Guest post by Jillian Brenner

Every reader enjoys multi-timeline novels, probably because they are ambitious storylines with energy and scope.

And because most writers have expansive imaginations, they enjoy constructing these multi-piece storylines – but they’re super difficult to write.

Have no fear, since I’m going to show you all the ins and outs of how to write this type of story, and prevent you from wasting years of your life on common mistakes.

WHAT IS A MULTI-TIMELINE NOVEL?

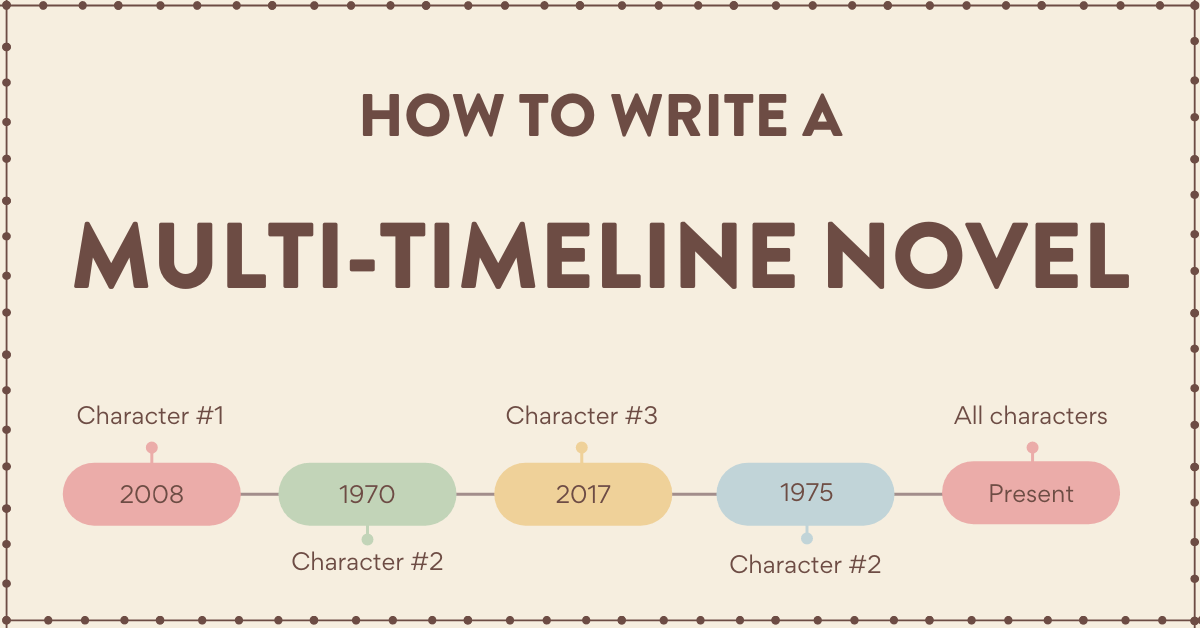

Put simply, a book with multiple timelines means a novel divided into sections set in different times and that immerses the reader in each timeline. These sections can be told linearly or non-linearly.

This piece will focus primarily on non-linear stories told with a “braided narrative,” or sections woven throughout, like chapters, that focus on varying timelines.

Multi-timelines can vary from being set days to centuries or even millennia apart. When deciding if this structure is the best technique for your novel, ask yourself three questions:

- What is my present timeline?

- When are my timelines set?

- How do my timelines connect?

CONNECTING YOUR TIMELINES

The most essential element is deciding what connects your timelines. After all, if your timelines have nothing in common, why include them all in one story in the first place?

Here are 4 ways to tie your timelines together.

1. EVENTS

Emily St. John Mandel’s Station Eleven is an excellent example of structuring timelines around an event; in this case, a devastating pandemic.

St. Mandel John weaves together stories from multiple points of view over roughly three decades. Though the novel’s “present” timeline takes place twenty years after society has collapsed, the book starts well before.

Even from the very first paragraph, St. Mandel John ensures her readers know the central event of the novel:

“Ten minutes before the photograph, Arthur Leander and girl are waiting by the coat check [in Toronto]. This is well before the Georgia Flu. Civilization won’t collapse for another fourteen years.”

By centering timelines around a central event, writers can show the cause and effects for multiple characters and settings. Though the events tend to be negative, such as a natural disaster, devastating accident, death, or otherwise, this is not always the case.

As long as the event fundamentally changes your characters, it can be enough to carry your story.

2. CHARACTERS

Multi-timeline novels often track characters or sets of characters across years.

This can be done by crafting generational epics, following a group of friends at various ages, or even following one character through different times.

The Invisible Life of Addie LaRue by V.C. Schwab unveils the history of the namesake narrator–Addie–by immersing readers in eighteenth-century France and braiding the narrative with Addie in twenty-first-century New York.

As readers learn more about Addie’s life in New York, they understand how she became immortal and how her past choices impact her current stakes.

This technique can very effectively create tension in your narrative. If readers see a past character known to be law-abiding and meek, braided with a timeline where that same character is a hardened prison inmate, readers will want to see how and when that happened.

3. SETTINGS

Things and people aren’t the only things that change: places can, too. After all, New York City looks different now than it did a hundred years ago, as does the Amazon Rainforest, as do coastal cities affected by climate change. By keeping the setting consistent, writers can show how events impact the world around us.

One example of this is Kate Quinn’s The Alice Network. The two central timelines show Western Europe in:

- 1915, before the War

- during World War I

- in 1947, in the aftermath of World War II

The two sections highlight the difference between the two wars, the resulting destruction of both, and the long-term effects on the cities and their inhabitants. In this way, Europe becomes an active character in the story.

4. OBJECTS

While this choice for centering multi-timelines is perhaps the least common of the four listed, it is far from ineffective.

But you have to choose a special object. It has to be:

- a cursed object

- a highly valuable object

- a profoundly philosophical object

This technique is used in Anthony Doerr’s Cloud Cuckoo Land. Though we see groups of characters from five different periods, ranging from fifteenth-century Constantinople to twenty-second-century space, all timelines have one thing in common: the characters find an ancient text that changes their lives.

Using objects to tie stories together allows for incredible creative freedom. As long as the writer can trace how an object passes from one character to another, the narrative can spin in any direction

It is important to note that these techniques often overlap. It is common for writers to use both events and characters to connect their timelines. The narrator in the first timeline of The Alice Network is heavily featured in the second timeline, and multiple characters from all timelines in Station Eleven show up in other timelines. The more ways the different pieces of your novel can tie together, the more cohesive it feels.

Bonus Tip:

One easy way to keep track of the narratives of your timelines is through storyboarding. Write your timeline down in whatever format works best for you. Some writers type up an outline of their events; others use index cards, posters, or even notebooks designed explicitly for storyboarding. Whatever your method, it’s helpful to have a visual spread to help organize thoughts, events, and patterns in your novel.

SIGNALING YOUR TIMELINES

When telling a braided narrative, it is essential to let your readers know both when and where in the novel they are. This goal is easily accomplished with one of these 3 signaling techniques.

1. TIME STAMPS

A great way to signal the narrator, setting, and time to readers is merely by telling them. Kate Quinn structures each chapter of The Alice Network similarly to the following example:

“Chapter Two

EVE

May 1915

London”

By labeling the chapters, readers know exactly who is speaking and in which timeline the characters are. When following one central narrator, such as in The Invisible Life of Addie LaRue, there may be no need to state the narrator’s name.

2. PAGE BREAKS

Page breaks are another efficient way to tell readers they have changed timelines.

Cloud Cuckoo Land follows multiple narrators within the same timelines. Rather than labeling each as seen above, Doerr adds page breaks to further divide his novel and labels sections within those breaks with the narrators’ names. For example, one timeline has two narrators, Zeno and Seymour. Doerr divides those sections with the following:

[Page Break]

THE LAKEPORT PUBLIC LIBRARY

February 20, 2020

4:30 PM

[Page Break]

Zeno (Zeno’s section)

Seymour (Seymour’s section)

[Page Break]

Creating these divides allows readers to follow which characters exist within which timeline more easily. This is important for novels that spread a lot of plot between a large cast of characters.

Unless the timeline is supposed to be a mystery to your reader, making it as simple as possible helps readers seamlessly move between periods.

3. OPENING SENTENCE

If you don’t want to use Time Stamps or Page Breaks, then simply state the time and use the characters name in the opening sentence. St. John Mandel does this in the eight parts of Station Eleven.

Chapter 27 uses this technique with the last sentence of the first paragraph:

“Seven years before the end of the world, Jeevan Chaudhary booked an interview with Arthur Leander.”

Even without explicit labels, this tells the reader exactly when they are and which characters this part will follow.

Bonus Tip:

Some writers may choose to have a timeline that is the “present,” with other timelines taking place in the past or future.

In such cases, the writer might omit the present timeline’s time stamp. Others may combine both page breaks, time stamps, and contextual clues. Just help your reader to easily follow which timeline they’re in.

ENDING YOUR TIMELINES

It can be challenging to know when to end a novel; this is even more true with multi-timeline stories.

Each timeline must come to a resolution, and those resolutions must, in some way, impact or connect with the other timeline endings. If you’re struggling, here are three fantastic tricks to use:

1. INTRODUCE AN ALREADY KNOWN CHARACTER

One oft-used method to ending a timeline is bringing in a character from another timeline.

Perhaps you’re telling a story of a character in his youth interwoven with his later life in which he is married. The older timeline may end with the meeting of your character’s spouse from the present timeline, thus tying them together.

At the end of Station Eleven, multiple characters from multiple timelines come together, revealing that (spoiler!) the dangerous cult leader known as “the Prophet” in the present timeline is actually a grown-up child, Tyler, from a past timeline.

2. CONVERGE

For novels with shorter scopes of time, such as The Alice Network, it is typical to have the timelines converge at the end. Shifting your format may accomplish this.

In the last section of The Alice Network, Quinn drops the timestamps from the chapter headings and moves the timeline entirely into the “present,” or the 1940s. Eve – the narrator from the early timeline – narrates a section in this present timeline.

This shift in format signals to the reader that the older timeline is complete, and Quinn can end both timelines in the present.

3. INTO THE FUTURE

What better to end a timeline than by jumping into the future?

This method works similarly to an epilogue. By going into the future, writers effectively end their previous timeline and flash into a new one, in which whatever obstacles your characters have faced have found some solution.

The Invisible Life of Addie LaRue flashes from its “present” of 2014 all the way to 2016. Though the ending section has only four pages, this time switch offers resolution for readers by showing one journey has ended, and another has begun – though this time, the journey happens off the page.

These are just a few examples of the countless ways to incorporate multiple timelines into your novel. While multi-timeline narratives are challenging, they are extremely rewarding for authors and readers when done well.