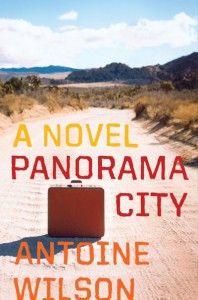

Antoine Wilson, author of the newly released novel Panorama City, was gracious enough to answer interview questions via email for BookFox. Wilson’s previous novel “The Interloper” was fantastic, and he is a sterling member of the Los Angeles literary community, in addition to being a really nice guy (at least at the literary parties where I’ve seen him!)

Antoine Wilson, author of the newly released novel Panorama City, was gracious enough to answer interview questions via email for BookFox. Wilson’s previous novel “The Interloper” was fantastic, and he is a sterling member of the Los Angeles literary community, in addition to being a really nice guy (at least at the literary parties where I’ve seen him!)

BookFox: Oppen Porter makes an art out of optimism, folksy wisdom, and comma splices. How did you develop his voice?

Antoine Wilson: It’s funny—I’ve heard this question about voice several times now, and I’m never sure how to answer it. I don’t know exactly what voice means. It seems to cover everything you mention, from an entire worldview to a character’s diction to intentionally corrupted grammar in service of a “spoken” feel. As you can imagine, trying to source all of that after the fact feels futile.

As a writer, I’m hesitant to answer for what I’ve done, for two reasons: 1. The process itself is so mysterious (it feels frustrating, mainly, while it’s happening, but ends up being mysterious); and 2. I can’t remember how anything gets developed. All I have is a pile of notes, a series of drafts, a bunch of files on my computer. I suppose I could go back, forensically, and try to understand my own process, but I don’t think that would do anyone any good, least of all me.

All that aside, the worldview comes from my own optimism blended with various aspects of Don Quixote; the folksy wisdom comes from a love for aphorism blended with Candide, and the language itself is an approximation of local speech blended with the thought-spirals-in-text of the Austrian novelist Thomas Bernhard. The process was one of writing and discarding a series of first drafts, increasing in length until I had a novel. Probably four complete and unique drafts up to about a hundred pages before I sorted it out. Please note that if I could do it any other way, I would.

This book has a classic, archetypal structure—small town man moves to big city. Were there any models you used for the novel?

Definitely Candide, though Voltaire is much crueler to his characters. And at times, especially when he’s with Paul Renfro, I thought of Oppen as a sort of Californian Sancho Panza. Filmically, small man comes to big city is a rich tradition. The Jerk is a favorite film of mine, and I have to fess up to conceiving of this novel (after the fact) as The Jerk meets Marilynne Robinson’s Gilead. (One time in a radio interview in 2007 I mentioned Crocodile Dundee, but I take that back now.)

I believe that one of the functions of art, as such, is to help us see our world with new eyes. I was attracted to the idea of depicting the world of Los Angeles, or the San Fernando Valley at least, through the eyes of an illiterate naif, to seeing what would happen if I stripped away my own kneejerk judgments and the distracting info-blast of signs and written language.

Using your distinction between “man of the world” and “provincial order medicine online india man,” how do you think writers have tried too hard to be a skewed version of “man of the world”?

Using your distinction between “man of the world” and “provincial order medicine online india man,” how do you think writers have tried too hard to be a skewed version of “man of the world”?

You can travel the world and not see a thing, depending on what’s in your head. The distinction I make in the book covers the difference between the trappings of a kind of life, the badges, the trophies, the souvenirs, and the living of the life itself. It’s only natural that we pursue conclusions to our experiences, and that we memorialize those conclusions; nevertheless, we can begin to mistake the slide show for the vacation itself, if you catch my drift.

As for writers, I’m not sure what to say. Some of them are provincial beyond belief, even if their province is so-called “literary culture.” Others are plenty worldly, even if they write almost exclusively about Eastern Ontario. Some are careerist to the point of oddity. Some are all about the work. In the end, it doesn’t really matter what writers are trying to be—it all comes down to what’s on the page.

I remember a video you posted on “How to Write a Novel,” and it was essentially a accelerated video of you at your desk, writing, with a voiceover that said “Do this for, maybe, 3 – 4 hours a day, for 2 – 3 years.” The simplicity of it was hilarious. Do you think writers work too hard to find secret, magical advice when the most important advice is laughably simple?

Not in my experience. Whatever works, works. And I’d never call it laughably simple, though my video is obviously intended to evoke a laugh. Simple advice is after all the toughest to absorb, because on first glance it seems self-evident. It doesn’t nick you until you’ve actually had the experience, at which point (too late) you can finally say, “fuck, that was deeeeeep.”

You love to surf. How does surfing feed your writing?

The short answer is that surfing feeds my life in a way that allows me to continue writing, as opposed to collapsing in a puddle of neurotic goo. The slightly longer answer is in Poets & Writers magazine.

What is the film or auteur that has affected your writing the most? How has the medium of film altered prose in the last fifty years?

Kurosawa. His film Dodes’ka-den, in particular. As for film’s influence on prose, I’m no expert, but I feel like certain jump-cut type techniques have influenced the way stories get written. Plus, lots of people talk about writing books in terms of “scenes.” Far too many books these days read like the treatments for the films they will eventually spawn. On the other hand, other books have made great advances in depicting consciousness in ways that film can’t touch. The language of books is closer to the language of thoughts, after all…

Name an author who’s under-read and why you like him or her.

Maile Chapman. Her novel is called “Your Presence is Requested at Suvanto.” She’s brilliant, her language is insanely precise and evocative, and there’s something consistently magical and mysterious about her work.