I love short sentences. I really do. In any book filled with a series of long, expansive sentences, a short sentence arrives like a gift.

I love short sentences. I really do. In any book filled with a series of long, expansive sentences, a short sentence arrives like a gift.

Short sentences rarely have the ambiguity or mystery of a long sentence. They rarely have twists or swerves or switchbacks, because that requires the length of a longer sentence. They rarely win your admiration for verbal virtuosity, the way that a long sentence can astonish you.

What is the effect of short sentences? The effect is violence. A short sentence can gut punch you. They can deliver a surprise with the utmost efficiency. They can usher in a fantastic plot revelation with a deft flick of a few syllables. They have a power due to their brevity, and they have agility because they have nothing to weigh them down.

It would be a mistake to call a short sentence a simple sentence. Although many short sentences are simple in that they’re not compound or complex or compound/complex, they’re not simple meaning a childish thought, or one easy to comprehend. The short sentence can have a complex idea. It can deliver a sophisticated or challenging concept.

Although I dimly remember the gist of lengthy sentences, it’s the short sentences that I quote. About half of the examples below I remembered from memory.

If you want a short sentence definition, it’s impossible to give a limit. Is it defined by word count or letter count? These things don’t matter. A short sentence is not under 7 words or under 20 syllables. You recognize a short sentence when you see one. And the short sentence is also defined by its surroundings: a sentence might not be short when surrounded by ten-word sentences, but when surrounded by 100-word sentences, it seems like a dwarf.

If you’re like me, you want to write short sentences that make the reader stop and reread them, make them ponder them late at night, make them quote to their friends. So let’s get started. This list of beautiful short sentence examples should help you write sentences that stun and dazzle.

1. Change Registers

David Foster Wallace uses a short sentence to provide the sole commentary in a piece otherwise filled with description and details. His short story Incarnations of Burned Children — about a horrifying moment when a pan of boiling water falls on a child — is only 3 pages, but it’s full of sentences topping the 100-word mark. After the longest sentence of the piece, a 232-word monster, he follows it with a 10-word sentence:

“If you’ve never wept and want to, have a child.”

Not only is there difference in length, but in the type of content. All the other sentences offer no grand insights, no wisdom from above, no overarching commentary. They only relate the strict details of what’s happening, while this short sentence offers the only distant observation of the piece. It’s one of the most devastating sentences I have ever read.

2. Shock with Contrast

In Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian, the most repeated phrase is “They rode on,” which is often a stand-alone sentence. Given McCarthy’s leanings toward the super-long sentence connected by “and” (a technique called Polysyndeton), these 3 word sentences crack like a rifle shot.

Check out how he sandwiches this brief phrase between several much longer sentences:

“They cut the throats of the packanimals and jerked and divided the meat and they traveled under the cape of the wild mountains upon a broad soda plain with dry thunder to the south and rumors of light. Under a gibbous moon horse and rider spanceled to their shadows on the snowblue ground and in each flare of lightning as the storm advanced those selfsame forms rearing with a terrible redundancy behind them like some third aspect of their presence hammered out black and wild upon the naked grounds. They rode on. They rode like men invested with a purpose whose origins were antecedent to them, like blood legatees of an order both imperative and remote. For although each man among them was discrete unto himself, conjoined they made a thing that had not been before and in that communal soul were wastes hardly reckonable more than those whited regions on old maps where monsters do live and where there is nothing other of the known world save conjectural winds.”

Roy Peter Clark says, “In the land of 40-word sentences, the 20-word sentence bears a special power.” In this case, in the land of 80-word sentences, the 3-word sentence is king.

3. Change the Voice

In Clockwork Orange, the ultra-violent Alex has to undergoes some crazy behavioral modification from the state. Of course the whole book is filled with made-up language, which makes it a thrill to read, but this simple sentence that ends the paragraph (and a whole chapter) doesn’t play with language at all. It’s different from other sentences not only by length, but also by normal language. Both those differences make the last sentence stop hard:

“Oh, it was gorgeosity and yumyumyum. When it came to the Scherzo I could viddy myself very clear running and running on like very light and mysterious nogas, carving the whole litso of the creeching world with my cut-throat britva. And there was the slow movement and the lovely last singing movement still to come. I was cured all right.“

Compare the plainness of that last line to the previous words like gorgeosity, viddy, nogas, litso and britva. It’s so normal that it’s fantastical!

4. Create a Funnel Shape

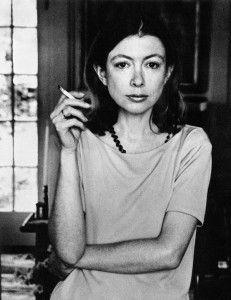

Joan Didion is a master of tightly wound sentences, coiled and ready to spring. In the essay, “On Going Home” she writes about the friction of visiting her parents with her husband, and all the small ways her husband is at odds with her family:

“My brother does not understand my husband’s inability to perceive the advantage in the rather common real-estate transaction known as “sale-leaseback,” and my husband in turn does not understand why so many of the people he hears about in my father’s house have recently been committed to mental hospitals or booked on drunk-driving charges. Nor does he understand that when we talk about sale-leasebacks and right-of-way condemnations we are talking in code about things we like best, the yellow fields and the cotton-woods and the rivers rising and falling and the mountain roads closing when the heavy snow comes in. We miss each other’s points, have another drink and regard the fire. My brother refers to my husband, in his presence, as “Joan’s husband.” Marriage is the classic betrayal.“

What I love about this paragraph is that it’s shaped like a funnel. If we include the sentence just before this quote, we have six sentences, and each of the six sentences grows shorter and shorter.

- 104 words

- 57 words

- 50 words

- 12 words

- 12 words

- 5 words

Six sentences, the first longest and each one afterwards a little shorter, until we culminate in the final, shortest sentence, a five-word bombshell that describes the totality of everything that comes before it. It’s the perfect way to end a paragraph. The shape of the whole paragraph directs you toward the end. Even if the paragraph indentations were stripped away, readers would know they had reached the end of a thought.

5. Sign off with Brevity

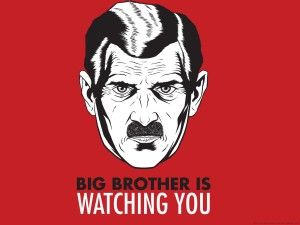

George Orwell’s 1984 is about a man fighting the totalitarian power of a government; aka “Big Brother.” He spent his life resisting the authorities trying to make him submit. And after loads of torture and social conditioning, the novel ends with one of the most chilling lines of all time:

“He loved Big Brother.”

Could you imagine if this line was any longer? Could you imagine if George Orwell had written, “But it was all right, everything was all right, the struggle was finished, because he had won the victory over himself, since he loved Big Brother”? The wordiness diminishes the sadness. When readers get blindsided by that sparse, four-word last line, they want to cry.

6. Repeat your Short Sentence

So it goes. What a powerful three words. You get such a sense of resignation, of throwing up of hands and submitting to the forces of inevitability and fate.

So it goes. What a powerful three words. You get such a sense of resignation, of throwing up of hands and submitting to the forces of inevitability and fate.

And when Kurt Vonnegut uses that sentence again and again throughout Slaughterhouse Five, setting it against the backdrop of one of the worst tragedies of WWII — the firebombing of Dresden — the lackadaisical carefree attitude of that sentence provides a lovely contrast to the horrific facts about Dresden.

By repeating “So it goes” again and again throughout the narrative, Vonnegut is showing how incongruous that attitude is compared to Dresden, and also voicing the devil-may-care attitude of the rest of the world toward the firebombing. The phrases creates this lovely thematic unity throughout the whole book.

7. Cluster Technique

Roberto Bolano is not known for his short sentences. He’s known for the five-page sentence in 2666 totaling more than two thousand words, and for the page-long sentences of By Night in Chile.

But unlike Cormac McCarthy who sticks short sentences between his long sentence to vary the rhythms, Bolano will write a number of very short sentences right in a row, changing the whole rhythm of a paragraph. The effect of these short sentences is that the prose decelerates, as it becomes choppy. Also, the tone becomes very matter-of-fact.

Look at this example. Here three friends are visiting a painter named Johns, who cut off his hand as an act of performance art. The three friends want to know why he did it:

“Dusk had settled around Morini and Johns now. The nurse made a move as if to get up and turn on the light, but Pelletier lifted a finger to his lips and stopped her. The nurse sat down again. The nurse’s shoes were white. Pelletier’s and Espinoza’s shoes were black. Morini’s shoes were brown. John’s shoes were white and made for running long distance, on the paved streets of a city or cross-country. That was the last thing Pelletier saw, the color of the shoes and their shape and stillness, before night plunged them into the cold nothingness of the Alps.”

Four sentences in a row, all about five words. Look at how all those short sentences in a row slow down time. How the attention to small, almost peripheral details gives the scene an otherworldliness. It changes the entire atmosphere of the scene.

Check out James Salter doing the cluster technique in “A Sport and a Pastime“:

“They are waiting on the street in the late afternoon. The air is thin as paper. The day is raw.”

For some reason I see the triple-short sentence as the most popular variety of this form. Usually it’s a Sentence-Verb-Object sentence (SVO), an order that seems to underscore the simplicity. As a reader, it really makes you measure the words and pace your reading.

8. Reveal Character

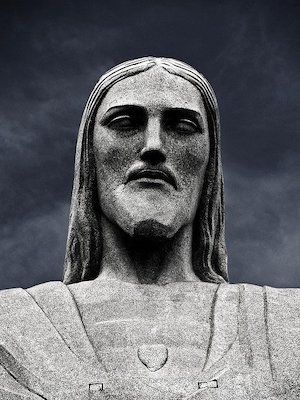

Quiz time: Do you know the shortest sentence in all of the Bible?

Quiz time: Do you know the shortest sentence in all of the Bible?

I’ll give you a Sunday-School hint: It’s about Jesus.

Kudos if you guessed it:

“Jesus wept.”

That’s right — two words. This is a fantastic sentence not because of rhythms, or because of contrast with longer sentences around it, but because how much is accomplished with only two words. Here we have a prophet that the disciples will proclaim is God embodied in flesh, and yet when he meets up with the death of his friend Lazarus, he breaks down. He weeps. In only two words, this is the best example of the humanity of the God/man. We see Jesus humbled, broken, teary. It’s difficult to characterize anyone well in a single sentence, but these two words add so much to the persona of Jesus, it’s practically a miracle in itself.

9. Open your Novel

There are so many famous examples it’s difficult to choose. In fact, I won’t even attribute the first lines below, and you can probably guess most of them:

- Call me Ishmael.

- The old man was dreaming about the lions.

- Lolita, light of my life, fire of my loins.

- All this happened, more or less.

- I am an invisible man.

- A screaming comes across the sky.

Why is it so powerful to start a book with a short sentence? The reader enters the world you’ve created without any delay or apprehension. By the time that first period closes over them, they’ve already succumbed to your charms. It’s too late to turn back.

There is no way to abandon reading a sentence this short. And it carries an awesome load of responsibilities upon the remarkably frail shoulders of a few words — establishing the tone, the style, the setting, the conflict.

That’s why Gabriel Garcia Marquez said that he used to spend months trying to get the first sentence right, but when he did, the rest of the book fell into place.

If you want to improve your sentence-writing skills, check out this online course. Learn things like:

- the 2/3/1 rule, leaning/standalone rule

- how to break free of common sentence guidelines

- The tricks and techniques to make a beautiful sentence

21 comments

I adore what short sentences can do — hopefully this will inspire many writers!

I’ve read it all, first to last paragraph – I rarely do that. Beautiful writing, easy to read.

Hmm. None of your examples consist of just short sentences.

Your message seems to be — ‘use them sparingly’.

That’s good advice. But in your omission, perhaps you’re giving the wrong impression. Plenty of writers keep sentences short consistently. Others use long sentences only occasionally, in an inverse model to the ones you describe above.

As a challenge, try keeping sentences short throughout a piece. It’s not easy. But your readability will skyrocket. Readability is profoundly important in business communication and advertising.

You’re right that I tend to concentrate on contrast, but I think #7, the cluster technique, is about writing a bunch of short sentences in a row. The danger of too many short sentences in a row is that the paragraph loses its rhythm, since the repetition and lack of variation ends up being monotonous.

In reference to point eight, one of my favorite writing techniques for short sentences is six-word story writings. They have helped me tremendously in creating short, powerful sentences.

Agreed! Those are a fantastic way to exercise your micro-fiction writing skills, and your short sentence skills.

Loved this, John! I quoted you in a recent blog: https://askriverbed.wordpress.com/2016/07/19/the-girl-from-ipanema/

Hope it brings you many more readers!! Cheers, Sharon

Thank you so much! That’s some great advice for writers.

Nice post. When I began writing, I got into alot of trouble with the semi-colon. Almost every sentence of mine had one. Although I had used it correctly, demonstrating what I thought was great command of it was actually out of control with it. I checked into semi-colon anonymous, and now, instead of inserting a semi-colon, I break up the sentence and trade the semi-colon in for a period. No more compound complex sentences. Simple sentences will keep your writing honest.

If there is one writer I know who uses the semi-colon correctly, it is the mystery novelist Carl Hiaasen.

Wonderful.

this is great work, thanks 🙂

what is a d/f b/w long sentence and short sentence in a business communication/practical language.

I’m always delighted to see your emails in my inbox; full of useful content but lighthearted and entertaining. This idea wasn’t completely new, but fleshed out in perfect detail. I’m grateful for your words. Brilliant.

(Did I do it? Word funnel, ending with super short sentence?)

Ha ha, well done! And very glad you liked the piece. Happy writing!

Thank you so much.

Your words about Jesus almost made me cry. I’ve never imagined anyone speaking as you did about so simple a deed in scripture and yet, you did. You nailed it.

Thanks.

I so appreciate your continued guidance, and I love receiving your emails, but please reconsider linking things to Amazon. Link to an indie bookstore instead. Link to Bookshop.org or similar.

The shortest complete sentence I recognize is one my parents often found it necessary to use to control my behavior. One word. NO

A profoundly complex juxtaposition of an idea is posed in the question “To be or not to be?”

The world would be a better place with more short sentences.

Hope you’re having a glorious day. You made mine. Thanks.

It’s a lot.Take thank you.