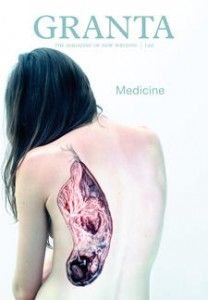

Granta’s latest theme is “Medicine.” Who better to write about medicine than a practicing pediatrician and a man named to the New Yorker “20 under 40” list?

Granta’s latest theme is “Medicine.” Who better to write about medicine than a practicing pediatrician and a man named to the New Yorker “20 under 40” list?

Chris Adrian kicks off the latest issue with “Grand Rounds,” a story unlike his other fiction. It’s a transcript of a speech given to other doctors, so it’s all dialogue. The speaker, who as a gay pediatrician storyteller seems to resemble Adrian himself, wanders through a host of topics: the intersection of narrative and medicine, the death of his mother, and a discarded story about teddy bears.

Let’s start with teddy bears. The teddy bears are very meta. Apparently, the teddy bear story is an earlier draft of this particular story:

“So I’ll just tell you about the teddy bear story. I’ll sum it up. It’s not that great, anyway. There are these bears and a little girl and some aliens and a shrink ray. And her doctors get shrunk and have an adventure inside her body and there are some magic ponies who are ultimately responsible for all the sickness and confusion and unhappiness in the girl and the hospital and in this country.”

This sounds like a Chris Adrian story, or at least a hyperbolic description of one. Remember, the original version of “The Children’s Hospital,” before McSweeney’s edited it, had aliens at the end. And substitute avenging angels for magic ponies. And he writes about fairies in “The Great Night.”

But then he gets advice to change the Teddy Bear story into a different type of story, the type of story that ends up being “Grand Rounds”:

“So you can see that Dr. DasGupta has them try different things with the story. She sets up some hoops and asks them to jump through, as it were. Try writing from the point of view of the patient’s body or even a body part. Try switching up the genre — write the story as a poem or a regular essay or a TV show or a commercial or a play. We had an interesting discussion about how her students sometimes only discover what they want to tell, how they discover what part of the story really matters, as they switch it or carry it from form to form and find which part stays the same amid all the changes. I told her I was working on something that started as a story and became a novel and then an essay before it was finally a graphic novel about the demon that possesses Linda Blair in The Exorcist, but that it was really about my mother.”

And so “Grand Rounds” is the story about his mother. Which is where, despite the absence of teddy bears, aliens and shrink rays, the story gets weird. The protagonist says that when he was a child he wanted to be sick, because when he was sick his mother was nice to him. What follows is an economy of sadism, a trading back and forth of meanness where son poisons mother and mother hammers son, and yet you get the sense that both crave these violent exchanges and somehow need them.

Why is the story about his mother better than the teddy bear story? In other words, as he frames it within the story, why is the straightforward truth more powerful than all the inventive flights of fancy he usually uses in his fiction?

“So [the mother story] is a better story. That’s better than magic ponies and teddy bear picnics and whatever else that other one was about — I can’t even remember any more because this one is better. This one is perfect. Do you understand why it’s perfect? Not because it’s true. You can never know if it’s true or not. It’s because the story and the life that it’s based upon are the same thing. Because the story and the troubling thing that gave birth to it are the same thing. Because the story and the trouble are the same thing.”

So within this story you have an evaluation of what is a worthwhile narrative and how some fictional attempts can impede the stories we need to tell. It’s wise and good and raw and Adrian at his best. Although this story is in line thematically with all his other work, it’s also stepping beyond it.