While science fiction is often set in the future, historical fiction is set in the distant past.

While science fiction is often set in the future, historical fiction is set in the distant past.

Just like sci-fi, historical fiction authors must develop genre-specific techniques to create stories set in a different time period.

In this post you’ll learn how to research historical fiction, create believable characters, create authentic settings, and avoid common mistakes.

What counts as Historical Fiction?

There is no strict definition of what qualifies a setting as the distant past, but these guidelines are common:

- More than 60 years ago. Because one of the first historical novels, Waverley by Sir Walter Scott, was subtitled ‘Tis Sixty Years Since.

- Before the memory of the author. It will also be before the memory of most readers.

On the closer end of the scale are novels like Jennifer Egan’s Manhattan Beach, which is set in the Brooklyn Navy Yard during World War II. As Egan’s novel was written seven decades after the war’s end, few of her readers have experienced the world she wrote about directly.

Other novels—like Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose, which is set in a 14th-century Italian abbey—are far more distant from any reader’s experience.

Historical novels have a huge advantage over nonfiction history books. They can get much closer to the culture and characters than history books, and explore the interior experiences of people living through different time periods.

The Main Mistake of Historical Novels

If we aren’t careful our research can overwhelm our fiction.

An author doesn’t write a historical novel unless they are excited about their period. Naturally, they want to include every interesting and noteworthy detail they have discovered into their work-in-progress.

However, the goals of a historical novel are the same as the goals of any novel: to write a story that entertains readers. Don’t let historical research get in the way of your story. Instead, your research should support your construction of story elements such as character, setting, and plot.

Getting Started

Writing a historical novel is a big undertaking. There are some preliminary activities you can do before you dive into a draft.

1. Do Your Research

If you aren’t going to pack your manuscript with researched details, you can skimp on the research process, right? Not so fast.

Research is crucial for many reasons, beyond merely gathering facts and details:

- Accuracy. While you won’t include every possible detail into your historical novel, you want to make sure the ones you do include are accurate. Details that are inaccurate or anachronistic will undermine the credibility of your project.

- Inspiration. Interesting historical stories tend to be inspired by particular historical incidents, rather than generic situations. History is full of weird stories. Use this material.

- Context. Plots don’t occur in vacuums. Even if your story focuses on a small group of characters, it is important for you as an author to be aware of the broader social and political context of the time.

- Respect. The past is very meaningful to people’s identities. If you are writing about a culture or region you are not directly connected to, make sure you have put in the work to understand the relevant history and its lasting effects.

How to Conduct Research

Secondary sources help you get a broader view of a time period.

History books, biographies, documentary films, and podcasts are all useful resources for understanding a period. Specialized books about topics such as transportation, fashion, mechanics, or agriculture often yield the most surprising information.

Primary sources offer a window into your time period.

Newspapers show you how historical events were seen as they were still unfolding. Other print sources, such as pamphlets and popular books, can help you understand the culture and beliefs of your time period.

Letters, diaries, and memoirs are great for developing characters. These personal sources help you get a sense of what people’s individual, day-to-day experiences were like.

When she was writing Manhattan Beach, Jennifer Egan read a collection of letters at the Brooklyn Historical Society that a woman sent to her husband while she was working in the Brooklyn Navy Yard in 1944.

Take lots of notes as you read. Down the line, you will want to be able to find the information you gathered.

Reference management software like Zotero can be useful, though some people prefer to take notes by hand. Either way, make sure you have a system for saving and organizing your notes.

2. Prewriting

Exploratory writing exercises help you get a better grasp on your project before you commit to a structure.

Draft Working Documents

You will need to keep a lot of information straight as you work. Working documents will help you with organization and continuity as your project develops.

- Timelines. Creating physical timelines allows you to visualize time in space. Draw out parallel timelines of:

A.) Major political and social events in your time period.

B.) Major events in your primary characters’ lives.

C.) Major plot points in your story.

Color-coding these separate timelines will keep them from getting too confusing. Seeing these timelines side by side can help you understand the causal relationships and motivations within your book. This also helps with continuity as your projects grow.

- Maps. Figure out exactly where all the locations in your book were. You need to know where political borders were drawn at the time your story is set, what transportation networks existed between places, and how long it would take for people and messages to reach their destination. Visualizing this sort of information will help you construct your plot.

- Character Sketches. Once you have an initial sense of who your characters are, write out biographical character sketches (in first or third person). Include everything you know about them—physical characteristics, backstory, personality, etc.—based on both research and imagination.

Use Historical Writing Prompts

Genre specific prompts are a way to start getting words down on the page.

Low-stakes prompts are especially helpful if you are feeling intimidated by the scale of your project.

If you aren’t haven’t zeroed in on your historical period or subject yet, more general historical fiction prompts can help you find a story you are excited about.

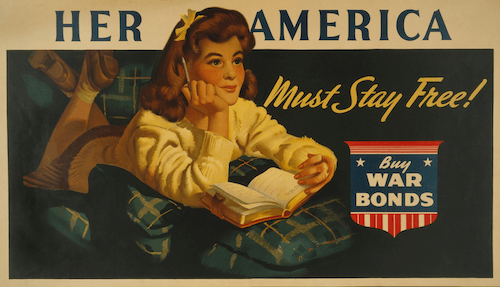

Ekphrasis

Ekphrasis is written reflection on a visual work of art. You can get yourself writing by sitting in front of an image and describing what you see in the frame, what might beyond the frame, and any other thoughts that arise while looking at the image before the buzzer rings.

This method is particularly useful for historical fiction, because a painting or photograph gives you an opportunity to see what the character, setting, or event you are writing about would have looked like.

For stories set long before the print era, visual art works might be your best primary sources. If you are writing about ancient Egypt, for example, you might want to some ekphrastic writing about tomb wall art from the Met’s collections.

When you encounter interesting historical images in the course of your research, save them for ekphrastic writing sessions. You can also search the many collections of historical images hosted online by museums and research libraries.

Ask yourself “What if?”

Research discoveries can be turned into prompts. Toni Morrison began writing her novel Beloved when she found a newspaper clipping from the 1850s about a formerly-enslaved woman named Margaret Garner.

Morrison used the questions “What if?” and “What must it have been like?” to move from research to fiction.

Ask yourself these two questions about archival sources you find in the course of your research.

3. Characterization in Historical Fiction

Famous Figures vs. Invented Characters

You have an important choice when creating characters in historical fiction:

- Write about real historical figures. Look at Raymond Carver’s short story “Errand,” about the death of Carver’s literary idol, Anton Chekhov. Carver’s goal was to write his way into the grace-filled events of his hero’s last moments on earth.

- Construct original fictional characters. The critic Georg Lukács wrote of the importance of the “middle-of-the-road hero” in historical fiction. He believed that the average people of a particular time period can best capture the experience of that time. These are not the type of people generally found in history books. They are, however, the type of people who can show us how most people lived in a particular historical era.

What are the advantages to each?

Well-known historical figures provide you with a lot of material to work with. Primary sources like letters and diaries can give you with a sense of how your subject spoke and behaved. Carver draws on a wide variety of period sources in “Errand,” including the journals of Tolstoy and of Chekhov’s sister. Paintings, statues, and—depending how recent your period is—photographs and even videos can show you what your subject looked like.

But you are limited by the historical material. If you write a Civil War novel focused on Lincoln’s life, you will be constrained to these biographical facts. However, if you write a Civil War novel focused on an imagined Union officer, you will have much greater freedom to construct character and backstory, within the historical framework of the war.

Choosing Between Famous and Invented Characters

You should write famous characters if you want your book to have the allure of real history.

For example, in Deadwood, Pete Dexter focuses on real-life 19th-century Wild West figures such as Calamity Jane, Charley Utter, and Wild Bill Hickock. In doing so, he was able to draw on the many historical print sources about Deadwood’s famous inhabitants. Dexter’s close portraits of these figures are fascinating to anyone with an interest in their lives.

Downside: Your book must compete with countless portrayals of these same characters in history books, dime novels, and movies.

You should invent new characters if you want absolute freedom to explore a time period.

For example, in Lonesome Dove, Larry McMurtry focuses primarily on a more “middle-of-the-road” cast of cowboys and former Texas Rangers. The book (and its sequels) allows the reader to experience the Cattle Drive era through the details of these men’s labor and conflicts. Without the weight of biography, McMurtry was free to focus on constructing characters with backstories and motivations his readers could understand and connect with.

Downside: It’s tougher to write characterization from scratch, rather than starting with a flesh-and-blood person.

You can also choose a mix of both.

Many works of historical fiction will contain some mix of actual, invented, and composite characters. Historical figures, like the famous rancher Charlie Goodnight, show up occasionally in the Lonesome Dove series, but they are generally secondary characters. You have to decide who will be your primary characters.

How to Describe Historical Characters

Simply reporting a catalogue of historical details is not enough to construct round characters.

Paragraphs of static description of a character’s clothing and possessions may establish period authenticity, but they can make a reader feel as if they are sitting through a lecture. A few well-chosen physical details are often plenty for a reader to form a mental image of a character. These details can often be conveyed in action.

In Deadwood, the reader first meets Calamity Jane the day after she arrives in town:

“She stood up and tucked her shirt into her pants. She strapped her gun belt around her waist, and then slid it to the left until the buckle was in back and the pistol lay at an angle across her lower stomach. She thought it fit her, to wear her protection over her womanhood. She tied a wide yellow scarf around her neck and pulled her hat down right to her ears. The hat was perfectly round. She thought it softened her face.”

Dexter chooses physical details drawn from real photographs of Jane: the scarf, the hat, the pair of men’s pants. Dexter could go further in describing the particular type of pants or shirt she’s wearing, or adding other items visible in portraits such as boots or a buckskin jacket, but it would hurt the story.

Instead, Dexter portrays Jane’s feelings about herself.

- Jane connects violence to her gender (the gun over her “womanhood”).

- The hat makes her look better (it softens her face).

Dexter has taken historical details and linked them to character thoughts, beliefs, and motivations.

Ask What Choices your Characters Face

Historical characters are not different from contemporary characters because of superficial things like the clothes they wear or the food they eat.

They are different because of the social conditions they exist in. These conditions set-up specific choices. Choices create plot.

The narrator of Ha Jin’s novel War Trash, Yu Yuan, is an officer-in-training at a Chinese military academy when the Communists take power in 1949. Jin pays little attention to physical details such as military uniforms or weaponry. Instead, he focuses on how Yu adapts to the new political system.

Yu ends up in an American prisoner of war camp in Korea. Caught on the front lines of the Cold War, he is given a choice between being returned to the People’s Republic of China or being sent to Taiwan. Yu wrestles with his decision:

“I wanted to go home. Yet home seemed ominous now—I was unsure what would happen to me if I went back. If only there were a third choice so that I could disentangle myself from the fracas between the Communists and the Nationalists.”

This choice—which arises out of the political conditions of the novel’s setting—becomes the turning point of the novel.

Consider what decisions your characters would face in their life. Taking into account their options, motivations, knowledge, and beliefs, ask yourself what choices they would make.

4. Building Historical Settings

Use Your Characters to Explore Your Settings

Authors often prioritize the construction of historical setting, treating characters and plot as afterthoughts. This approach is backward.

Your story will be driven by your characters. Once you know who they are and what their goals are, you can use them to explore their world.

Bring Characters to New Places

Whenever your plot takes your characters to a location that is new to them, you have an opportunity for them to explore and describe their surroundings.

The Name of the Rose is narrated by a young novice monk named Adso of Melk who is traveling outside his native German region for the first time. Adso is naturally excited when he lays eyes on the abbey where most of the book takes place:

“While we toiled up the steep path that wound around the mountain, I saw the abbey. I was amazed, not by the walls that girded it on every side, similar to others to be seen in all the Christian world, but by the bulk of what I later learned was the Aedificium.”

This moment creates an opening for Eco to give the reader with a detailed description of the abbey. Because the description is part of Adso’s own process of discovery, the expositional material doesn’t slow the novel down.

Take advantage of opportunities to deliver description in-scene.

This will help you avoid stand-alone stretches of description which take the reader out of the story’s action.

Observe Characters’ Interactions with their Settings

A character’s interactions with the objects in their environment can help develop both characterization and setting at the same time.

Adso observes the actions of his master, Friar William of Baskerville in the abbey:

“During our period at the abbey his hands were always covered with the dust of books, the gold of still-fresh illumination, or with yellowish substances he touched in Severinus’s infirmary. He seemed unable to think save with his hands…”

This is effective characterization of Baskerville, as the reader sees the tactile, empirical behavior that allows him to discover clues and move the plot forward.

Just as importantly, the characterization contributes to setting. We see period-appropriate details of manuscript and medicine production, which helps us understand life in the Medieval abbey.

Writing Exercise: Make a list of period-specific objects your characters might encounter. A historical setting (especially a pre-industrial setting) will contain a different inventory of objects than our 21st-century world. Write a scene where your character interacts with objects from your list using at least two of their five senses.

Stick to Relevant Details

As with characterization, too many details about your setting will overwhelm and bore the reader. It is more effective to select the key details that will help your reader envision a full scene in their mind.

As with characterization, too many details about your setting will overwhelm and bore the reader. It is more effective to select the key details that will help your reader envision a full scene in their mind.

To accomplish this, focus on details of setting that are immediately relevant to the action of a scene.

The opening paragraph of Lonesome Dove helps establish the setting of the Hat Creek cattle ranch in Texas:

“When Augustus came out on the porch the blue pigs were eating a rattlesnake—not a very big one. It had probably just been crawling around looking for shade when it ran into the pigs. They were having a fine tug-of-war with it, and its rattling days were over.”

From these first sentences, the reader has a strong sense of the type of place Hat Creek is. The fact that pigs are eating a rattlesnake on a porch tells us more about life on the ranch than the architectural details of the porch or the building.

Prioritize writing scenes, not settings. Build out the setting just as much as you need to to make the scene work.

Focus on What Hasn’t Changed

Places change over time, but they usually don’t change entirely. Some details of the contemporary world you live in can be included in your historical place descriptions.

Natural landscape features such as mountains generally remain the same over the centuries.

The Lonesome Dove cowboys size up the looming Rocky Mountain range that they will have to cross. Despite all the development the American west has experienced over the past 150 years, the “The great line of the Rockies” still looks the same.

Some aspects of the built environment also remain consistent over decades and centuries. Jennifer Egan had to rely on research to construct the inner-workings of the WWII-era Brooklyn Navy Yard in Manhattan Beach. However, no historical research is needed to describe the geography of Brooklyn.

In the novel’s opening paragraph, the main character recalls a trip in pre-war Southern Brooklyn with her father:

“the ride had distracted her, sailing along Ocean Parkway as if they were headed for Coney Island, although it was four days past Christmas and impossibly cold for the beach.”

Ocean Parkway is still the best arterial street to take if you are driving down to Coney Island. It is still too cold to swim in New York in December.

The only thing Egan does to make this scene period-authentic is to specify that the characters are riding in a Duesenberg Model J car. Mixing observed details with key researched details helps sell the researched pieces as first-hand observations.

5. Choose Your Narrator

You need to decide who is telling your story. The POV you choose will affect how you use historical language.

First-Person Narrators

If your historical novel is written in the first person, you will have to develop a historically-authentic voice.

If your historical novel is written in the first person, you will have to develop a historically-authentic voice.

This is a time when primary sources come in handy. Noting phrases, diction, and vocabulary from sources like letters and journals will provide language for you to use as you construct your narrative voice.

Peter Carrey’s novel True Story of the Kelley Gang is written from the first-person perspective of the legendary Irish-Australian outlaw Ned Kelly:

“My 1st memory is of Mother breaking eggs into a bowl and crying that Jimmy Quinn my 15 yr. old uncle were arrested by the traps.”

The real-life Kelly left behind a fifty-six page letter about his life of crime. This primary source gave Carrey a precise model for how Kelly wrote. Once Carrey decided to us Kelly’s nonstandard language and sentence structure, he was committed to using it throughout the entire book.

Downside: You are limited to the vocabulary and diction of your historical character.

Third-Person Narrators

Third person narrators allow you to step back from the language of your characters. How far back you step depends on whether you choose a limited or omniscient third-person narrator.

Either way, this distance buys you some freedom from the obligation of writing in the voice of a historical character.

Denis Johnson’s novella Train Dreams tells the story of an early-20th century logger named Grainier. Johnson’s limited third-person narration keeps the narrative focused closely on Grainier’s personal life experiences:

“In his time he’d traveled west to within a few dozen miles of the Pacific, though he’d never seen the ocean itself, and as far east as the town of Libby, forty miles inside Montana. He’d had one lover—his wife Gladys—owned one acre of property, two horses, and a wagon. He’d never been drunk. He’d never purchased a firearm or spoken into a telephone.”

Because he is writing in the third person, Johnson is able to write about Grainier’s life more analytically than the Grainier’s first-person voice would have allowed.

Here are three important guidelines if you’re writing a third person narrator:

- Avoid modern slang or anachronistic references. Johnson lists things Grainer didn’t do, but he doesn’t mention anything Grainier wouldn’t have heard of.

- A third-person narrator looking backward from a later date may have more perspective. Too much overt anachronism, though, will undermine their credibility as a witness, and take the reader out of the story.

- The reader’s patience for researched information will be even lower with third-person narration. Too much third-person exposition can easily end up sounding like a textbook.

Outsider Narrators

Some authors use out-of-the-box strategies which allow them to tell a historical story from a more contemporary perspective:

- In her novel Kindred, Octavia E. Butler uses the sci-fi device of time travel to send her first-person narrator from 1970s California back to early-19th-century Maryland. This set-up allows Butler to write a novel about the experience of slavery without trying to recreate the 19th-century voice of an enslaved narrator.

- Jordy Rosenberg’s novel Confessions of the Fox is split between a slang-filled 18th-century British narrative and the accompanying notes of a 21st-century American scholar. Most pages include both third-person and first-person narration. This approach allows Rosenberg to portray the verisimilitude of a historical manuscript, while guiding the reader through it with a casual contemporary voice.

Contemporary narrators will have the same questions as the reader about a historical setting, so they can act as guides.

Downside: Adding a contemporary narrator requires you to juggle multiple time periods, rather than focusing on creating one historical period.

6. Writing Historical Dialogue

Dialogue is one of the trickiest parts of historical fiction.

If an author does not approach it strategically, their manuscript can easily become bogged down with overly-ornate and overly-involved dialogue.

These problems can also occur in first-person narration.

Keep Language Natural

Authors often make the mistake of trying too hard to make their language sound historical. This leads to stiff, awkward, and overly-formal dialogue.

Throughout history, people have spoken to each other in all the ways people speak to each other today:

- casually

- respectfully

- rudely

- sarcastically

- duplicitously

- flirtatiously

Focusing on period language more than on the motivations of the character speaking will undermine your scene.

At the same time, you don’t want your characters’ speech to sound inauthentic to their era.

There are some things you can do to avoid this:

Include Just a Dash of Period Language

It does not take very much period-specific language to flavor your speaker’s language.

Hilary Mantel, the author of the Wolf Hall trilogy, uses a technique of adding just enough period touches to create the feeling of 16th century English:

“I use modern English but shift it sideways a little, so that there are some unusual words, some Tudor rhythms, a suggestion of otherness.”

Even one or two words can be enough to invoke another time and place.

The first words spoken out loud in Lonesome Dove are delivered from Augustus, an old cattleman, to those pigs we saw on the porch:

“You pigs git,” Augustus said, kicking the shoat. “Head on down to the creek if you want to eat that snake.”

The only non-standard word here is “git,” a regionally-specific pronunciation of the word “get.” This pronunciation is appropriate for the character’s time and place. It also calls to mind the classic cowboy song, “Git Along, Little Dogies.”

The one word “git” does a lot of work. The rest of the line does not need any more non-standard language to make the reader hear it spoken in a “cowboy” voice.

Find the Right Words

When you are relying on one word or phrase to carry a lot of weight, it had better be the right one.

The only way to make sure that you are using authentic phrases is to draw them directly from your primary source research. Phrases that catch your attention will have the same effect on your reader.

Mantel noticed the repeated phrase “a little and a little” in the letters of Thomas Cromwell and borrowed it for her novels about him.

Keep a running list of interesting, noteworthy, or period-specific phrases as you conduct your research. If a term was used frequently in newspaper articles one year, it was probably used frequently in conversation at the time as well.

Refer back to your list when you are looking for language to flavor your dialogue.

Edit out Glaringly Contemporary References

Avoiding conspicuously anachronistic language is as important as including historical language.

Once a reader is caught up in your story, they won’t notice if your dialogue lacks any phrases indicating time period. They have accepted the reality of your historical setting.

Review your dialogue for idiomatic phrases which reference sports, technology, or culture. Edit out any phrases or words which would not be in circulation at the time your work is set.

- “It’s time to earn some moola.”

- “It felt like making a three-pointer.”

- “What’s up?”

- “That party was lit.”

- “His mind works like a machine.”

Ultimately, cut any modern language which will bump your reader out of the historical setting.

Limit the Amount of Direct Dialogue

A little bit of dialogue goes a long way.

Select spoken interactions can certainly do a lot to bring a reader into a scene, and to help them understand your characters and their relationships.

Pages and pages of back-and-forth, however, will tax a reader’s attention, bringing them right back out of the scene. Gratuitous dialogue can slow a story down as much as gratuitous description.

Strategies to avoid direct dialogue:

- Use indirect dialogue. Often, conversations between characters can be delivered as indirectly reported dialogue. This allows you to relay the content of the conversations succinctly, without needing to write out every word in a character’s voice. Indirect dialogue directly tells the reader about the topic of conversation. Example: “She listed all of the wagon’s contents, until I got tired of listening.”

- Use summarized dialogue. Summarized dialogue is even less specific than indirect dialogue. You can summarize an entire night’s conversation in a single sentence. Example: They talked deep into the night about the dangers of living on the frontier.

Readers will assume that the reported conversations are spoken in period-appropriate language. You maximize the milage of your previous dashes of historical language.

E.L. Doctorow’s historical novel Ragtime contains no direct dialogue at all. Ragtime covers a decade of early-20th century American history, and juggles the stories of dozens of characters, both real and invented. In order to pull this off in a quick-moving novel, Doctorow relies on indirect and summarized dialogue.

Pro tip: Save in-depth dialogue for the key interactions that you want to emphasize the most.

7. How to Publish Historical Fiction

Writing historical fiction is inevitably a time-intensive process. It takes as much research time as nonfiction, in addition to taking as much as drafting and revision time as any other type of fiction.

Once you have put in all this work into your manuscript, you will want to everything you can to maximize your chances of publication.

There are some steps you can take to help your manuscript get the attention it deserves:

Don’t Make this Query Mistake

Far too many historical novels are frontloaded with setting, character backstory, and other information, so the reader will have context for everything that happens. This approach risks losing a reader’s interest before you even get your plot started.

Editors and agents are busy people. If you don’t grab their attention on the first page, they might stop reading.

Here are three examples of the first lines of a historical fiction query letter:

- “It’s 1906 and Askuwheteu, an Ojibwe Indian, stands trial for the murder of a white man.” (Amanda Skenandore, “Aspen’s Way”)

- “It’s the story of the Japanese internment in Seattle, seen through the eyes of a 12-year-old Chinese boy, who is sent to an all-white private school, where he falls in love with a 12-year-old Japanese girl.” (Jamie Ford, “Hotel on the Corner of Bitter and Sweet.”)

- “Letters from Home is a 90,000-word WWII love story with a twist, aptly summarized as The Notebook meets Saving Private Ryan.” (Kristina McMorris, “Letters from Home”).

Do you see how each one of these combines historical place (time, location) with the story itself (trial for murder, boy in love with girl, love/rescue).

Just as you start your book with an exciting lead, you want to start your query letter that way. If you start your query letter with an engaging hook, the agent or publisher will be intrigued enough to learn about the historical context as they keep reading.

Fact Check Your Historical Details

All novels require editing and proofreading. But for historical fiction, you also need to fact check.

The last thing you want is for a reader to question your understanding of your historical period because you made a careless factual error. The reader needs to believe you have the authority to tell a story about this historical moment.

There are many type of facts you’ll want to check:

- Any time you reference specific historical events, re-check that the dates and chronology are right.

- When your characters use a specific piece of technology, re-check that it has been invented (and widely circulated) by the time your story takes place.

- The same goes for any references to books, songs, or trends: re-check your dates.

- If you are unsure if a word in dialogue is period-appropriate, look up the word’s earliest usage in a dictionary

When you reach the fact-checking stage, you will be glad you saved all your research notes.

Pitch Your Story, Not Your Setting

A lot of historical writers end up talking more about their setting and time period rather than their story. But what’s the difference?

Vivian Gornick makes a helpful distinction between “situation” and “story”:

“the situation is the context or circumstance, sometimes the plot; the story is the emotional experience that preoccupies the writer”

With historical fiction, we can make a similar distinction between the the historical setting of your work and your actual story.

Too often, when aspiring historical fiction writers are asked what their book is about, they make the mistake of going on about the culture, politics, and events of their historical period.

You need to be able to quickly tell a potential reader precisely what your story is about. Yes, you will mention the historical period when your story takes place. More importantly, though, you need to be able to say who your specific characters are, and what specific challenges they face.

When you can do this, you are ready to send your manuscript out into the world.

Ben Nadler is the author of the novel The Sea Beach Line. He is currently a Ph.D. candidate in English at SUNY Albany.