a good answer, that’s a red flag pointing to a loophole in your plot or worldbuilding.

4. Mishandling new races and cultures

Plenty of books in the fantasy and sci-fi canon that participate in perpetuating stereotypes, cultural appropriation, or outright racism. Some were published long enough ago that publishers overlooked or didn’t care, and some are unfortunately still being published.

Dune, for example, is still heralded as one of the greatest sci-fi stories of our time, and it deserves a lot of credit for defining that genre. However, it’s also criticized for being a white nationalist story about a prince who conquers a foreign desert planet and kills billions of the people who lived there.

H.P. Lovecraft has given us so many delightful cryptids and helped define a genre and world of cosmic horror, but white supremacy did find its way into his depictions of other worlds and fantastical creatures.

The good news is that we’re seeing less tolerance for this racism in genre fiction today, although it does still happen. If you spent time on book Twitter around the beginning of 2019, you might remember *Blood Heir* being cancelled before publication for racial insensitivity.

It’s an ongoing conversation, and privileged writers are still learning about how to bring awareness of the conversation into their work.

Be aware, be compassionate, and be inclusive for each member of your audience. Resources for writing characters of color are abundant, and it’s also a good idea to seek out a sensitivity reader if you are writing about characters outside your own lived experience.

5. Time

5. Time

Understanding of geography, distance, and methods of travel can be tricky in a brand new world of your own making.

You don’t want your characters taking a week to walk someplace, and making it back home in just a couple days by the same route. And you don’t want the reader to have to stop and say, hey, wasn’t it Friday like two days ago? How is it already Friday again?

Keeping track of time is important in any story, and understanding time in a world of your own making can be different from understanding time in our world.

You might know how long it takes to drive from Boston to New York from personal experience. But you might not have the same knowledge of how long it would take to ride on horseback up the coast of your imaginary country.

Interplanetary travel, too, is tricky to conceptualize within a timeline. It could help to think about why it can happen quickly in your story. With our current technology it takes seven months just to get to Mars—if your characters are traveling through the galaxy, are they using warp speed, like in Star Wars? Teleportation? How fast can they go?

Time can be difficult to conceptualize if you don’t know the actual distance your characters are traveling. And that’s okay—this is your world, you can make it up! You just have to be consistent.

6. Perspective

Don’t let characters over-explain parts of the world they would already know about for the sake of the reader.

This goes back to the idea of outsiders and insiders. If your main character is an insider, this can cause problems. You have to be very careful not to over-explain the world for the reader’s sake, in a way that the character would already know

Schwab uses the example of an old play, where the plot is conventionally set up by a butler and maid. They have an expositional conversation in front of the audience about things they’re already well aware of, for the sole purpose of cluing the audience in.

If your characters don’t actually need to have a conversation about something with one another, they don’t need to have the conversation with the audience, either. Trust your audience to pick up on context—and make sure you’re delivering the context within your story.

7. Don’t be afraid to leave some things unknown

We don’t know everything about the world we’re currently living in, and that’s part of what keeps life interesting. We hope we have a solid handle on our day-to-day lives, but we still have questions about life and the universe. And that’s okay. Good, even.

The same applies to your story. As long as the reader knows enough by the end of the story to feel satisfied, many authors will leave more about the world up to the reader’s imagination. This could be the author leaving the door open for a sequel, or it could just be a positive side effect of the fullness of the author has delivered.

If a world feels so expansive that a reader feels like they could explore it forever and always find something new, that’s positive. You’ve probably had an experience like this, where you finish a book and feel a sense of sadness that it’s over, wishing you could stay in the pages a little longer. This is what good worldbuilding can do.

It pulls the reader in and gives them a world that they can live in too, alongside the characters, if only in their imagination.

Worldbuilding FAQ

Q: Should I worldbuild even if I don’t like to write an outline before I start writing?

A: Yes. Every story needs a setting, so every story needs a world.

But you can do it differently from how a planner would do it. You don’t need to necessarily have the full parameters of your world figured out ahead of time (because that’s what a planner would do). You can figure it out as you go.

All the elements of worldbuilding we’ve discussed above are important elements to any story. Having an awareness of what worldbuilding includes and what good worldbuilding looks like will help guide your imagination as you discover your story, in the process of writing it.

Q: How much time should I spend on worldbuilding?

A: There’s no right or wrong answer here: spend as much time on worldbuilding as you want. If it brings you joy, feel free to spend as long as you like defining each planet in your galaxy, or your universe, even.

Just keep your goals in mind. If your goal is to finish a novel draft within a year, maybe you should only spend the first month or so worldbuilding. If you’re doing NaNoWriMo or working with a similar time-related goal, maybe spend even less time worldbuilding. And if you’re writing without a deadline, enjoying the process, then feel it out, trust your gut.

Q: Even if the reader doesn’t know everything about my world, do I need to know everything about my world?

A: No. You just need to know what your readers need to know. and maybe a little bit more. You don’t have to know the language the ancient dwarves used to speak 1000 years before the events of your story. If it doesn’t directly connect to the story you’re trying to tell, don’t worry about it.

That said, if you want to come up with that language just for fun, by all means, do it! Building out a rich world could be an opportunity for sequels or spinoff stories, or new stories entirely.

Returning to the idea of the iceberg, even Sanderson acknowledges that it’s okay if you, the author, can’t see the whole of your iceberg. You just have to make your audience think that you can.

Megan Otto is a freelance writer and editor specializing in climate and the arts. Learn more about her writing at megotto.com or find her @megsotto on Twitter.

4 comments

Great post! Many sea explorations are done through submarines, which were invented because someone got inspired by a science-fiction novel.

Regards,

Benoit

This actually helped me alot when i was still fixing the lore of my roblox game

thanks for info

This article on world building is superb (as are a bunch of your other articles). Thanks for sharing your knowledge.