Steve Erickson’s books are not, usually, an easy read. Or the reading itself isn’t difficult, it’s just the understanding part. He’ll employ unorthodox typography with the frequency of Mark Danielewski and use a Haruki Murakami-esque technique of channeling the narrative into the hyper-personal psychic journey of the hero.

Steve Erickson’s books are not, usually, an easy read. Or the reading itself isn’t difficult, it’s just the understanding part. He’ll employ unorthodox typography with the frequency of Mark Danielewski and use a Haruki Murakami-esque technique of channeling the narrative into the hyper-personal psychic journey of the hero.

The result is always intellectually delightful to read, if not the type of novel you’d want to have to dissect, part-by-part, explaining the pieces and their contribution to the whole.

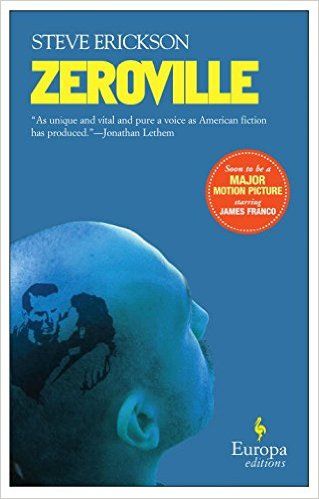

In Zeroville, an ex-seminarian student named Vikar, identified as a cineautistic, has a shaved head with a tattoo of Montgomery Clift and Elizabeth Taylor (and assaults anyone who misidentifies them).

He is anti-drug, doesn’t understand comedies, has a penchant for violence, and falls in love with a woman named Soledad Paladin. Above all, he’s a genius at editing and understanding film sequence – or rather, that film has no sequence, no proper time — and that genius leads him to start tracking down the single frames from a reoccurring dream he’s had since childhood.

The book’s structure consists of a series of numbered sections – a reference to movie frames, or scenes – which climb to 227 before falling down the back side of the book down to zero. It’s not unusual for Erickson to play with structure in his books — in Our Ecstatic Days he had a separate narrative running through a single line two-thirds of the way down the page, and in Tours of the Black Clock he has 164 short chapters. Contrary to expectation, the brief sections (some even don’t reach sentence length) don’t create discontinuity in the narrative, rather, they offer a steadily escalating structure to the book that makes the story feel more unified.

Zeroville is more accessible than his last book, Our Ecstatic Days, but shares the same emotional heart, as both are about the death of a child.

Except in Zeroville, it’s a variation on a theme, with the narrator waxing Kierkegaardian about the necessity of fathers (Abraham, God the father, Vikar’s father) to kill their children. Along other religious lines, Vikar has replaced the authority of religion with the authority of cinema. In a model of a church he created, Vikar has replaced the altar with a cinema screen. Even to pay his respects to the dead, he goes not to the graveyard but to the movie theater. All these replacements of religion with cinema serve as a rather damning portrait of the deification of film, certainly an apt representation of contemporary culture.

Appropriately enough, the rifts on cinematic knowledge are Midrash-like in their detail and complexity of interpretation – and there are quite a few. Long-winded diatribes debating over the finer meanings of the song about the dog in Now, Voyager, homage to Mogambo, The Long Goodbye, and Heiress; summaries of half a dozen films from around the world — The Lady Eve, a few unnamed Japanese films. Zeroville is, on a fundamental level, a love song to film, to the history of film in all its artful incarnations. The reader who catches the many allusions and references will be reading a much richer, funnier novel, but it doesn’t take an encyclopedic knowledge of film to enjoy the story.

As is common for Erickson, the novel traffics across the geography of Los Angeles – PCH to Zuma, Sunset, Laurel Canyon – and even imagines disasters such as an earthquake triggering a tidal wave down a Santa Clarita valley. The geography is recognizable and yet not – all the places are seen through a nightmarish, dreamy filter. In addition, there are interludes in Spain and France – other command centers for cinema – which contain stories that are no less entertaining for being narrative sidebars.

Zeroville is one of Erickson’s most accomplished works to date, a dangerous, sexy romp through the history of film and one man’s savant-like obsession with the meaning of film. There’s not any novel like it, because no one writes like he does.

In fact, the highest praise I can offer to Erickson is that in every book it seems like he’s broken the emergency-stop of his imagination and let a meltdown occur, and we all get to the watch the highly dangerous but highly fascinating fallout.

2 comments

Zeroville is fantastic. One of Erickson’s best.

I recently conducted an in depth interview with Erickson for ChuckPalahniuk.net. Check it out.

https://www.chuckpalahniuk.net/features/interviews/steveerickson/

-thejamminjabber

https://thejamminjabber.wordpress.com/

I stayed up until 1 a.m. last night finishing “Zeroville.” Two concepts which struck me the most were, one, that God hates children, and two, that the doorless church is to keep you in, not out.

Having grown up in a staunchly Mormon family, even serving a two year mission for my church – at my expense – I especially resonate with these concepts. In all of the religious studying I have done, it has never occurred me that it is always the children that suffer. Isaac at the hand of Abraham, Pharaoh in Egypt’s own son and the sons he sent his soldiers to murder, God sending his own son to suffer, and so on. In word, who can possibly believe in a god who demands a father murder his own child.

When someone is raised in a particular religion, told repeatedly that it is the only true church (as was my case in Mormonism) , it is almost impossible to get out. Not the organization per se, although that is challenging because they just don’t want to let you go, but the idea of God, Heaven and Hell, the years and years of brainwashing that has been drilled into your head since childhood. It takes a long time for the guilt to go away. Not the guilt that now you are doing things that we strictly forbidden by the organization, but the guilt of wondering if you were wrong to leave that organization, if it were right after all. If you have turned your back on god. It’s the notion and existence of god that is hard to get out of.