Every writer has to know how to create suspense.

If you can’t create suspense in your book, readers will always feel shortchanged and indifferent to your story. Suspense is THE crucial technique to creating a riveting plot.

Creating suspense is really about evoking an emotion in the reader, an emotion akin to happiness, sorrow, or anger.

Specifically, suspense is the feeling of anxiety. But good anxiety! Stories help us to stop feeling anxiety personally by creating anxiety and then flushing it out (if you care about Greek storytelling technique, this is Aristotle’s notion of “catharsis.”)

Key Steps to Creating Suspense

There is a simple, two-step process to creating suspense.

- Trigger a Story

- Delay

It seems like it should be more complex than this, doesn’t it? But every single method of creating suspense (check them out below) uses this technique.

What exactly do I mean by triggering a story?

- A glance across a room (is it love?)

- A gun tucked under a shirt (how will it be used?)

- Two criminals meet for coffee (what will they plan?)

That’s the initial suspense of your story. This suspense will run throughout your entire book. Sometimes it’s called the “plot engine,” because it’s what keeps the reader reading. Without it, no one will finish reading your book.

There’s a second kind of suspense, and this is called “scene suspense.” It’s suspense that is created and resolved within a single scene of your book.

- Two characters in love are very close to each other, and by the end of the scene, they kiss.

- Two people are fighting over a gun, and in the end, someone is shot.

How to Delay

You would think that readers would hate an author who delayed giving them what they want. In our culture of instant gratification, how can an author get away with constantly delaying the resolution of a plot?

But as it turns out, all readers want is that feeling of not knowing. Of anticipation. And the longer you make them wait for it, the more powerful the story will be when it finally resolves.

- Keep the story balls aloft. You have to keep reminding the reader of what is at stake. Remind them of the answer they want.

- Tease the reader. Yo-yo between almost resolving and then pulling back. If you keep a steady delay, it’s not nearly as powerful as swinging wildly between almost resolution and holding back.

So let’s get into specifics about how to create delay.

All the 25 methods below give strategies for how to delay your story so that the suspense is gripping.

1. Use a Suspense Object

In the movie “Tenet,” directed by Christopher Nolan, there’s a fight between John David Washington and a man in a black suit, and they wrestle over a gun. The gun is the suspense object.

- The gun is fired multiple times, but never hits a character.

- Both characters end up grabbing the gun, but it’s always dislodged by the other character.

- More than three times, the gun skitters down the hallway, out of reach.

The presence of the gun ignites and invigorates that entire scene. The battle is structured around the object of the gun, and as readers, we feel like the stakes are high because at any moment a person might die.

Without a gun in that scene, there would be very little tension. We might worry that a character would get beaten up, but not die. And this technique is fairly mythological, where characters fought over weapons like King Arthur’s Excalibur.

The object doesn’t have to be dangerous, like a gun. Think of another Christopher Nolan film, “Inception.” In that movie, the spinning top is the suspense object.

2. Look to Mother Nature

The weather is the arch-villain and antagonist in many books, and provides all the suspense necessary for a good story.

- In “Salvage the Bones” by Jesmyn Ward, Hurricane Katrina is bearing down on Mississippi, and the story follows a family as they try to prepare for it.

- Jack London uses this technique repeatedly through his entire corpus. Think of “To Build a Fire,” where a man attempts to avoid freezing to death. Or in “Call of the Wild,” how Buck struggles in the harsh weather of Alaska.

- The book “Endurance” takes a similar tact, as their boat gets stuck in ice and they have to struggle for months to escape Antartica.

Mother Nature can create ongoing suspense (like “Endurance”) or can work on the basis of anticipation (like “Salvage the Bones”).

3. Create Hair-Trigger Danger

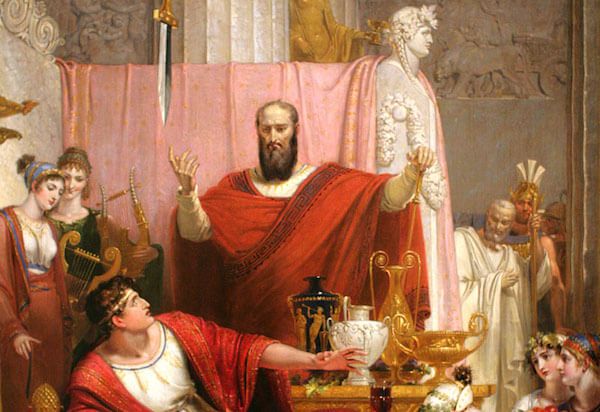

Once, a man on a throne had a sword suspended over his head by a horse’s hair. At any moment the sword might drop and cleave him in two. This was called “Damocles Sword,” and it became a metaphor for living in constant danger.

We see this technique in movies like “Speed,” with Keanu Reeves and Sandra Bullock, where at any moment, if they stop driving the bus, the bomb will explode.

To use this technique, simply devise a way to have physical danger that could occur at any moment if:

- a finger is lifted off the trigger

- any sound occurs

- two characters stop holding hands

And then don’t have that event happen: Delay. Keep the reader in that awkward space for as long as possible.

4. Insert a Ticking Clock

In Edgar Allen Poe’s “The Pit and the Pendulum,” the narrator is strapped to a table while a pendulum with a scythe on the end of it swings over him, descending lower and lower. We know the narrator has only a limited time before the blade on the pendulum starts slicing his body.

We see a similar technique in Star Wars IV, when the garbage compactor is closing in on Luke, Leia and Han Solo. As the walls close in, they realize they only have a minute to live unless R2D2 can stop the compactor.

Almost every popular story uses the ticking clock technique by imposing an artificial time limit.

- You only have 3 days to find the fissile material

- You have 48 hours to find the kidnapped girl

- You have 24 hours to make it through an entire season and torture 76 people along the way (Jack Bauer!)

Simply choose a built-in time limit for your story, after which the hero will fail.

5. Create an Ominous Person

In Joyce Carol Oates’ story, “Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been,” we see a threatening man in a gold convertible tell 15-year-old Connie:

“Gonna get you, baby.”

That man, Arnold Friend, comes to Connie’s house, threatens her family and neighbors, and rapes her before kidnapping her.

All the suspense comes from that initial meeting, though. When he’s just a man in a gold convertible and he catcalls her. We know from that instant that he’s going to show up again, and spend the rest of the story worrying about it.

6. Repetition as Suspense

In one of the best episodes in “Battlestar Galactica,” we see humans in a fleet of spaceships running away from Cylons, the robot enemies. Except every 33 minutes, the Cylon spaceships jumps through hyperspace after them, and the humans have to jump to escape them. If the humans don’t jump every 33 minutes, they will all die.

The suspense here accrues through steady intervals. Every single time the humans are forced to escape, we wonder:

- whether the missiles will hit them before they can jump

- how they will finally escape

- whether exhaustion and infighting will lower the human’s chances

After 130 hours, with about 250 jumps, the humans finally find a way to break the pattern. This cyclical way of creating suspense again and again uses repetition in an ingenious way to rivet the viewer.

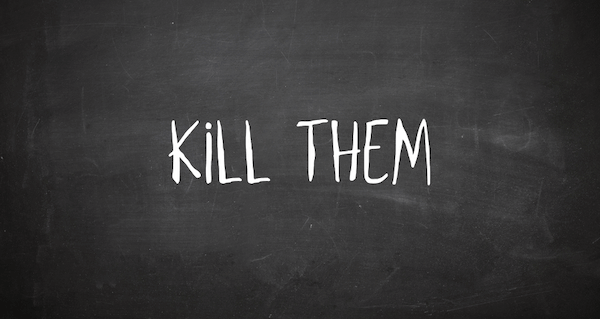

7. Creating Suspense through Hindsight

In David Foster Wallace’s “The Soul is Not A Smithy,” a teacher with a classroom of kids writes “KILL” on the chalkboard. He erases it, then writes KILL THEM.

After a few more minutes, he starts writing KILL, KILL, KILL THEM ALL KILL THEM DO IT NOW KILL THEM. He keeps on scrawling things like this while uttering a high pitched whine, and the children flee the classroom except for four children too afraid to move. In the end, the police shoot the teacher.

Now, the KILL THEM part doesn’t happen until halfway through the story. How does Wallace create suspense before that point?

Well, he creates suspense from the very first line, which mentions a newspaper headline: “Four Unwitting Hostages.” That’s because the narrator’s telling this story as an adult, thinking back to what happened. Hindsight creates all the suspense. He tells us the end of the story before the story even begins.

As the narrator remembers this story and offers commentary alongside the events of the story, we’re know something horrible will happen but keep reading to see how exactly it will unfold.

8. Employ Dialogue to Delay

If suspense is all about delay, then dialogue is one of the best ways to create that delay.

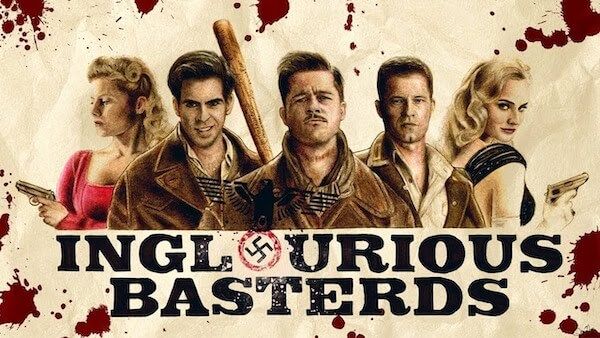

Quentin Tarantino is a master at this. Look at “Inglourious Basterds” at you’ll see two scenes that use dialogue to create suspense.

- The Jew Hunter, played by Christoph Waltz, walks around a house where Jews are hiding under the floorboards. He compliments the daughters, he talks about the farm. It’s a very long scene, with five minutes of innocuous dialogue, and the whole time we’re wondering when violence will explode. Finally, it does, as the Jew Hunter shoots the floorboards where the Jews are hiding.

- The bar scene, where American spies are posing as Germans officers. For almost 8 minutes, they are cordially questioned by another German officer, with dialogue that shows he’s doubting their identities. Finally, finally, they give themselves away with a gesture, and there’s a shootout where almost every dies.

If The Jew Hunter just walked into the house and started shooting, or the German officer figured out right away that the Americans were imposters, the scenes would be dull. It’s the anticipation of violence which creates all the suspense.

9. Chekhov’s Gun Suspense

There’s a rule called “Chekhov’s Gun” where if the reader sees a gun on the mantlepiece, that gun must be fired before the end of the story.

Obviously, this rule is much bigger than just guns. Any object gives the reader expectations.

When you show the reader a compass or watch or knife, you must fulfill your storytelling obligations by making that object significant for the story.

So you create suspense by showing characters objects — because the reader wants to keep reading to discover how that object affects the plot.

In Haruki Murakami’s “UFO in Kushiro,” a man is asked to deliver a mysterious box. He is not allowed to look at its contents.

So obviously, the reader is wildly curious about what’s inside this box, and keeps reading to discover the contents.

10. The “Jinx” Method of Suspense

If a character thinks or says something hopeful, the reader knows they’ve jinxed it, and something bad will soon happen. That expectation of the terrible thing creates suspense for the reader.

- “I’m so glad this is all over.” (disaster is coming quickly)

- “I was so lucky to finally find the love of my life” (she’s about to cheat on you)

Because the reader can sniff out these lines where characters jinx themselves, they start expecting a disaster — and that expectation is called suspense.

11. Setting as Suspense Device

In Pinocchio, when all the boys have found a paradise called “Pleasure Island,” where they can gorge themselves on cotton candy and enjoy carnival rides, the reader knows it can’t stay this way. And of course there is a dark underbelly, as the reader expected, as the boys are turned into donkeys and sold.

A happy place — because it’s too happy — creates suspense for the reader.

On the other side, a creepy setting also works as a suspense device, particularly creepy houses.

- Shirley Jackson’s “The Haunting of Hill House“

- “The Turn of the Screw” by Henry James, with a haunted house

- Stephen King’s “The Shining” is simply a haunted hotel

12. The “Splendid Day” Technique

When things are too good in a book, we know something bad is about to happen.

That’s because there isn’t any story if nothing goes wrong. Every story has something go wrong.

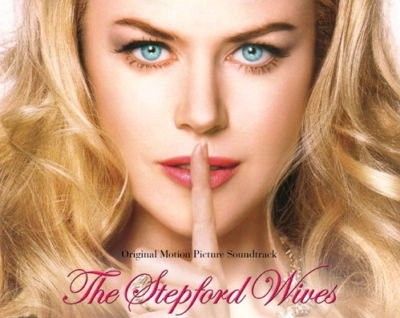

Think of the polished happiness of “The Stepford Wives,” where the wives are all ideal — too ideal.

- They fawn over their husbands

- Their houses and yards are always pristine and clean.

- They never lose their temper or feel any range of human emotion

The perfection is grating. So we learn that they are robots, or cyborgs, or hypnotized (depending on the version), and then the story really gets started.

When everything is “splendid,” the reader is anticipating the “turn,” where we learn the truth, and will keep reading to find that turn, always thinking it’s right on the next page.

13. Introduce “Red Shirts”

In Star Trek, the unnamed characters who accompany Spock and Kirk always get killed first.

For some reason they always wore red shirts. So “Red Shirts,” became a term for disposable characters. These are minor characters who can be killed easily, which heightens the tension for the main characters.

To create suspense, all you do is introduce unnamed or lightly developed characters in a tense or dangerous situation. Then the “Red Shirts” are killed, or mutated, or lose a limb, and suddenly the reader is truly worried about what will happen to the character they love.

*And no, they don’t have to wear red shirts for this to actually work.*

14. Unreliable Narrators

In Gone Girl, we have two narrators, husband and wife, who are notorious liars. What’s more, they’re not just lying to themselves, or to each other, but they’re also lying to us, the readers.

As the novel progresses, and we see that Nick was lying about his infidelity, and that Amy was lying about being dead in the first place, the reader starts questioning whether anything they’re reading is true.

The Unreliable Narrator technique not only creates suspense for the future, it also creates suspense in the past (it’s the only technique that works this way!).

It casts doubt on everything the reader has read so far.

15. Build Suspense with a List

This sounds like the worst idea on this whole post. Seriously, a list? What can a list do?

Well, look at Lee Child’s novel about Jack Reacher, “Gone Tomorrow.” Jack Reacher is riding the subway late at night with only a few other people when he notices a woman who’s acting strangely.

Reacher runs down a list of twelve points that identify a suicide bomber. And as he goes through each one, step-by-step, from inappropriate clothing to breathing patterns, the reader begins to get more and more worried that this random woman on the New York subway really is a suicide bomber.

By the time Reacher reaches the end of the list, which takes the first two and a half chapters, we’re sure that at any moment this woman will pull a switch and detonate the explosives hidden underneath her bulky coat — and Reacher’s worried about the same thing.

16. Make a Character Lose Control

When a character isn’t in control of themselves, there’s no accounting for what they might do, and that unfettered possibility terrifies the reader.

There’s a suspicion that the loss of control can lead to anything — suicide, mass murder, rape, or acts of unimaginable cruelty.

This loss of control creates suspense because we’re wondering what this unhinged character will do. And you can get to this loss of control by any number of ways:

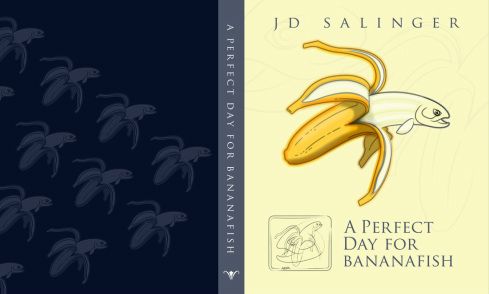

- PTSD. Look at J.D. Salinger’s story, “A Perfect Day for Bananafish,” where a man recently back from war commits suicide.

- Demonic Possession. In the HBO version of “The Outsider” by Stephen King, we see a police officer become possessed by the malevolent force “El Cuco,” and that creates one of the main sources of tension.

- Drugs/Alcohol. Denis Johnson’s protagonist in “Jesus’ Son” is constantly out of his mind on pills, and you can never predict what wild hallucination he’ll have next.

- Unexplained Medical Conditions. In Joshua Ferris’ “The Unnamed,” a man randomly feels a compulsion to start walking. And he’ll walk, without being able to control it, for 6 to 12 hours, until his feet turn bloody and he collapses.

From nervous breakdowns in “The Yellow Wallpaper,” to sociopaths in “The Red Dragon” by Thomas Harris …

from delusions in “Shutter Island” by Dennis Lehane, to rare disorders of the mind in “Atmospheric Disturbances” by Rivka Galchen …

poor mental states that don’t allow a character to be in control of their faculties always get a rise from the reader.

17. Home Away Home Technique

Some people say there are only a few stories in the world. Kurt Vonnegut mapped out the classic 8 forms in his speech on story shapes.

One of the classic forms is a person leaves town and tries to get home again.

- This is as classic as Odysseus in “The Odyssey,” fighting through sirens and monsters to get home to his throne and his wife.

- Or think of “Alice in Wonderland,” how her only goal through the whole book was to get back home.

- Or Dorothy in “The Wizard of Oz” is on a journey to try to get back home.

- The subtitle to J.R.R. Tolkien’s “The Hobbit,” was “There and Back Again.” Classic story structure, right in the title.

So when you make a hero or heroine leave her home, the reader is in suspense until you return them back home again. That’s the thing the reader really keeps reading for.

The structure of Home-Away-Home works a little like an unresolved chord in music. Try singing “Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star,” and not saying the very last word, “are.” Frustrating isn’t it?

In a similar way, the reader wants the story resolved back to home, and will keep reading until that resolution is reached — not because they want to see whether it will happen, but because they want to see how it will happen.

18. Start at the End

In Chuck Palahniuk’s novel, “Fight Club,” the novel opens at the end of the story, with Tyler Durden pushing a gun into the mouth of the narrator. Surrounding them are buildings with explosives packed around the foundational pillars.

So we have two ticking clocks:

- How long before Tyler Durden kills the narrator?

- Nine minutes until the bombs go off

And then we swing back to the beginning, to learn how the narrator first met Tyler Durden, and how they developed an underground fight club.

All the suspense of the entire book comes from starting at the end, since the reader wants to know how the story will end up at that crazy and violent conclusion.

19. Use Mystery

Of all the advice given here, mystery is probably the most obvious technique of all. It’s probably the first thing you thought of.

After all, any mystery has suspense embedded in it — the reader is suspended until they reach the solution to the mystery.

Think of two types of mystery:

- Macro Mystery. This is a mystery that extends across the entirety of a book.

- Think of Steig Larson’s “The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo,” where disgraced journalist Mikael Blomkvist takes on the mission of finding the murderer from a 36-year-old case.

- Micro Mystery. This is a small mystery that lasts only for a scene.

- At the end of the movie “Seven,” a delivery vehicle delivers a box to two detectives in the desert. The first mystery is: why did a delivery vehicle come out to the middle of the desert? The second mystery is: what’s in the box? No one could have guessed that it’s the head of the pregnant wife of one of the detectives.

20. Develop Codes

When you mention code-breaking in novels, most readers instinctively think of “The Da Vinci Code.” But if you’re looking for a more sophisticated take, I would recommend Umberto Eco’s “Foucault’s Pendulum.”

It’s got math, medieval mystery, and a heavy dose of theology and philosophy. Oh, and codes:

- There are codes within codes

- Some made-up codes end up being real

- Encryptions lead to new mysteries

Codes, just like puzzles, are an easy device to create tension in a story. Almost no novel, unless it’s an experimental one, will avoid solving a code or puzzle, so the reader can always expect a solution at some point in the book.

For another book using codes as a suspense device, look no further than Agatha Christie’s last book before she died, “Postern of Fate.”

In this book she has a detective couple move into a house filled with books. One of those books has a mysterious coded message in it, and you’ll never guess — the detectives must unravel the code to solve the mystery.

21. Illness as Suspense Device

A serious illness always creates suspense in a novel. Will the character survive or won’t they?

Look at John Green’s “The Fault in our Stars,” where we have cancer-ridden teenagers in love.

The question the reader wonders: who will die first? So the reader follows those bread crumbs of suspense until the death at the end.

The same principle holds for irreversible diseases like Alzheimer’s, such as in Jonathan Franzen’s “The Corrections.” Perhaps we’re not wondering whether the grandfather will recover, but we are feverishly reading to see what happens to him.

22. The Promise

A foundational Bookfox principle is that you can learn from all genres of storytelling. There’s no need to be snooty. In that broad-minded spirit, here is advice from the sophisticated storytelling of John Wick II. Keanu Reeves gives a serious promise at the end of the film:

“Whoever comes, whoever it is, I’ll kill them. I’ll kill them all.”

Where is the suspense in this line of dialogue?

Well, we’re not wondering if he will kill them. The premise of John Wick is that he’s an unstoppable killing machine, capable of cutting down legions of enemies even if he’s only armed with a pencil.

The suspense is how he will kill them. And of course all three of the movies deliver on this promise, showing death arrive from everything from a horse kick to a book bludgeoning.

In a slightly more classic vein, Edmond Dantès in “The Count of Monte Cristo,” also makes a vow for revenge. This is one of the greatest revenge novels of all time, and Dantès promises to:

“punish the wicked.”

Whatever violence a character promises, we want to see that promise fulfilled.

23. Create a Mysterious Identity

People are at the heart of all suspense, and an unknown identity always piques the reader’s interest. For the reader, that’s a tension that won’t be resolved until they know the identity.

In Roberto Bolano’s “2666,” there’s a reclusive German novelist named Benno von Archimboldi. Even though he’s one of the most famous writers in the world:

- No one knows his true identity.

- No one knows anything about his background

- No one ever know what he looks like (no photos)

So a group of scholars go on an international hunt to figure out Benno’s true identity. It’s a mystery woven throughout all five of the books that make up 2666: a hunt for this elusive author.

In Orhan Pamuk’s murder mystery “My Name is Red,” we actually hear firsthand from the murderer in some chapters, but he speaks directly to the reader without revealing his identity.

So the reader is constantly trying to piece together clues from what he’s telling us to figure out who he is.

24. Emphasize the Unknown

When the reader encounters the truly alien, the out-of-this-world, the beyond-comprehension, that creates automatic suspense. We have no idea what to expect as readers.

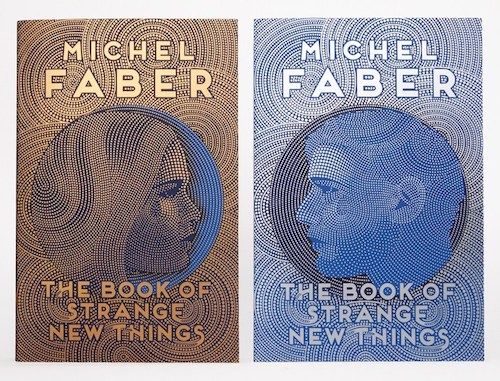

Look at how Michel Faber creates suspense in “The Book of Strange New Things,” where a missionary goes to a new planet to evangelize the aliens.

We feel suspense about:

- What are the aliens like?

- Will the missionary survive being light years away from his wife?

- Will the friction between humans on the new planet boil over?

This isn’t a book with edge-of-the-seat moments, it’s a slow burn that stokes curiosity. Suspense, in its most basic and mundane form, is often nothing more than curiosity about how the story will unfold.

25. Create Suspense in a Title

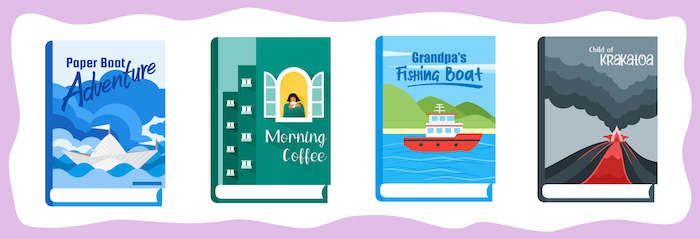

Look at the image above. Which of the four book titles create the most suspense?

This point about your book title is last because it seems stupidly obvious. Obvious — but also genius, and a brilliant way to set up reader expectations.

This way, the reader will feel suspense even before they start reading.

Look at “My Sister, the Serial Killer,” by Oyinkan Braithwaite. The reader begins the book already looking and waiting for that first murder, the second murder, the third murder.

Or “Chronicle of a Death Foretold” by Gabriel Garcia Marquez. The reader already knows there will be a death, and is on tenterhooks waiting for it finally to be revealed.

If you can choose a title which reveals a tense point of the plot, don’t be afraid to give it away. Readers become more curious, not less curious, when you reveal a crucial aspect of the plot. You might not surprise them with what happens, but you’ll surprise them with how it happens.

Oh, and as far as most suspenseful title in the four book titles in the image? If you guessed “Child of Krakatoa” creates the most suspense, you’re right.

If you have a favorite example of suspense, whether in a book or a movie, I’d love to hear it in the comments.

3 comments

John,

Thanks again for your research, wisdom and willingness to share.

Townsend

It’s quite true nothing is new and probably Shakespeare knew how to create suspense long before we ever did, and not only in his tragedies but also in his comedies- just an example, “In All’s Well that Ends Well,” don’t we want to read until the end if Helena gets her man or not against all odds? Today we have a genre for that called “Romance”, but the suspense is no different.

Thank you for all the insight. As I was reading I began writing my next small series of books. You inspired me.