The keys to a story are the characters, and the key to characters is knowing the difference between round and flat characters.

The keys to a story are the characters, and the key to characters is knowing the difference between round and flat characters.

This way, you can be intentional about writing characters who make connections with your audience and also writing characters who support that connection.

When building a cast, it’s important to think about the function each character will have in the story. Their relationships to the other characters, especially the protagonist, will be the main factor that determines what type of character they should be.

Are there certain types of characters that are better than others? It depends. A better question might be, what is the best type of character for each role in a story?

We’ll get to know round and flat types, so that you as a writer are able to build the best possible version of the cast of characters for your next story.

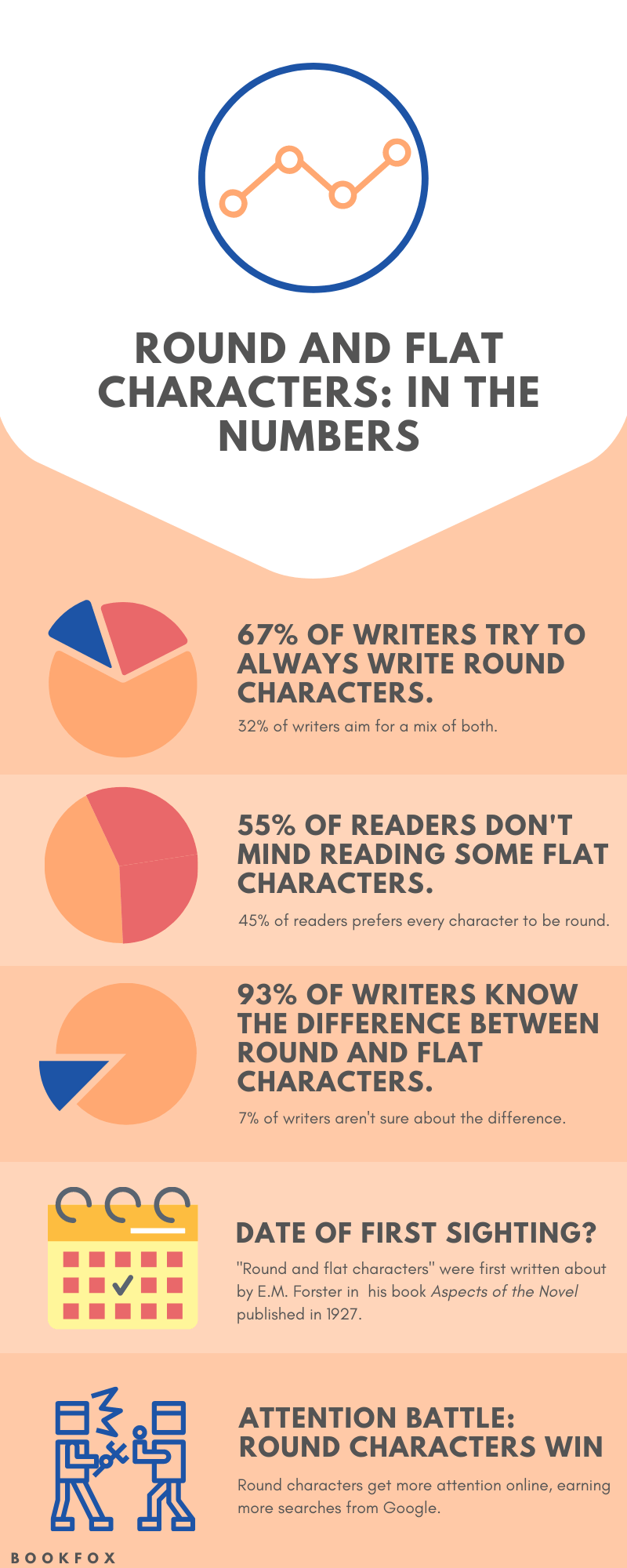

Round & Flat Statistics

How do writers think about round and flat characters?

Honestly, it’s surprising that so many writers always try to write round characters. I think this is a mistake, which I’ll talk about in the next section.

It’s also surprising that readers have such high expectations when they read a book, expecting that every character should be so wonderfully drawn — is there any room for minor characters?

In a recent Bookfox poll, we learned:

- 67% of writers always try to write round characters. 32% try for a mix of round and flat.

- 55% of folks said they didn’t mind reading some flat characters, while 45% said they preferred every character to be round.

- 7% of writers reported that they didn’t know what round and flat characters were, but 93% said that they did know the difference between the two.

The Round/Flat Character Myth

It’s a myth that round characters are better and flat characters should be avoided. There’s room in your story for flat friends.

E.M. Forester, author of A Room With a View and Howards End, came up with the term in his book Aspects of the Novel in 1927 and recognized that both types of characters are necessary. He wrote, “A novel that is at all complex often requires flat people as well as round.”

Round and flat characters work well in tandem. Together, they create the full cast of a story.

What is a Round Character?

Think of one of your favorite characters. What did you love about them?

Did you love that they struggled, that they grew, or that they surprised you?

Did you:

- Admire that Frodo, in Lord of the Rings, persisted in his journey even when it felt impossible and relied on his friendships to make it through?

- Relate to Mary from The Secret Garden, who explored in a time when she felt trapped and learned to love and heal because of her connection to nature?

- Connect to the inner turmoil Holden Caulfield went through in The Catcher in the Rye as a young person trying to find meaning in the world and in himself?

Well, they were probably round.

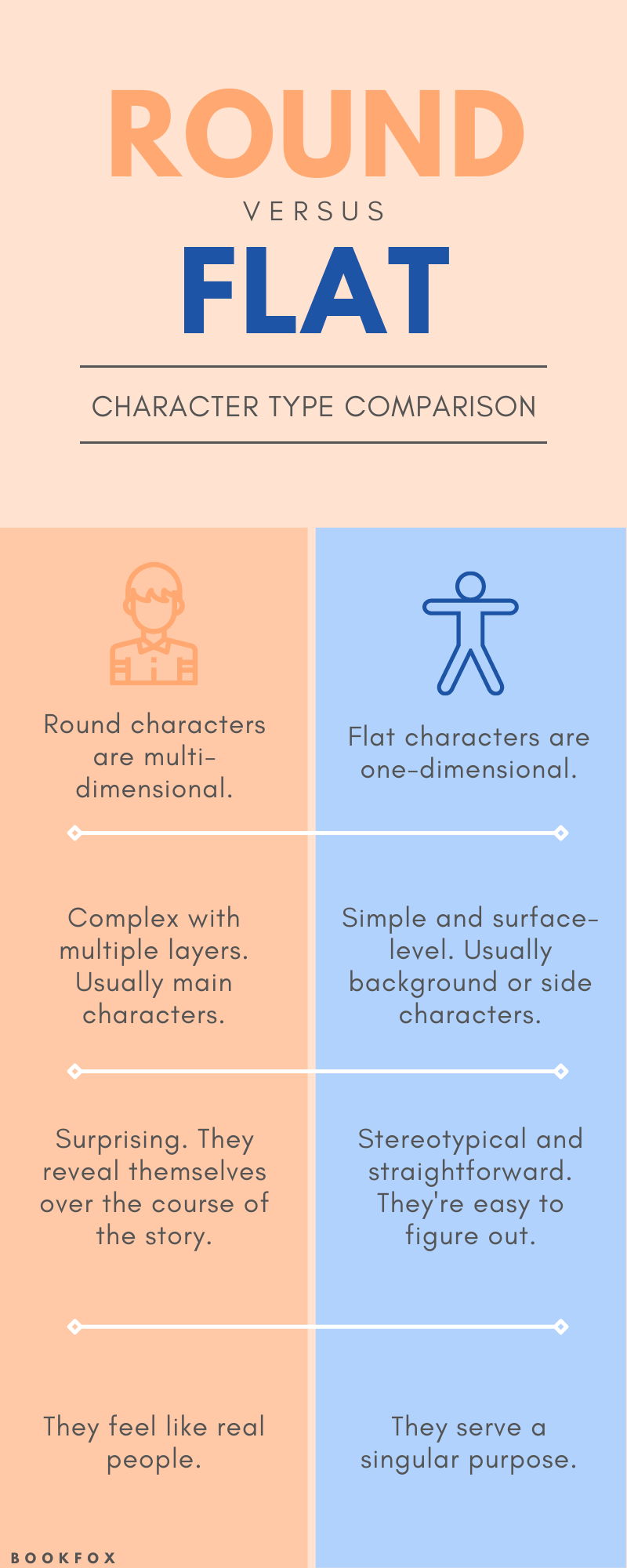

Round characters have layers. They’re multidimensional. They have depth, and they’re complex figures that the reader can get to know them over the course of a story. This is why they’re often the most memorable characters and why they might stick in a reader’s mind as their favorite.

7 Tips for Writing Round Characters

1. Round characters can only be built over time.

E.M. Forster, when he invented the terms “round character” and “flat character,” said that round characters “are fit to perform tragically for any length of time.”

Why did he say, “length of time”?

With round characters, we need the chance to get to know them.

That means it’s impossible to create a round character if they only get a few pages here and there in your book. It’s only through spending time with a character that the reader will feel like they are a real human being.

2. Round characters have to be surprising.

Forster argued that round characters need to be “capable of surprising in a convincing way.” Because they are not predictable, the reader feels curious and gets to learn more about them.

They’re more than a face we pass on the street, we spend time with them, they take up enough of the story to give the reader the chance to get a sense of who they are… and then feel surprised by them.

For instance, when Superman flies around the world to turn back time, that’s surprising:

- We knew he was powerful, but not that powerful (in a temporal sense).

- We knew he was good, but not that he would become so angry at death he would reverse the course of human history.

- We knew he was in love with Lois, but not that he prioritized her above all other humans.

A flat character can’t be surprising, because we assume that whatever they do is natural for them (we don’t know them yet). Only round characters can surprise, because they do something that’s beyond their surface-level personality and actions.

3. Round characters need to change in the eyes of the reader.

The reader needs to learn something new about the character over the course of the story—even if it’s something the character knew about themselves all along and it’s dramatically revealed.

- In “The Wizard of Oz,” Dorothy learns that she had her connection to home within her all along.

- In “Bright Lights, Big City,” the narrator gets to the far side of drug addiction and promises to change.

- In “Fight Club” by Chuck Palahniuk, the narrator becomes more and more extreme, turning into a domestic terrorist.

These changes make them intriguing and make them memorable.

4. Round characters’ actions have explanations.

Round characters have more reasons for what they do than flat characters.

They take a certain action or have a certain trait because of some fundamental part of who they are, or some event in their past.

For example:

- A character is sulky and brooding… because they’ve been through some tough times and have difficulty trusting people.

- A character is exuberant and wildly outgoing… because they’re trying to forget their painful past.

- A character is shy… because they’re nervous about approaching someone they really like.

5. Round characters need robust backstories.

Backstory and motivation can be helpful to think about when building out a round character.

If we know how a character came to be, this gives us a sense of their layers and depth. Like real people, round characters are complicated, and elements of their past can help explain why they do what they do.

Things like:

- Where a character is from

- Social and economic status

- Education

- Family and friends

These bits of background can all contribute to what a character chooses to do and why. And when that reasoning–the why–seeps into the story, that makes a character rounder.

For example, knowing that Hermione Granger in the Harry Potter series is from a non-magical family gives her depth. It helps explain why she’s a teacher’s pet and tries so hard in school. It tells us a lot about her personality and life experience.

6. Round characters need internal conflict.

Flat characters can survive with just external conflict. But round characters need internal conflict as well. This conflict is often at the root of what makes a character complicated and interesting.

For example, Shakespeare’s Macbeth is power-hungry when he murders the king to steal his crown, but there’s more to it than that.

- He’s trying to live up to expectations—of his wife, his friends, the mysterious witches, and ultimately himself.

- He’s kind of a tortured soul, and these desperate feelings make him compelling to the audience.

- He does terrible things because he wants to prove himself. Even though he’s a tragic hero and he goes to some awful lengths to get what he wants, we’re invested in his story and we want to find out how it ends.

7. Round characters have contradictions.

Good round characters feel like the Walt Whitman quote, “I contain multitudes.”

What are multitudes? They’re contradictions.

Take a look at Macbeth.

- He’s wealthy, powerful, and accomplished

- But we discover that he also has a huge capacity for weakness and fear.

These opposing forces feel real and relatable—perhaps especially for those of us who have experienced imposter syndrome—and they draw us in. It’s what makes Macbeth feel true to life.

If we remember that our readers are complicated beings themselves, putting complexity in our characters reflects that part of real life and lives up to what Forster knows round characters are capable of.

The “Life” of Round Characters

“[A round character] has “life within the pages of a book.” – E.M. Forster

“Life within the pages of a book” is pretty much the highest compliment any writer could get on their work. That feeling is what readers love most about reading. And round characters are the way to get there.

All this combined is what is at the core of a good round character—they feel authentic. They feel like a real human person, in all their contradictory, complicated, messy, and beautiful imperfection.

What is a flat character?

Flat characters are surface-level and one-dimensional. But this isn’t a bad thing—2D animation can be just as good as 3D animation.

Forster said that flat characters ought to be “constructed round a single idea or quality.” So we’re working with one high-quality single layer as opposed to the many layers of round characters.

If round characters are meant to be surprising, then flat characters should be predictable.

Predictability has its place in every story. If a hero is on a chaotic quest, that chaos will be emphasized if we catch glimpses of the normal everyday world and the people who live in it, the ones who are the opposites of our complicated round characters.

When should you write flat characters?

1. To fill out the world of the main characters.

Sometimes, flat characters are the ones we meet only for a moment, like extras in a film.

They make the main (round) characters feel more real just by being there and filling the world with extra life.

- Rex in Toy Story adds to Woody’s world because he’s a part of Woody’s group of toys. He adds humor, but he doesn’t drive the plot.

- Prim in The Hunger Games is a catalyst for the plot, but she’s very predictable and innocent every time we meet her, so we know she doesn’t have many layers.

- Zazu in The Lion King is a supportive force and helps the main characters, but we don’t learn a lot about him.

2. To write a certain genre.

Flat characters can be main players in a story, too, if you’re writing a certain type of book. Some great examples of active flat characters are all throughout these genres:

- Fairy Tales. Little Red Riding Hood is only pure and good, and the wolf is only evil and hungry. These characters are very straightforward, and the reader understands what they’re all about right away. The surprise in this story of the wolf in the grandmother’s house comes from the plot, not the characters themselves.

- Kafka books. Franz Kafka is the main example of this, of course, but in a Kafka book, important characters don’t have a name but only a title, like “The Chief Clerk” or “The Hunger Artist.” Often his main character has only an initial: “K.” That’s because his characters are the definition of flat characters — they’re not meant to be real, they’re meant to be an “everyman.”

- Parables. Think of all the Aesop’s fables. These are almost one-dimensional characters — 2 dimensional at their best. But they fulfill the purposes of the story.

Flat characters like this often fit a “type” or trope and don’t stray from that stereotype.

This doesn’t mean that they’re bad characters—we love Little Red Riding Hood and the wolf, and it’s a story we tell over and over again. It just so happens that the type of story—a fairy tale—calls for the simplicity of a surface-level character to convey a direct and uncomplicated idea.

How to write flat characters well

Flat means a character is just “action/trait” without much justification behind it.

For example:

- The next-door neighbor in a story is nosy.

- She spends all day peeking through the curtains with binoculars.

- …but we don’t know why.

- She appears in just a couple scenes.

- She’s predictable, and that’s okay.

Flat characters should be easy for an audience to understand quickly. We know that character is nosy as soon as our main character spots them peeking through their curtains with their binoculars. Immediately, we know their type, we know their whole deal.

In the same way, with a fairytale character, we know that the wolf is bad as soon as he appears. It doesn’t take the reader long to catch on, and because the wolf is flat, we know he won’t surprise us at any point. The wolf isn’t a tragic anti-hero with a complicated past—he’s just a hungry, conniving villain.

Be intentional about flat characters

When they’re used consciously and effectively, flat characters really make a story shine.

Have an idea of what function your flat character will serve in the story, and stick to that goal as you’re writing them. Functions for flat characters include expanding the world, advancing the plot, and serving as a foil for the main character.

Think of Romeo and Juliet.

Lady Capulet and Lord Montague are flat characters.

- They’re foils to Romeo and Juliet.

- These two characters hold a grudge against one another and their families.

- We don’t know the backstory of their motivation.

Romeo and Juliet are round characters.

- Surprise: they break out of what their families expect of them.

- They are complex—they oppose the simplistic war between their families.

- They have strong internal conflict in the form of star-crossed love.

Because Lady Capulet and Lord Montague are foils, or opposites, to Romeo and Juliet, their function is to highlight the stakes of Romeo and Juliet’s secret love.

Flat characters usually work best in supporting roles or as background characters in a story about a round character.

They also work very well in a very simple story like a fairy tale or myth. As long as they’re well placed in a narrative and/or genre, they’re excellent tools.

Main Problem with Flat Characters

E.M. Forster said that the main problem with flat characters is not that they are flat, but that they “pretend to be round.”

If a writer creates a character thinking that they’re round, but the reader perceives them as flat, that’s the fatal error.

Flat characters only weaken your writing and make it seem simplistic and boring if flat characters end up in the wrong part of your story.

It probably isn’t a good idea to have the main character of your family drama be a flat character. But if the main character’s selfish uncle is a flat character, that could be a fun way to advance the plot and flesh out the setting.

Are dynamic/static characters different?

Yes, those are different than flat/round. The terms dynamic and static are often brought up when talking about round and flat characters, but they aren’t synonyms.

A dynamic character is a character that evolves over the course of the story.

- Their plot arc makes them grow as a character.

- They change by the end of the story.

A static character, as you might be able to guess, is the opposite.

- They don’t have a developing arc.

- They remain consistent throughout the story.

Dynamic and static are subsets of round/flat. In other words, one of the things that make a round/flat character include such characteristics as dynamic/static.

Dynamic/Round and Static/Flat

- If your hero journeys into a dragon’s lair, makes it out with some gold, but learns that the real treasure was the friends they made along the way, your hero is probably a dynamic and round character.

- If your character runs a shop in the village and sells a shield to that hero before going back to their everyday business, they’re probably static and flat.

- But maybe a character in your story is an old wizard, and they serve as the role of mentor for another character. Your wizard is set in their ways, and they don’t change over the course of the story, so they’re static. But they can still be interesting and realistic, with lots of layers of their life experience to make them feel like a real, fascinating person, and that could make them round.

So, mixing and matching is possible. Round characters might grow over the course of their story, but they don’t have to. And flat characters might remain the same throughout the plot, but not necessarily.

Again, it depends on what the character’s role in the story is as to whether they will be flat or round, dynamic or static.

When to choose round or flat characters

So, most folks agree on the basic concept of round and flat characters, but it’s tricky to tell when a character needs to be round versus when they need to be flat.

Round characters are are complex, surprising, and feel like real people.

Flat characters are simple, stereotypical, and serve a singular purpose.

The protagonist and leading cast of characters will usually be round. If a character is a main part of the story, we want them to be interesting. We want them to feel alive, as Forster would say, so that the reader can feel interested in them and engage with the story through them. This happens best when a character is complex and layered, surprising and interesting.

Flat characters are usually in the background. They work well as supporting characters, or main characters if you’re telling a very simple story like a myth or parable. They’re simplistic and unsurprising, but this reliability can help to build the foundation of a story. While round characters might be more unpredictable, the flat ones are there to offer some stability.

Questionnaire to Help You Decide on Round versus Flat

If you’re struggling to figure out whether a certain character should be round or flat, answer these questions:

- Does this character appear in a significant portion of the book?

- How long should it take for the reader to understand this character?

- Does the character exist simply to fulfill some section of the plot?

- Does the character need a backstory?

- How often does this character interact with your protagonist?

- Do you want this character to be especially memorable?

- How realistic is this character?

- Does the character have any internal conflict?

- Will this character change at all over the course of the story?

- Will this character surprise the reader?

Balance Your Round/Flat Characters

Don’t attempt to write all round characters.

Not only will it take up way too much time and effort, in the end your book will be weaker because of it — because the reader will be confused about what character they need to care about.

The trick is getting the right mix between round and flat characters, and striking that balancing act is one of the toughest jobs of the writer.

Different shapes, like round and flat, will fit together differently depending on the story you’re trying to create. Never be afraid to experiment with the tools you have—like playing colored wooden blocks when you’re small, writing is often at its best when it’s playful.

With any luck and with some strong character choices, your readers will come away feeling as though they’ve experienced something real and true to life within the pages of your book.

One thought on “Round and Flat Characters: A Guide to Writing Characters”

Great advice! This has been very helpful in my character development.