Some writers hate outlining while others think it’s a godsend.

Some writers hate outlining while others think it’s a godsend.

Which kind of writer are you? And have you tried the other side?

Those who are against outlining usually say they enjoy the discovery process they experience as the story unfolds. They learn more about their story, their characters and their own selves as a result of experiencing the world they are creating moment by moment.

Writers who like outlines usually believe that habit and structure make their story telling fluid, easier to write and precise. They believe they write better when they have a structure to follow, rather than improvising every day.

Pick the Outlining Process That Works for You

There are many successful writers who subscribe to both camps of outlining beliefs. But ultimately, it seems like they all have some sort of pattern they stick to that words for them.

- J.K. Rowling’s outline was a spread sheet written by hand on lined paper with blue pen. Not necessarily the most fancy outline in the world.

- Henry Miller literally drew a map for his outline for “Tropic of Capricorn.”

- William Faulkner wrote his outlines on his walls.

Literally no rules.

The point is not the outlining, the point is the story. Your form of organization, or creating a sort of timeline for your story, should excite and inspire you.

Why You Think You Shouldn’t Outline:

Now, “outline” can be a scary word. Steven James, author of the critically acclaimed eight part series “Bowers Files,” says, “When I was in school and a teacher would assign us to write an outline for a story, I’d finish the story first, then go back and write the outline so I’d have something to turn in. Even as a teenager I thought outlining was counterintuitive.”

Outlines got their stigma from those high school days when you had to create the most boring, non-inspiring type of outlines one can make. It seemed like the least exciting part of writing a paper and as Steven James brings to light, it is often not used the right way.

Learn How Other Creatives Outline:

I had the privilege of seeing artist Maria Pavlovska, who has a studio at Mana Contemporary in Jersey City, and her creation process. It was inspiring. She created an actual wall size diagram out of black construction paper. Inside of one big square on the wall, there were lots of boxes and inside of each box was a section of the painting that would later be synthesized with all of the other boxes to complete the entire painting. Inside of each individual box there were black lines creating more sections so that even that sectioned off part of the painting was broken down. With this version she was able to look at what she was creating and then change, replace or remove what didn’t work. Then she created a second, smaller version of that outline that was a little more finalized and finally, she created the masterpiece.

Gary Lichtenstein, who has been publishing with Richard Meier for the past five years and has worked with other giants in the art world, is a publisher and printer of limited fine art silkscreen editions. He creates silkscreen collages with hand embellishments on both paper and canvas. I had the privilege of meeting him briefly, walking through his studio and observing one of his apprentices as they completed a silkscreen edition. I walked in on the middle of his outlining process. He explained to me that first he grabs the papers he wants to use and begins designing his idea. Then he begins to make many versions until he creates the one he likes. He essentially outlines what he wants until he comes to a place where he feels he has created what his soul wants to communicate.

Outlining is not uncreative, it’s a process. It is both a right and left brain activity.

The goal is that you will be able to find an outline that caters to and is serviced by both your right and left brain.

Key Points to Remember Before You Outline:

- Once you find your way, or even as you find your way, habit is key. As creatives we want to do what feels right and what inspires us, and that’s okay. But it’s also extremely necessary to get into a rhythm. When you commit to your routine, inspiration will come in two forms: when you’re not expecting it and when you’ve made time for it.

- In her book “90 Days to Your Novel” Author Sarah Domet makes the point that, “Outlines change. People change. Plots change. Even change changes.” It’s okay to let go of the idea that creating structure for yourself is going to stunt your work or box you up.

- Just like a recipe, your outline is a grid of suggestions, an idea of where you want to go and why. Domet says, “Recipes guide us – but the creativity still belongs to the chief.”

- To start building your story, and in each scene, you need to establish:

- Setting: Where does this scene take place?

- Character: Who are the characters participating in this scene?

- Plot: What is this scene about?

- Contribution: How does this scene contribute to the overarching theme of the story?

- When you are writing a story, you need:

- A crisis or change in your character’s life.

- Tension.

- A satisfying climax and ending. (Lindsey Duran has some great words to share about good endings.)

- It’s okay to chase new stories within your story. Give yourself the creative liberty to “waste some time” on a new idea you might have.

5 Methods of Outlining

1. The Good Old Fashion Way

Remember back in high school when your teacher made you outline every essay, every paper and every research project? You’d use Roman numerals to state what the introduction would be, what the body would be and finally what the conclusion would be. It looks something like this:

I. Intro will be about … Blah

II. Blah and then Blah

III. Finally… Blah

It may bring back some high school PTSD but it can still come in handy and is probably the most thorough and well structured outline.

- In your first Roman numeral, title the scene. Then write down the setting and the characters involved.

- In the following uppercase letters, write what your character is doing. List any explanation you feel necessary to help build the story. This is where you will establish the plot.

- In the subsequent lowercase Roman numerals include as much information as you’d like from dialogue between characters to thoughts to physical actions.

- Then skip a line and explain how this scene contributes to the overarching point of the story. Every scene must inform the plot and bring you closer to a satisfying conclusion of your story.

Be as descriptive or as vague as desired.

Example:

I. Copper’s Day at the Beach

Setting: Margarita and Copper the puppy go to Huntington beach in California.

Characters: Margarita and Copper.

A. Margarita and Copper are in the car driving to the beach. Margarita is happy to finally get a day off of work to spend with her puppy.

i. “Are you excited to go to the beach Copper?”

ii. Copper stands on all four on the passenger’s seat, tongue out smiling, waving his tail, eyes wide open with excitement and shakes his head up and down as though to say “yes!” He bounces over towards Margarita, standing on the center console, leans over and licks her on the cheek.

iii. “Okay! Okay Copper!” Margarita laughs. “Go back to your seat before you cause an accident.”

vi. Copper goes back to his seat and looks out the window with his tongue hanging out.

B. Margarita and Copper arrive at the beach and find parking. They get out of the car and head toward the beach.

i. “Ready Copper?” Margarita reaches for his leash and exits the car.

ii. Copper starts spinning in circles in his seat and darts out of the car, jumping up and down as Margarita attempts to clip his leash on.

iii. Margarita leans over and grabs her beach back. Sitting on top of the beach bag is Copper’s favorite yellow tennis ball. Margarita, bag in one hand and leash in the other, shuts the car door with a swing of the elbow and heads off to the beach with Copper.

C. Copper and Margarita play catch in the water.

i. Margarita throws the tennis ball in the water for Copper to go fetch. “Go get it boy!”

ii. Copper darts after the ball and returns drenched and ready to go again.

iii. After a while Copper gets cold and tired. He lifts one paw up indicating that he is done.

vi. “Are you ready to relax my boy?” Copper stares back. “Alright little guy. Lets go get warm.”

v. Margarita and Copper lay on a towel side by side and get warm under the sun.

There is a lot of detail and a lot of dialogue in this version. Not all of the detail is there but there’s enough to get the ball rolling.

2. The General

If you’re a person who likes to unpack and discover during the drafting process, this form of outlining will only ask you to lay out the general idea for the timeline of your story.

- Write the scene number.

- Then title the scene, identifying the action that is taking place in the scene. You can also identify whether the scene is taking place inside or outside.

- Define the setting.

- Define who the characters are.

- Define the plot.

- Define how this scene contributes to the rest of the story.

Example:

Scene 2: Work Promotion/Interior

Setting: In Margarita’s boss’s office.

Characters: Margarita and her boss

Plot: Margarita’s boss calls her into his office. He offers her a promotion to become one of the head curators at their company’s art gallery in France, one of the most prestigious art galleries in the world. This is the opportunity of a life time for Margarita. She must now chose between love and her career.

Contribution: This life change in Margarita’s life is the cause of the tension that will rise in the future.

Scene 3: Confrontation/Interior

Setting: In Margarita’s apartment.

Characters: Margarita, Copper and Jake

Plot: Margarita is preparing a romantic candle lit dinner for herself and Jake as Copper follows her around. Jake has not arrived yet. As Margarita is running around cooking and preparing things, Copper is talking to her, in his mind, a voice not audible to Margarita, about how much fun he had at the beach. As Copper is chatting with Margarita, unbeknownst to her, she is also talking to Copper, in a voice audible to both Copper and herself, about breaking the news to Jake that she is going over seas next month. Copper believes she is responding to him, believing she can hear him, and thinks that Margarita is talking about going to the beach next month and not that she will be moving to the other side of the world. Jake arrives and the three of them sit down for dinner. Copper has his own chair at the table even though he is not eating. Margarita breaks the news to Jake and Copper looks over at Jake excitedly. Jake is saddened and upset which leaves Copper confused. He invites Jake to go to the beach with them next month, in his non audible to humans voice, and then he realizes Margarita is not talking about the beach. He realizes she is moving to the other side of the world. Both Copper and Jake are left mystified.

Contribution: This moment complicates the plot further and causes tension, confusion and sadness in Copper, Margarita and Jake.

There is no dialogue or specific details in this outline. There is no description about how Margarita set the table, what she was cooking or what Jakes actual response was. We don’t even know what any of the characters look like yet.

What is provided is the general idea of what is going on in the scene, with whom and why.

This form provides a more creative flow. I see it as a sort of journaling about your story before defining the specifics.

3. Flash Cards!

Big thanks to Favell Lee Mortimer, English author of educational books for children during the 1800s, who helped pioneer the flashcard invention! What she didn’t know was that authors would some day use her system for more than just phonics.

This is not only one of the easiest outlines, but its also rather exciting. You can carry your cards around with you anywhere you’d like and you can experiment with reorganizing scenes easily.

A professor of mine once encouraged me to play a game with my story. We were discussing structure.

He explained that an essay is a collection of paragraphs (or in this case a story is a collection of scenes). Each paragraph/scene is a building block that should be essential to the story. What does it say and do to contribute to the overall picture? If someone were to take the scenes apart, they should be able to put it back together in the order that you had it in, like a puzzle.

He told me to grab all of my scenes, scatter them up and see if I can piece it together again. If I can, it probably means that my story makes sense and can be followed. If it doesn’t, I’ll know which pieces need to be re-worked on, moved around or discarded.

When I heard about the flashcard technique, I immediately imagined throwing all of my flashcard scenes on the floor. It’s a fun exercise that helps you easily outline your story and see how well it fits together.

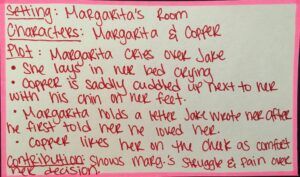

- In a few short words, describe the setting and name the characters.

- Then create a title that encompasses what the plot of this scene is and give a few bullet points that offer more insight.

- Finally, briefly explain how it contributes to the story.

Example:

*Use colored flashcards at your discretion ;)*

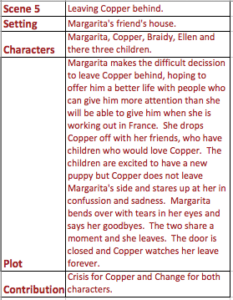

4. On A Table

Use Microsoft Excel or your preferred spreadsheet style.

You can easily insert and delete columns and rows electronically and can be as concise as Flash Cards! or as descriptive as The Good Old Fashion Way. Entirely up to you.

Though you cannot throw this version all over the floor and make a fun mess like you can with Flash Cards!, you can still easily reorganize the columns and rows.

- Write “scene number” in the first column/row.

- Then write the scene title in the column to the right of it (1st row).

- On C1 R2 write in “setting” and explain the setting in the column to the right of it (C2 R2).

- Continue in this manner typing character, plot summary and finally contribution.

Example:

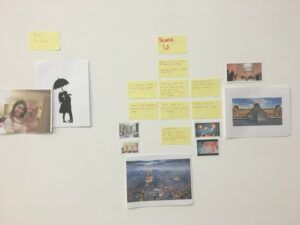

5. The Wall

Turn on some music and get messy! Start posting your scenes up on your wall using note cards, inspiring pictures, drawings, magazines, newspapers and whatever else your heart desires. Post them in chronological order or in whatever order inspires you most. If it’s not in order right now, that’s okay. The point is to define each scene with as many pictures and clippings to give you a good idea of what that scene will be about.

- Start by creating a section on the wall, whiteboard or bulletin board dedicated to inspirational pictures, clippings and writings that inform your over all story. Then create a section for one scene and one scene only. Everything gets it’s own space, establishing the organized mess.

- In each scene section use notecards, post-it notes or a taped piece of paper (literally no rules on what you chose to write on)

- Post up your setting (include pictures that inspire you around this area)

- Then your characters (maybe some pictures of what you think they look like)

- Some phrases that inform the plot (really anything you want to post up from dialogue to character thoughts to plot description)

- And finally what it has to do with the overall theme.

There is an incredible amount of detail that goes into this formula but there is also total freedom in what you add and how you add it.

Example:

This will be a visual experience. The picture and short phrases that give way to your setting, characters and plot will wake up your senses and inspire your mind.

This is a great example of an outline that is inspired by your right brain. After this, you could jump to a more formal outline where you’re left brain has the chance to fill in the gaps, analyze and ask necessary questions.

What you must remember is that each writer and individual is different. Discover what your method is and rely on that.

Outlining might sound like a waist of time or an inspirationless pursuit but I’m of the mindset Dwight D. Eisenhower was of when he said, “In preparing for battle, I have always found that plans are useless, but planning is indispensable.”

Or as my friend says, “outlines are worthless but outlining is essential.”