How well do you know your characters?

How well do you know your characters?

You’ve probably asked yourself some form of this question before. Most successful writers spend time delving into the characters who populate their pages.

Countless resources exist (such as Bookfox’s “4 Character Questionnaire Tests—Can You Pass Them?”) to help you create characters rich in backstory, motivation, and personality—just like real people.

But how well do your readers know them?

Even if a character is vivid and dynamic in your head, they can fall flat on the page without thoughtful and varied characterization. In this post, we’ll outline twelve methods for developing your characterizations—and one simple trick for writing characters your readers will never forget.

To write your most dynamic characters, you’ll need more than a memorable detail like Captain Ahab’s whalebone leg, or Anne Shirley’s carrot-red hair. You’ll need all the tools below.

1. Description Builds Character

Never underestimate the power of appearance. A character’s face, body, hair, clothing, and accessories can tell readers a lot about who they are.

Never underestimate the power of appearance. A character’s face, body, hair, clothing, and accessories can tell readers a lot about who they are.

And some research suggests that appearance doesn’t just affect people’s perceptions of us—it might also form our personalities.

Just take this excerpt from R.O. Kwon’s “The Incendiaries”:

I saw the figure at the doorsill, a clean white apron knotted around his waist. I saw him float; I looked again, and it was the filth, a half-inch of skin stained black at his soles, the heels split, flaking….He wasn’t tall, but his shoulder muscles strained against a plain white shirt. His wrist bulged where he’d tied a red string, letting it dig in. With his hair brushed to stand upright, a high plume, I had the sense of a surfeit of energy, not quite contained, like a child’s color-book illustration escaping its lines.

These details aren’t just visual. They speak to his essence. His chapped heels suggest he’s often barefoot, for example. His hair tells us he cares about how he looks.

Beware of the urge to exhaustively catalogue every last detail, or devoting equal attention to every character who walks across the page. Asking readers to focus on too many images at once can overwhelm them, causing them to miss your most precise details.

It’s also important to remember that common details like eye and hair color aren’t that revealing of character. All kinds of people have blue eyes and shoulder-length brown hair, for instance. It doesn’t convey anything about their soul.

2. Select a Character’s Mannerisms

We don’t know people photographically, frozen in time. We know them through their movement — their shoulder slumping, their nail biting, their hair ruffling.

We don’t know people photographically, frozen in time. We know them through their movement — their shoulder slumping, their nail biting, their hair ruffling.

Hercule Poirot, the world’s most famous Belgian detective, is known for his moustache and “little grey cells,” but throughout his stories, Agatha Christie notes how fastidious and particular he is, always wanting things just so.

In “The Mysterious Affair at Styles,” Poirot’s first mystery, Christie describes a moment when the detective is stumped by a clue:

Poirot had walked over to the mantelpiece. He was outwardly calm, but I noticed his hands, which from long force of habit were mechanically straightening the spill vases on the mantel-piece, were shaking violently.

The shaking hands speak to Poirot’s frustration in the moment, while his calm demeanor tells us he has a lot of self-control. His rearranging of the vases suggests a need for order and tidiness, both of which motivate his drive to put criminals in their place.

Think of mannerisms as appearance-in-action. As with appearance, try to avoid adding too many mannerisms just for visual affect. Focus on the small and the specific. One well-placed mention of a character absently rubbing a scar or twisting strands of hair around their finger can tell readers far more than a play-by-play of every motion they make.

And look at this list if you need help with generating character mannerisms.

3. Actions Develop Your Character

By the simplest definition, characters are agents of action. They affect—and are affected by—the events of the plot. What they do and how they do it can be some of the strongest illustrations of their character—even if those actions are small or ultimately inconsequential.

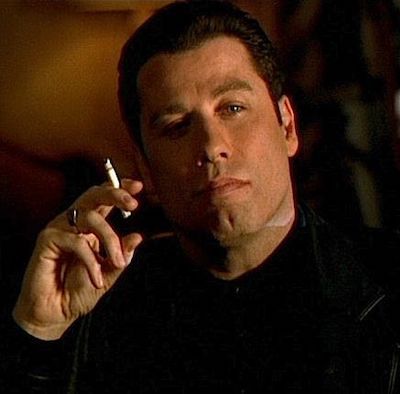

Chili Palmer, the unforgettable protagonist of Elmore Leonard’s “Get Shorty,” is often a man of action. Upon discovering a restaurant coat check has given his leather jacket to loan shark Ray Bones, Chili tracks down Ray’s address and shows up at his door:

He put on his black leather gloves going up the stairs to the third floor, knocked on the door three times, waited, pulling the right-hand glove on tight, and when Ray Bones opened the door Chili nailed him. One punch, not seeing any need to throw the left. He got his coat from a chair in the sitting room, looked at Ray Bones bent over holding his nose and mouth, blood all over his hands, his shirt, and walked out. Didn’t say one word to him.

The fact that he didn’t speak reveals almost more about Chili than the punch itself. But his restraint in only throwing a single punch says a lot too. And why was he punching him? It wasn’t due to life-threatening danger or even mob dealings, but due to a missing coat.

And it’s not just what your characters do that matters — it’s also what they don’t do. If someone starts to kick a puppy and their friend doesn’t stop them, we’ve learned something important about both people involved.

4. Characterization through Reactions

Much of the time, characters aren’t alone. They’re at dinner tables or on buses or just walking down a crowded street. How other characters react to your main character is a rich opportunity for characterization.

This is particularly effective in first-person stories, where narrators might be unreliable.

In Aimee Bender’s short story “Off,” an unnamed narrator is at a party. Her voice is funny and insightful, but from the start, Bender provides hints that there might be something “off” about her. Look at how her ex-boyfriend Adam reacts when she pulls him into a bathroom to kiss:

“Adam, I have a goal to kiss you tonight,” and he says, “C’mon, is that what this is about?” and I tell him to come here but he has his hand on the doorknob but also he’s not gone yet. “You’re incredible,” he says, shaking his head, and I feel mad, what does he mean, it’s not a compliment, and he’s out the door.

Adam’s exasperated response to the narrator’s advances tells readers that she’s hard to handle. It suggests she’s toyed with him before. Like many of us in real life, she lacks the self-awareness or motivation to communicate these aspects of her personality on her own—at least, not as efficiently as Adam can in a few words.

With your characters, take the time to consider each individual relationship from both sides. And then look for opportunities to illustrate those dynamics through their reactions to one another.

5. Dialogue Builds Character

How a character speaks—what they say and how they say it—can go a long way in bringing them to life.

How a character speaks—what they say and how they say it—can go a long way in bringing them to life.

For some writers, dialect is a powerful tool of characterization, but more often (and often more effectively), characterizing through speech means considering word choice and syntax. It’s incorporating appropriate slang and jargon, considering the cliches and common words that pepper their speech. It’s managing the speed and rhythm of how they talk.

Look at this example from a scene toward the beginning of Liane Moriarty’s Nine Perfect Strangers. Husband and wife Ben and Jessica have just arrived at a health resort, where they plan to spend the week:

He opened what looked like a cover letter. “Okay, so this is a ‘guide map’ for our ‘wellness journey.'”

“Ben,” said Jessica, “this isn’t going to work if we don’t—”

“I know, I know, I am taking it seriously. I drove down that road, didn’t I? Didn’t that show my commitment?”

“Oh, please don’t start on the car again.” She felt like crying.

“I only meant—” His mouth twisted. “Forget it.”

In just a few lines of dialogue, we can feel the tension in this marriage. It’s clear that Jessica wanted to come to this resort, not Ben. He’s more skeptical. We also know that they’ve had this conversation before—and they’re both beaten down from the fighting.

Notice also how Moriarty uses punctuation, italics, air quotes, and the placement of dialogue tags to convey tone. For instance, look at Jessica’s first line. Placing the dialogue tag after her husband’s name adds a pause to the pacing, which fits with Jessica’s obvious attempts to remain calm. The dash at the end shows interruption, telling us that Ben has heard all of this before.

Writing Challenge: Not sure if you’re using speech to its fullest potential? Consider asking a friend who knows nothing about your story to read a scene of dialogue without context. Ask them what they can tell about your characters based on how they talk. If their impressions are accurate, you’re on the right track.

6. Backstory as Characterization

Have you ever met someone, formed an opinion about them, and then later adjusted that opinion after learning something about their background?

Have you ever met someone, formed an opinion about them, and then later adjusted that opinion after learning something about their background?

The same thing can happen with characters. Even small, seemingly unimportant details about their backstory can make them much more dynamic.

Danielle Evans’s short story “Happily Ever After” follows Lyssa, a 30-year-old gift shop employee at a replica Titanic/event space. Most of the story sticks to Lyssa’s present-moment challenges, but the opening lines establish her character through backstory:

When Lyssa was seven, her mother took her to see the movie where the mermaid wants legs, and when it ended Lyssa shook her head and squinted at the prince and said, Why would she leave her family for that? which for years contributed to the prevailing belief that she was sentimental or softhearted, when in fact she just knew a bad trade when she saw one. The whole ocean for one man.

Through this one well-chosen anecdote from Lyssa’s childhood, Evans establishes her practicality and skepticism, traits she continues to exhibit as an adult.

It’s worth noting that the backstory doesn’t continue after this excerpt. Over the next few sentences, Evans transitions to Lyssa in the present day. Often when we think of backstory, we picture long and detailed trips into a character’s history. Most of the time, you’d be surprised how much characterization you can achieve with a single precise detail.

7. Highlight Characters’ Thoughts

A recent article from The Independent confirms what fiction writers and readers have long known: we feel closer to people who confide in us.

A recent article from The Independent confirms what fiction writers and readers have long known: we feel closer to people who confide in us.

Fiction works better than movies when it provides what movies can’t — access to other people’s innermost thoughts, without the barriers of etiquette or image management. Exploration of a character’s internal life works like a secret shared with readers, drawing them closer to the people on the page.

Of course, giving readers access to all your characters’ thoughts is a recipe for chaos and tedium, but dipping into those thoughts—particularly when they contradict their actions or speech—can have a profound effect.

Just look at this example from George Singleton’s short story “Perfect Attendance”:

Madison Kent said, “Lemonade,” when the woman asked what she could “hook him up with.” He thought at first, You can hook me up with a grammar textbook, and I’ll show you how come you’re not supposed to end questions with prepositions, but he decided against it.

These two sentences provide a contrast between what Kent says and what he thinks. Readers get a glimpse of the real Kent here, not just how he acts in public.

As with the other characterization methods, be careful not to overuse internal thought without a specific effect in mind. If you want readers to find your character tiresome or you want to emphasize their shyness or duplicity, go crazy.

8. Give Characters a Desire

No character lacks desire. Well, maybe some perfect Buddhist character might, but in general, the stronger a character’s desire, the more memorable they will be.

Think of any character and you will instantly know what they want above all else.

- Frodo wants to destroy the ring.

- Jane Eyre wants freedom and community.

- Elizabeth Bennet wants to marry for love.

You can have a character who doesn’t know what they want, as long as the reader can sense what they want. Ultimately, what a character wants not only drives the plot engine of your story, it also helps the reader to connect with your character.

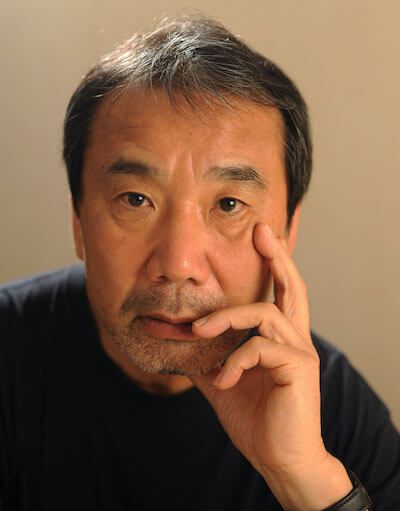

In this excerpt from Haruki Murakami’s “On Seeing the 100% Perfect Girl,” it’s very clear what the character wants:

One beautiful April morning, on a narrow side street in Tokyo’s fashionable Harujuku neighborhood, I walked past the 100% perfect girl … I know from fifty yards away: She’s the 100% perfect girl for me. The moment I see her, there’s a rumbling in my chest, and my mouth is as dry as a desert.

Murakami begins his story with desire. He doesn’t start with describing the character, or telling us the character’s name, or dialogue, but with what the character wants, and that desire helps us understand him better than almost anything else.

And his desire isn’t explicit: I wanted a girlfriend. It’s created through the description of his desire (100% perfect) and the physical sensations of nervousness.

9. Names Reveal Character

Writers have a long history of naming characters in symbolic or literal ways:

Writers have a long history of naming characters in symbolic or literal ways:

- Manley Pointer, Flannery O’Connor’s lecherous Bible salesman in “Good Country People”

- Holly Golightly, Truman Capote’s character of a woman hiding a difficult past beneath her party-girl exterior.

- Dim from Clockwork Orange. I’ll let you guess how smart he is.

- Murdstone, Charles Dicken’s character who is an abusive stepfather (only an -er short of “murder.”)

- Luna Lovegood, from J.K. Rowling. Luna lets you know she’s wacky, Lovegood lets you know she’s sweet.

But even names that hold no deeper meaning can contribute to readers’ perceptions of a character. Jack Reacher would likely be far less compelling if named Mortimer Humperdinck, just as Ignatius J. Reilly would be a different person with a name like Bob Smith.

For this method, baby naming books and websites can be immensely helpful. Skim the lists until you find a name that sounds like your character or evokes the tone you want to convey.

And check out Bookfox’s post on how to name your character, which includes advice about using one-word names and choosing names that are puns.

10. Objects as Characterization

Peek inside your character’s backpack. What’s in there?

Peek inside your character’s backpack. What’s in there?

Take a look at their bedside table or glove compartment. What do you find?

All characters have possessions—even if only the clothes they’re wearing. Those objects can reveal information we might not learn any other way.

Take this example from Tim O’Brien’s “The Things They Carried,” a master class in objects as characterization. In it, O’Brien characterizes a squad of American soldiers in Vietnam:

Mitchell Sanders, the RTO, carried condoms. Norman Bowker carried a diary. Rat Kiley carried comic books. Kiowa, a devout Baptist, carried an illustrated New Testament that had been presented to him by his father, who taught Sunday school in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. As a hedge against bad times, however, Kiowa also carried his grandmother’s distrust of the white man, his grandfather’s old hunting hatchet.

The items these soldiers carry help to reveal and distinguish their characters. Anything these men have, they have to carry on their backs. So a man who makes room for condoms is, in a fundamental way, different from one who carries a hatchet.

As with the other methods on this list, specificity is key when choosing objects. An alarm clock on the bedside table may not tell us much about a character, but if it’s a Bart Simpson talking alarm clock, it sure does.

11. Setting as Character

Time period and place matter. Setting influences a story’s action, establishes the stakes, and conveys tone. For example, a legal thriller set in present-day Seattle will be an entirely different story from one set in Alabama after the Civil War.

Used well, setting can also reveal character. Consider the location and time period of your story. How does your character feel about that place? Are they at home in the world that surrounds them, like Huckleberry Finn on the Mississippi River, or do they feel like they don’t really belong, like Katniss Everdeen in the Capitol?

And it’s not just the general setting that matters. The individual places they visit—the dive bars, courthouses, swanky parties—can also reveal their character. Where are they most at ease? Where do they go most often? Where do people know them by name?

In Celeste Ng’s Little Fires Everywhere, recently made into an Hulu series, Pearl and her mother have lived simple nomadic lives before moving to Shaker Heights. She quickly befriends Moody, one of her high school classmates, and one afternoon, he invites her to his house. Notice how much we can learn about Pearl through her reactions to seeing the house for the first time:

“You live here?” It wasn’t the size—true, it was large, but so was every house on the street, and in just three weeks in Shaker she’d seen even larger. No: it was the greenness of the lawn, the sharp lines of white mortar between the bricks, the rustle of the maple leaves in the breeze, the very breeze itself. It was the soft smells of detergent and cooking and grass that mingled in the entryway….It was as if instead of entering a house she was entering the idea of a house, some archetype brought to life before her.

Pearl’s observations are specific: She notices the brick mortar and the scent of detergent. If these details were part of Pearl’s daily life before this point, she likely wouldn’t notice them. Since they feel like fantasies to her, that speaks volumes about her life.

12. Narrator Characterization

Your narrator provides a great opportunity for characterization of other characters. They stand a step away from your characters but close enough to observe.

Your narrator provides a great opportunity for characterization of other characters. They stand a step away from your characters but close enough to observe.

Many writers forget that Watson is the narrator of the Sherlock Holmes stories, not Sherlock Holmes. Watson’s distance allowed him to gaze at Sherlock, and give the reader a full account of the man and his methods.

But even if your narrator is distant or objective in voice, they can still help to reveal your characters through how they tell the story. If you describe a character as inquisitive, for instance, readers get a far different picture of them than if you called them meddlesome, though both words can be synonyms of curious.

Shirley Jackson uses third-person objective for her short story “The Lottery,” but she’s still able to use that voice for characterization, such as in this example:

The lottery was conducted—as were the square dances, the teen-age club, the Halloween program—by Mr. Summers, who had time and energy to devote to civic activities. He was a round-faced, jovial man and he ran the coal business, and people were sorry for him, because he had no children and his wife was a scold.

If Jackson had described Mr. Summers as content or carefree, instead of jovial, he might read differently, though these three words could be synonyms. The same is true of Mrs. Summers, who could have been called a complainer or critic, with far different connotations than a scold.

The precise words your narrator uses can make a big difference in how your characters are perceived.

Unforgettable Characterizations

If you liked this post and wanted to learn more about characterization, check out Bookfox’s “Character Development Jetpack: 6 Tricks and 9 Questions.”

If you liked this post and wanted to learn more about characterization, check out Bookfox’s “Character Development Jetpack: 6 Tricks and 9 Questions.”

Depending on the length of your story, you might not have the space or need to use all eight methods for every character. That’s okay. The point isn’t to create a mandatory checklist. Instead, taking the time to consider all the tools at your disposal will help you choose the right one for any job.

For the characters that matter most, push yourself to diversify your characterizations.

- If you tend to rely on appearance or speech, sprinkle in some backstory.

- If your character is all action, give them the mannerism of a nervous habit

- If your character offers lots of thoughts, balance it with some dialogue

To build the most memorable and dynamic characters possible, look for contradiction among the methods.

- If your protagonist has face tattoos and rides a Harley, they should be offended by profanity and bad manners.

- If she’s a kindly old grandma who knits and bakes cookies, include backstory from that summer she worked on an oil rig.

- If he’s a high-powered corporate raider with a Ferrari and expensive Italian suits, let him sleep with a tattered old teddy bear.

Being intentional with contradiction ensures your characters won’t become stereotypes. They’ll be distinctly themselves instead—and that’s why your readers will love them.