Hi, I’m John Fox, and as an editor I’ve helped hundreds of authors write, edit and publish their novels.

If you’re planning on writing a novel, you’ve come to the right place. Let me guide you through the process.

Now, you’re probably intimidated to write a novel. You should be. At least a little. They’re difficult labyrinths and most writers get stuck at the beginning or halfway through and they never finish.

But you can do it. No, it isn’t easy, but it’s not as painful as many would-be authors think.

The trick is to ignore about 90% of the advice out there. Because there’s lots of robot-like corporations and wannabe writers out there dispensing advice, and most of it is washed up and cliche.

I’m going to give you true and honest advice that will be the best you’ve ever gotten — I swear it. This is advice I’ve assembled after editing hundreds of novels and guiding hundreds of authors to award-winning books.

By the time you’ve finished reading this, you will have learned how to:

- Come Up with an Idea

- Figure out the Storyteller

- Select a Starting Point

- Propel your Story

- Develop Your Character

- Create Supporting Characters

- Develop a World

- Advance your Plot

- Bring in the Bigger Picture

- Take the Plunge

- Write a Smash-Bang Climax

- Close out the Story

1. Come up with an Idea

You probably already have an idea for your novel. So my goal is to help you refine that idea so that it will sell lots of copies (you want to sell lots of copies, don’t you?)

Bestsellers are not made through marketing and hiring marketing gurus — bestsellers are born when you come up with a fantastic idea for your book.

A good way to find your idea is to ask the question, “What if?”

- What if dinosaurs were brought to life and put in a zoo, but then they escaped? (Jurassic Park by Michael Crichton)

- What if a missionary was sent to convert aliens to Christianity? (The Book of Strange New Things by Michel Faber)

- What if a black man tried to reinstate slavery and segregation in modern America? (The Sellout by Paul Beatty)

Your book should sound as interesting as those do — it should immediately pique the reader’s interest.

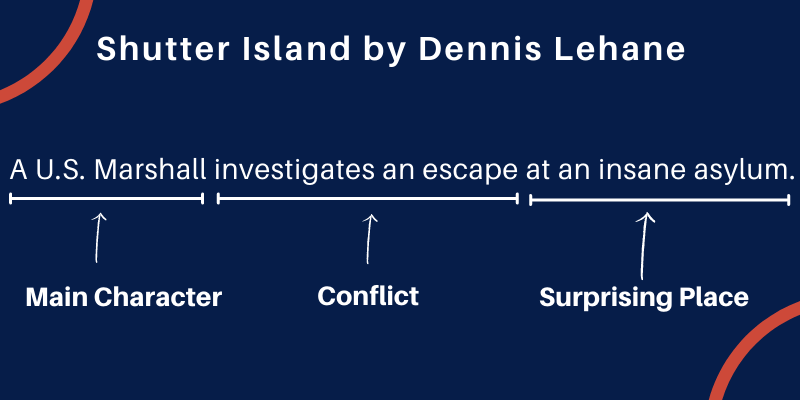

Now you need to take that “What If” and phrase it as a single-sentence statement. It should have several components:

- Main character

- Opposition/Conflict

- Surprising Element

Here’s one from Dennis Lehane’s Shutter Island:

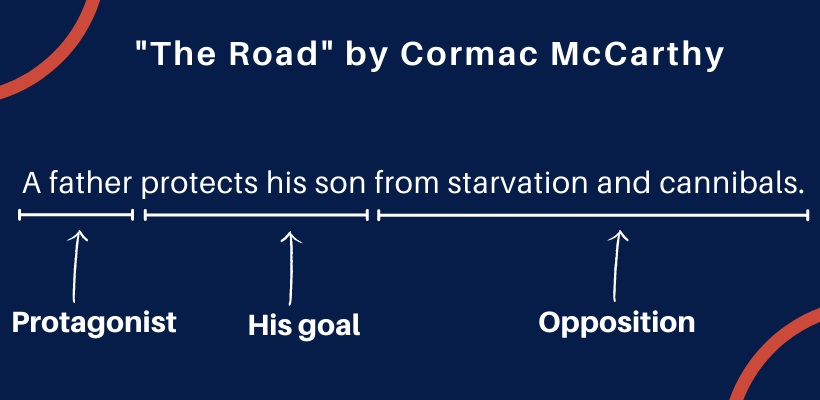

Another way to generate a one-sentence pitch or logline for your book is to use this formula:

The protagonist + their goal + opposition.

This example is from Cormac McCarthy’s “The Road”:

Then try out your one-sentence description on some folks. Do they seem excited or bored?

You want to make them say: “Oooo, I’d read that in a heartbeat.” Then you know you’ve struck gold.

2. Figure out the Storyteller

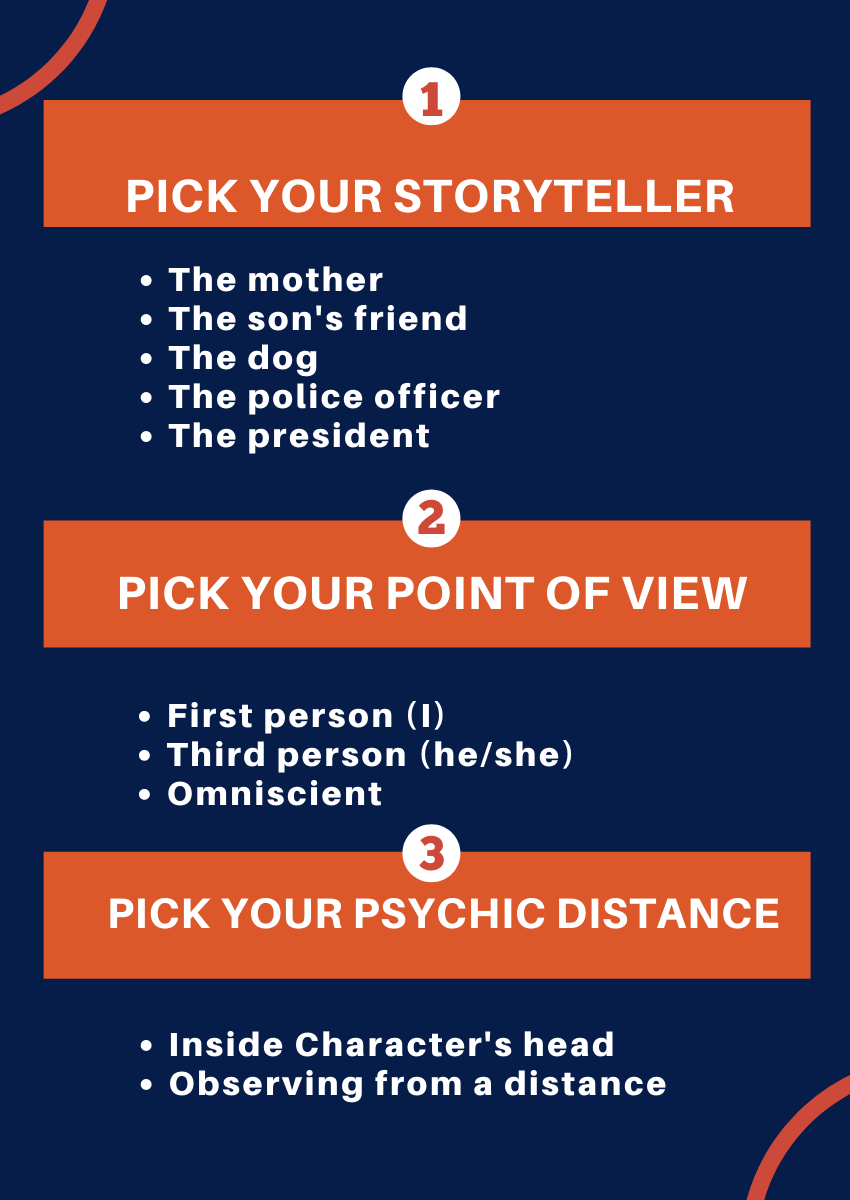

There are three steps to figuring out the right storyteller for your novel.

1. Pick your Storyteller

This isn’t as obvious as it seems.

Sherlock Holmes never got to tell his own tales — Watson was the one who narrated every single mystery.

In “The Lovely Bones” by Alice Sebold, the murdered girl tells the story. Yes, from beyond the grave.

Don’t be afraid to pick someone on the sidelines of your story to tell the story, or someone 30 years after the story is done, or a narrator who isn’t alive. Unusual narrators make for fascinating stories.

2. Pick your Point of View

- First Person — I shot the robber.

- Third Person — She shot the robber.

- Omniscient — The sad orphan shot the robber.

First person is easiest if you don’t want to mess anything up. Just talk about what the storyteller knows.

Third person can be difficult because most writers tend to slip out of the point of view of this character (they accidentally start using omniscient).

And omniscient is great but many writers get flummoxed by the sheer possibility of a trillion story opportunities (it’s awfully complex).

3. Pick your Psychic Distance

This is what most beginning writer’s forget about. How close will the reader be to the storyteller?

- Sometimes readers are right inside their heads, listening to every breath and every thought.

- Sometimes readers are seeing the bird’s eye view of characters’ actions, from far away.

You have to decide how intimate you want the reader to get with your characters.

First person tends to be more intimate, while omniscient tends to be more standoffish, but not always — some writers reverse this.

Pro tip: If you have a disagreeable, unlikable character, don’t get too close in terms of psychic distance. The reader will recoil.

And if you are writing omniscient, make sure to take advantage of that all-knowing eye. Talk about minor characters, talk about characters’ pasts and their histories. Talk about details about the world only an omniscient character would know.

3. Select a Starting Point

Most of the time, writers pick the wrong place to start their book. Even really smart, well-published writers like Jonathan Safran Foer.

It took him months of writing to realize that the beginning of his novel “Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close” wasn’t the right place to start, so he deleted the first 12 pages and started on page 13.

Here are three options to help you pick a place to start your book:

- Start close to the inciting incident (preferably, in media res, meaning in the middle)

- Start with conflict and action

- Start with an event that showcases your character’s personality

Don’t be afraid to flail about and write a chapter to discover the true beginning of your book. You might have to delete that early writing, but remember that writing is a process of discovery. You don’t get it right at the first moment.

I’ve written about starting a novel before, so if you’re stuck, I’d recommend checking out these posts:

In general, try to start as close as you can to the true beginning of your novel, meaning the event that launches the plot.

How Quickly Do Novels Start?

30%

First PageMany start right away

65%

First ChapterMost start quickly

5%

Delayed StartRarely, books start late

What does it mean to “start” your novel? Well, to reveal the central conflict or issue that will propel the storyline.

And from the graphic above, you can see that 95% of the time, that happens in the first chapter (often on the first page).

That means a prologue, which doesn’t involve your main character and doesn’t launch the main storyline, is not as common as most writers think.

4. Propel Your Story

After the first chapter or two, where you should have started your story, now it’s time to accelerate your story into the middle.

Since the beginning of your novel launched the problem, at this point you need your main character to try to solve that problem. Often, this means your character is changing from someone who gets acted upon (passive) into someone who acts on others (active).

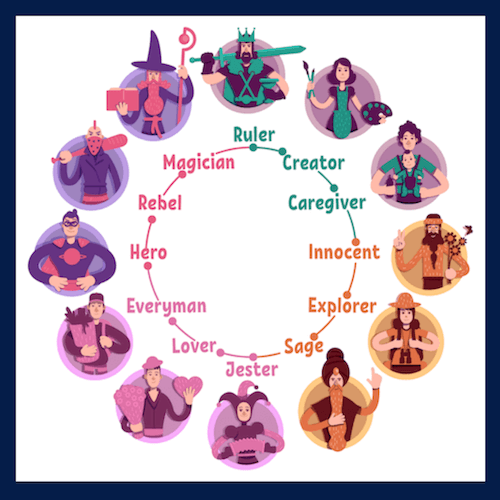

Try using Carl Jung’s character archetypes to clarify this point in the journey:

- In your first chapter, your character is an Orphan (suffered a loss, a tragedy, a problem)

- In your early novel, your character is a Wanderer (trying to find solutions to his problems)

- In your middle novel, your character is a Warrior (fighting for a solution)

3 CHARACTER ARCHETYPES

Orphan

In the 1st Chapter, your orphan has suffered a loss, a tragedy, or has a problem.

Wanderer

In the early novel, your character is a wanderer, trying to find solutions to their problems.

Warrior

In the middle novel, your character is a warrior, fighting for what they want.

So for this early novel, how will your character “wander?” What steps will he or she take to solve the problem of the beginning of your book? Here are some examples of wandering:

- Start a journey

- Make a huge decision and act on that decision

- Try to figure out the solution for a problem

For an example, let’s look at The Martian by Andy Weir, where an astronaut is stranded on Mars (played by Matt Damon in the movie).

In the early novel, this astronaut is wandering by:

- figuring out how to farm

- figuring out how to avoid suffocation

- figuring out how to communicate with earth

5. Develop Your Character

Characters sell books.

Characters ARE books.

You can’t write a book without a character. And no bestseller has characters that are lackluster and forgettable.

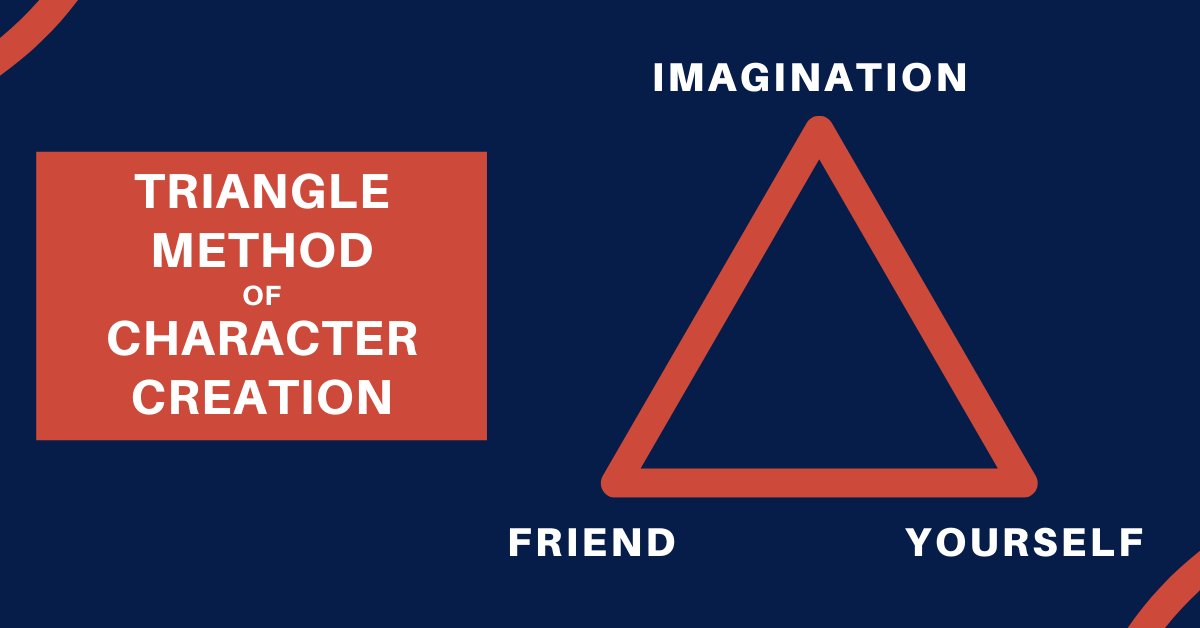

I would suggest coming up with a character by combining three pieces. This is my strategy that I outlined in my “Triangle Method of Character Creation” course. You will take one thing from each category and combine them to create a new, fictional character:

- Friend. I take one personality or physical trait from someone I know. Perhaps they hate heat. Perhaps they are easily insulted.

- Yourself. You should take one element from yourself. Make this the most personal one: perhaps you’ve always hated your mother or your father.

- Imagination. Make one thing up entirely. This is a piece that’s needed to fit your particular story. For instance, the character’s occupation is underwater welder.

Combine all three of those elements and you have a newly minted character, someone who has never existed before. Congrats!

I’ve written at length about developing characters in my article on “12 Steps to Develop a Memorable Character.” Check that out to continue to fuel your character building.

Now that you have a character, it’s time to get to know them a little bit better. Run through this simple exercise and you’ll feel like this character is your new best bud.

Here are five things every author should know about their characters:

- Their Addiction. I’m not only talking about drugs or alcohol. I’m talking about coffee. Video games. A sense of power or control. Feeling like a victim. Sex. Nobody is free of addiction. Every character NEEDS something, they crave something, and once you figure it out, you’ll draw a much more accurate picture of them.

- Their Body. Not just what they look like, but how they dress. What they hate about themselves. What has hurt their body in the past. How they exercise (or don’t exercise). If you know a character’s body, you will know how they live and move and exist in the world. We all live inside bodies — know what your character’s is like.

- Their Social Life. Are they introverts or extroverts? How do they treat authority figures? Do they have lots of friends or few friends? Are they forthcoming with people or do they hide it all inside? What is their relationship with their parents? Knowing how your character reacts to other humans is essential.

- Their Backstory. Every character has something that has happened to them in the past. You must know how those experiences shaped them. Not just traumatic experiences, but also the great memories as well.

- Their Beliefs. Every character thinks something about the world. They have ideas and philosophies. They have political beliefs, and religious beliefs, and economic beliefs. How do these impact who they are and what they do? To have a motivated character, you need a character with strong beliefs.

If you want to develop your character even more, I would recommend using my 4 Questionnaires for Characters, with more than 60 questions and exercises to help you get to know your character better.

6. Create Supporting Characters

No protagonist does it all on their own.

They need characters to help them along the way, characters like:

- a mentor

- a sidekick

- an antagonist

Well, that last one doesn’t help them exactly. But it does help you to tell a much more interesting story!

The point is that you need to do characterization for sidebar characters, so the reader feels intimacy with them.

To develop these characters, you need to figure out three questions:

- How are they different from your main character?

- How do they impact the plot?

- How are they different from each other?

If you want to learn more about supporting characters, I have a whole video and exercise for supporting characters (and how they’re different from minor characters) in my 36-video course, “Write Your Best Novel.”

And of course you need to come up with incredible names that are memorable and very different from each other. Consult my resource on 13 Strategies to Name Your Character to help you with this.

7. Develop a World

If you’re writing sci-fi or fantasy or dystopia, you are literally creating a world out of scratch.

You get to decide the:

- laws

- animals

- government

- culture

And obviously if you’re writing historical fiction, you’re assembling a world through your research.

But even if you’re writing literary or crime or romance, writing in our normal, current world, you’re still doing world building. Every detail you select creates a portrait of what the universe of your book is like.

Even something as trivial as describing breakfast can tell the reader a ton about these characters and this world, as Margaret Atwood notes:

“I like to wonder what people would have for breakfast, and where they would get those food items, and whether or not they would say a prayer over them, and how they would pay for them, and what they would wear during that meal, and, if cooked, how, and what sort of bed they would have arisen from, and what else they might be doing while having the breakfast … Breakfast can take you quite far.”

Part of world creating is choosing surprising, unusual details. And choosing unusual character mannerisms.

You would think that all these small things don’t matter as much as the plot, but you would be wrong. All these little small details that you wedge into your story, alongside the plot and dialogue and character building, they create a texture for your book. They make the reader feel like they’re being transported.

Three quick examples of fun details:

- “Then one of the monkeys caught sight of some life form in the hair of his little girl and reached up and snatched it off her scalp and swallowed it.” (Ann Patchett, State of Wonder)

- “The baggage-claim crowd was like a group of colorful stragglers in front of some third-rate nightclub: sunburns, disco shirts, tiny bejeweled Asian ladies with giant logo sunglasses.” (Donna Tartt, The Goldfinch)

- In a funeral pyre for his mother: “The toes, which were melting in the heat, began to curl up, offering resistance to what was being done to them.” (Aravind Adiga, The White Tiger)

8. Advance your Plot

Okay, so you’ve had your character desires struggle and flail against obstacles and escalated obstacles, but you’re only two-thirds of the way through your book. What do you do now?

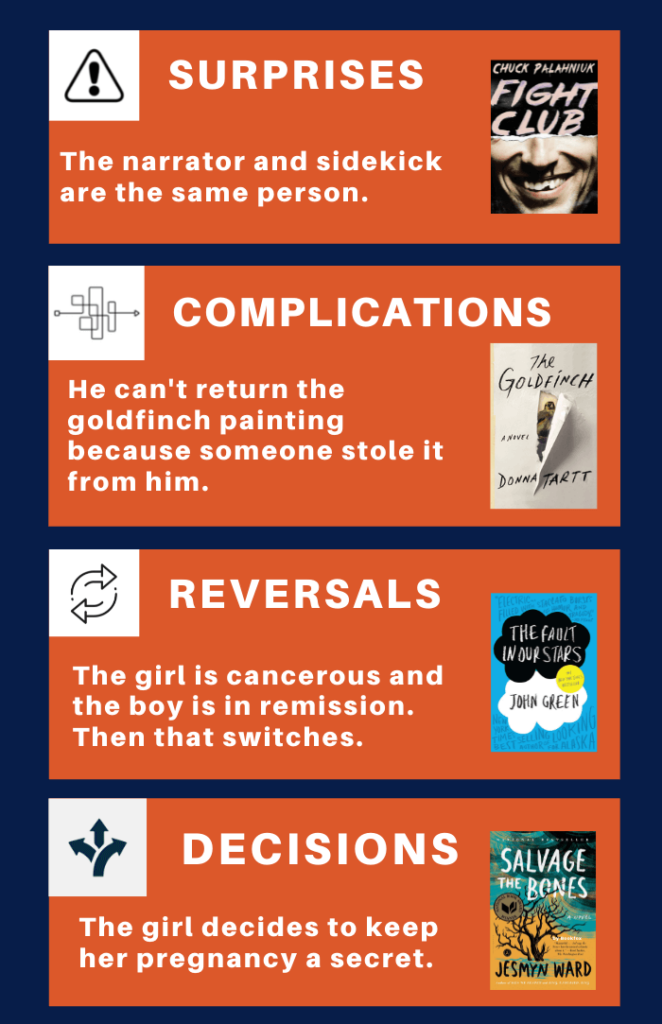

Let me give you four additional techniques that writers often use to throw a wrench in their protagonist’s plans, just before they reach the climax.

- Surprises. Nothing excites a reader more than getting to a huge surprise. And right here, 2/3rds of the way through the book, is the right place for it.

- Examples: Reveal the true identity of the informant — it’s the main character’s son! The bomb is actually in America, not in Afghanistan. He has two wives, not just the one.

- Complications. You always want to make it more difficult on your character to achieve their goal. Throw a few more obstacles in their way at the last moment.

- Examples: The guards came back early. The wife came back early. The baby was born with health problems.

- Reversals. Any kind of betrayal from a friend or ally shocks the reader. You can also reverse the desires of the protagonist, and make them work toward the opposite aim.

- Examples: The Martians who were their allies turn out to be turncoats. At first they wanted to sabotage a gathering of world leaders, and now they want to protect it.

- Decisions. It should be a decision they didn’t want to make. It should be a difficult decision. And this decision has to radically impact the plot. Lastly, this decision has to be surprising, but also make sense for their character development.

- Examples: After decades of being a pacifist, your character decides to kill someone. Your character decides to head behind enemy lines. Your character decides to marry his best friend’s fiance.

The overarching strategy for moving your plot forward is escalation. Every single step of the story should get the reader closer to that climax. Things need to be tougher. They need to seem like failure is right around the corner.

If you get stuck on plotting, look at my 9 story structures — it’s a very helpful resource to help you sketch out the plot of your whole book.

9. Bring in the Bigger Picture

Good stories never exist in a vacuum. You have to connect your book with the conversations that your reader already knows.

Here are three ways to connect your book to the world:

Connect your story to history. Whether you’re writing during the time of 9/11 or the Civil War or a pandemic, books that take place around historical events have weight. Find what is happening in the world during your story and connect your small story to that larger story. Readers instantly connect with your book because they already have an emotional connection to the historical event.

- All The Light We Cannot See by Anthony Doer took place during WWII, and that gives the book gravitas and meaning.

- The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen takes place during the Vietnam War, both in Vietnam and in the United States.

- The Grapes of Wrath by Steinbeck taps into the struggles during the Great Depression.

Connect your story to ideas. What is the bigger picture idea you’re wrestling with in your book? It could be about the price of freedom, the ethics of reproduction, the responsibility to the environment, the struggle between the genders, duty to one’s country, or the difficulty of romance. Make your characters talk directly about these big picture ideas.

- John Green’s The Fault in our Stars talked about the endurance of love in the most difficult of situations (both teens have cancer).

- Patrick DeWitt’s The Sisters Brothers wrestled with the immorality of greed (they find a huge gold deposit).

- Ann Patchett’s “State of Wonder” dealt with the ethics of reproduction (they found a drug that enabled women in their 60s or 70s to have babies).

Connect your story to an argument. Make sure you know what you want to say with this story. In other words, have a point to make. You shouldn’t start your story with an argument in mind, but it will arise naturally as you write the book. Make characters and plot most essential, and layer in your argument as the story unfolds.

- Margaret Atwood’s A Handmaid’s Tale was an argument against patriarchal societies and the imprisonment of women.

- Ernest Hemingway’s Old Man and the Sea was about the perseverance of the human spirit against nature.

- Dave Egger’s The Circle argued that privacy is necessary and good, and social media can be dangerous.

10. Take the Plunge

So many writers make the mistake of being too kind to their protagonist. They never really bring them to their lowest point.

Which is a shame, because readers need that low point — or plunge — to make them feel the tension. Bring your protagonist to the lowest point of despair:

- Make them believe everything is hopeless

- Make them believe they’re worthless

- Make them believe that they’ve failed at their goal

Unless you bring your character to their absolute low point, you will never convince the reader that things might go badly. And so when you have a happy ending, it won’t feel very satisfying, because the reader was never worried.

Ideally, you want the plunge to happen just before the climax, so the contrast is strong.

- Cormac McCarthy’s “The Road”: The father dies just before the boy is rescued.

- Gillian Flynn’s “Sharp Objects”: The daughter is depressed and letting her mother poison her before they solve the murders.

11. Write a Smash-Bang Climax

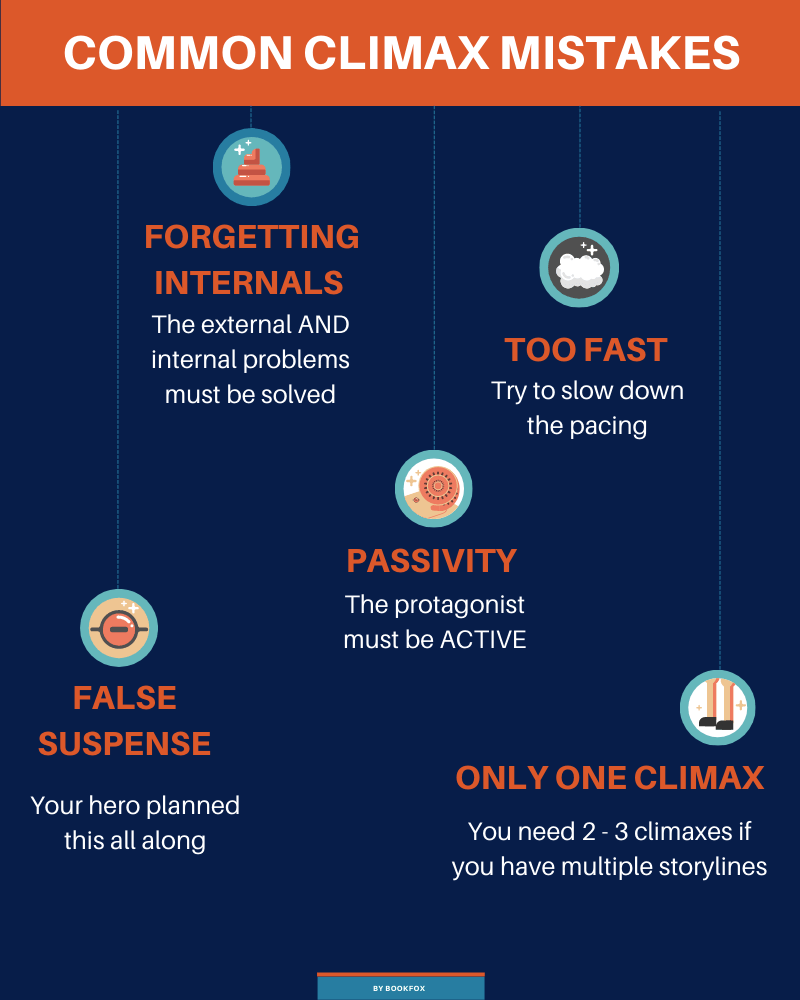

Oh, this part of the book is a boobytrap for writers. It’s easy to trigger all sorts of tripwires and fall into so many spiked pits.

Let me save you some trouble by telling you what a good climax should do:

- Should fulfill the main character’s desires. Whatever the protagonist has been going after for the whole book, this is where you deliver that desire. (or fail to fulfill, if this is a tragedy). If you’re writing a bittersweet book, you can fulfill one of the character’s desires (to the win the girl’s heart) but not other (they lose the championship game). Bittersweet endings are excellent because they make the reader happy and also avoid being cheesy and unrealistic.

- Fulfill the expectations of the genre. But whatever you’re writing – fantasy, YA, romance, literary, crime – know your genre conventions. What is expected of a climax? ]

- There are certain expectations of, say, the romance genre. Most of the time the couple gets together. Sometimes they don’t. But either way, the relationship question has to be resolved.

- Historical: stick with history, but also deliver a surprise between the lines of history. The climax is often a better known historical event. HOW is happens must be a surprise.

- Fantasy must deliver a climax that uses the magic in their world in some way: a climax that’s reliant upon the rules of worldbuilding you’ve done all along in your book.

- For literary works, there’s often a certain amount of subtlety or ambiguity or complexity about the climax.

- Give Every Character a Role to Play. The hero can’t succeed on their own. This is the most common mistake I see in climaxes. For example, in Dune, our main hero Paul is unconscious. And it takes his mother and his girlfriend to help revive him. They have to play detective to figure out why he’s comatose. Only then can he lead everyone in war. Without those two supporting characters, the hero would never have succeeded.

- Resolve all the conflicts. This climax should resolve the main conflict of the book, the internal conflict of the protagonist, and any other loose conflicts (otherwise, you better resolve them right after the climax).

12. Close Out the Story

Once you’re ready to finish up the story, you need to take these three steps at the end:

1. Show Character Change

As you’re trying to wrap up your book, the most important question is: how has your character changed?

Character change is one of the most satisfying elements of storytelling. A character who remains the same is a boring character.

So ask yourself:

- How has this character evolved or shifted over the course of the story?

- What have they learned?

- What will they do differently from now on?

2. Tidy up Plot Strands

If there is a minor or supporting character who has a story, make sure you tell the reader how it ended.

If there are any questions left in the reader’s mind (but what happened to X?) then this is the place to resolve those questions.

The end of a story works like a piece of music — you want to resolve to the tonic chord, so everything seems right with the world. That means you need to provide the answers that the reader has been seeking for the whole book.

3. Highlight your Theme

The most difficult part of a book is knowing how to write the last few paragraphs. Here are three tips:

- End on dialogue. At the end of Walter Tevis’s The Queen’s Gambit, the heroine asks, “Would you like to play chess?” It’s the perfect line of dialogue to wrap up a chess novel.

- End on a thematic note. What is your book about? P.D. James’ The Children of Men is about a world where no one can have babies any more. The human race is dying out. So of course the book ends on the birth of a baby, the first baby in decades.

- End on a departure. Just as the reader is about to say goodbye to the book, have a main character say goodbye. In “A Wrinkle in Time” by Madeleine L’engle, Mrs. Whatsit departs in a gust of wind.

- End on a decision. At the end of Alexander McCall Smith’s #1 Ladies Detective Agency, a man proposes to the main character. And even though she has refused him before, this time she finally says yes.

Here on Bookfox I have a post about how to end your chapters, and many of the ideas are relevant when you’re trying to end your book: 12 Ways to End Your Chapter.

Lastly, I have a post which gives 100 examples of story endings, and which can be very useful in helping you generate possible ideas for ending your book.

How long does it take to write a novel?

Most writers can finish a rough draft in about 6 months. But I’ve seen some writer blaze through a draft in 4 weeks, while others take two or three years.

How long are most novels?

Don’t write a novel more than 100,000 words — it’s tougher to get it published. And if you write something under 70,000 words, it’s too short.

So aim for 70k – 100k words (and never cite page count — writers only use word count).

Can I actually finish a novel?

Yes. Absolutely, you can. I’ve helped hundreds of writers, most of whom had never written a book before, finish their novel. It is possible. All you need is to follow the advice above (and if you want extra help, take my course on how to write a novel).

What if I get Writer’s Block?

Writer’s Block is part of the creative process, and it’s natural and normal. To get past it, I would recommend:

- reading my article on 25 Ways to Defeat Writer’s Block

- watching my YouTube video

- taking my online course, “Master Your Writing Habits.”

Should I self publish or traditionally publish?

So for self-publishing, there’s lots of upsides: there’s no wait time, and you get complete control of the project (such as cover art and illustration), and there’s not that much of a cost if you do it all yourself.

But … you have to do all the marketing yourself, and you don’t have anyone to guide you through the process, and you don’t have the prestige of being published by a traditional publisher. You should do self-publishing if you’re a real go-getter and you think you can get the word out there about your book. (Here are 7 self-publishing success stories).

For traditional publishing, there are also many upsides: you would get an advance (money is nice!), they would handle all the proofreading, ISBN, illustrations, cover art, etc, and they would give you some guidance with how to do the marketing and promotion.

But … it can be very hard to get an acceptance from a publisher. Sometimes you have to send the book out for a year or two, submitting to a hundred outlets or more. Go this route if you have a lot of patience and you want the book to reach a wider audience.

Please comment below with any questions you have and check out my course on “Write Your Best Novel.”

8 comments

Very interesting and informative.

lovely help.

“John Matthew fox” I’ve been reading his articles for months now and I can say, they’ve all been amazing. His articles and post are just the right food a writer needs to move on and complete a story. His not only an awesome author but also a great editor and mentor.

I really appreciate your advice. It made sense and very helpful. Helped me alot with my current book I am writing. Thank you.

Just so you know, a piece of music ends on the tonic, not the dominant. Other than that, thanks for the article.

Wow! I wish I had discovered this advice 30 years ago. But better late than never. I would be thrilled to write my novel at age 70!

What if you have many ideas inside your head? I mean, several universes all at once? And you just can’t decide on a single one? What to do then? How to single out that one idea to work on?

Excellent advice. Wish I had found this when I was writing my novel. It did give me a way to critique my work to make sure that I had followed all of the salient points. What I need now is a traditional publisher who is willing to take a chance on me. . . It should be easier than it is to get published, or at least be given an opportunity to get published! I don’t even know where to begin.