It’s not as easy as you’d think to write in first person.

It’s not as easy as you’d think to write in first person.

Although it seems natural to speak in the voice of a single character, since you’ve practiced all your life, there are some tricks to learn and pitfalls to avoid.

For instance, there isn’t only one kind of first person writing. There are actually four different ways to do first person point of view! (We’ll break down those types later).

Historically speaking, most books pre-1900 were written in the third person (with some notable exceptions). Now, if you look at the last five years of prizes like the Pulitzer, the National Book Award, the National Book Critics Circle Award, and the Man Booker, you’ll find about 30% of the finalists are written in the first person. If you look at genre and commercial fiction, you’ll find the percentage is even higher, at about 50%.

Which means that the first person POV has fully come into its own in the modern era. So celebrate the future by writing in first person! You’re part of a sweep of history that prizes the intimacy of a single voice, a single voice against the multitudes.

Now let’s figure out how to write in first person.

4 Tricks for Writing in First Person

1. Show Some Attitude

Attitude is what literary agents call “voice driven.” Your characters need to be snarky, or witty, or funny, or droll.

Nothing is more dull than a first person narrator who speaks like a computer on the page. The more personality you can infuse into your narrator, the more fun the reader will have.

Which first person narrator is better?

1. “I went into the bar and decided to ask the bartender for a drink. Even though the bar was closed, the bartender was able to pour me a beer. I tried to read the newspaper but it was all the same stuff I read every day.”

2. “What about a teakettle? What if the spout opened and closed when the steam came out, so it would become a mouth, and it could whistle pretty melodies, or do Shakespeare, or just crack up with me? I could invent a teakettle that reads in Dad’s voice, so I could fall asleep, or maybe a set of kettles that sings the chorus of “Yellow Submarine,” which is a song by the Beatles, who I love.”

The first one isn’t terrible, but it’s not great either. It’s straightforward, like Hemingway. This is the voice of a private eye or a recent divorcee or some other hardscrabble character. But it doesn’t tell you very much about the character through the voice alone.

The second one is the opening to “Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close” by Jonathan Safran Foer, and as Joyce Carol Oates noted, it has the most elusive and best quality of writing: energy. If you can put your energy on the page, readers will keep reading to soak up that energy.

The second one is the opening to “Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close” by Jonathan Safran Foer, and as Joyce Carol Oates noted, it has the most elusive and best quality of writing: energy. If you can put your energy on the page, readers will keep reading to soak up that energy.

Your characters need personality, and that personality should be embedded in every sentence of your manuscript. It should especially come through in the dialogue, where you have a wonderful opportunity to fly your character’s freak flag (do they speak in dialect? What’s their catch phrase or filler words?).

Advice: Start a manuscript in first person when you hear a voice talking inside your head. I mean actually hear, like a gravelly timbre of a truck driver or the screech of an elderly woman or the plaintive innocent bleat of a child. The voice will be the voice of your character, and it will be telling you a story verbatim.

2. Highlight Your Character’s Self-Deception

One of the most beautiful things about writing in the first person is that your narrator has a blind spot. Maybe even a few blind spots.

One of the most beautiful things about writing in the first person is that your narrator has a blind spot. Maybe even a few blind spots.

For instance, they could believe that they’re Casanova or Helena of Troy, but we’ll see, as person after person in bars turns them down, that their self-perception is incorrect. They could believe they’re amazing at their job as a detective, but after they bumble one case after another, we the readers understand that they’re terrible.

Three Examples:

In J.M. Coetzee’s “Disgrace,” we can see that the narrating professor David Lurie is sexually exploiting his young college student, even though he defends his action and believes he has done nothing wrong. Later on in the story, we see the underlying tension is that the professor is racist, even though he doesn’t believe himself to be racist.

In “The Remains of the Day” by Kazuo Ishiguro, a butler uses high language and formal manners to hide from everyone, including himself, that he’s in love, even though the reader recognizes it at once.

Ignatius J. Reilly in “A Confederacy of Dunces” believes himself to be of high moral standing, intelligent, and brave. The reader knows he is none of these.

If you can help the reader understand that the character lacks self-knowledge, it’ll create tension between what the reader knows and what the character knows, and the reader will keep reading to see if the character ever arrives at self-discovery. Every writing teacher talks about creating tension through the drama of plot and conflict between characters, but this creating of conflict between the reader and the character– the technical literary term is called Dramatic Irony — is one of the most underrated ways of creating tension in a manuscript.

In third person narrating the dramatic irony comes from a character not knowing that someone behind the door is about to jump out with a knife (but the reader knows), while in first person the dramatic irony comes from the audience realizing something about the character that the character doesn’t realize herself.

The more blind spots you can give your narrator, the more the audience will be invested in the complexity of the character.

Danger: If you have your narrator have too many blind spots, they’ll come off as naive or half-witted, which will sabotage the reader’s respect for them.

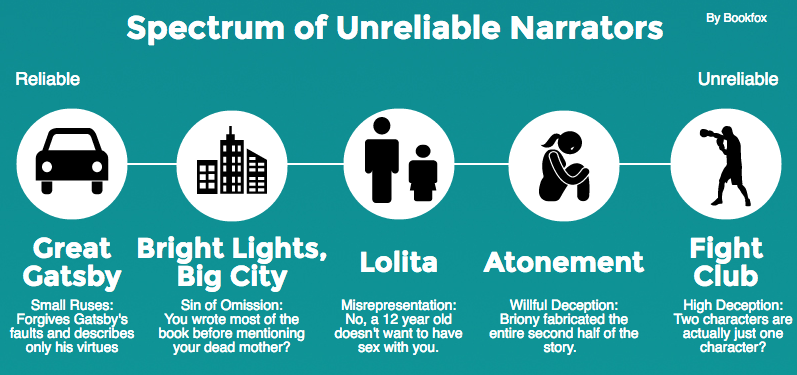

3. Figure Out Your Narrator’s Level of Unreliability

It’s not a choice between writing a first person reliable narrator or an unreliable narrator. That’s far too easy.

The truth is that every first person narrator is unreliable to some extent. Your decision as an author is where to place them on that spectrum.

Does your character only lie in small, understandable ways, like believing they didn’t mean to be mean to someone they hated? This is routine self-deception, and virtually every character will have this to some extent.

Or does your character fundamentally misrepresent the world, the truth, and other characters? This is pathological, and your character will be revealed as mentally unstable.

Every first person narrator is unreliable to some extent. But some are more unreliable than others. If you don’t decide as an author how much the reader will be able to trust your character, and in what part of the narrative they are lying (even if it’s a small lie, or a lie to themselves), then you’re missing one of the best parts about first person narration.

4. Shine Light on More Interesting Characters

I call this the Watson Approach. The Sherlock Holmes stories would be terrible if Sherlock Holmes were the narrator — we’d see right into his brain and all the mystery and tension would evaporate as soon as he figured out the crime.

I call this the Watson Approach. The Sherlock Holmes stories would be terrible if Sherlock Holmes were the narrator — we’d see right into his brain and all the mystery and tension would evaporate as soon as he figured out the crime.

No, it’s essential that the bumbling Watson narrates the story, because he can shine a light on the brilliance of Holmes.

Every first person narrator has the unique opportunity to direct all the attention onto another character. So what should you do? Populate your novel with eccentric weirdos, people that pop and dance when seen by your narrator.

And describe all these people through the unique lens of your character. What makes Watson the perfect narrator is that he’s methodical and direct. What might make your character the perfect narrator is that he keeps on describing dangerous freaks as souls full of light and goodness.

6 Dangers to Avoid

1. Reader is Trapped with One Character

By reading a first person book, your reader is essentially in an elevator with your narrator for six or eight hours. Don’t make it the most miserable elevator ride of their life.

By reading a first person book, your reader is essentially in an elevator with your narrator for six or eight hours. Don’t make it the most miserable elevator ride of their life.

First person characters have to have some redeemable characteristics, or else they’ll just be hated by a reader. Even if they have terrible faults, make them interesting faults. Alcoholism, for instance, is overused as a character fault of protagonists, especially in the hardboiled genres of detective and mystery stories. Don’t give your character cliched faults.

One last bit of advice: Populate your book with a lively cast of supporting characters, so your reader has plenty of opportunities to interact with the dialogue and actions of characters other than the central character. This will keep them from feeling claustrophobic inside the brain of your protagonist.

2. Make Sure Your Character Isn’t Just Yourself

The most important thing to remember when you’re writing first person is that you’re not yourself. Scrape away your personal voice and replace it with another person’s voice, a person you’ve created. It’s probably going to be some small part of you, but it’s not identical to you.

First person is the closest writers get to actors. You’re essentially acting when you’re writing first person. You’re pretending to be another human being, mimicking their every thought and expression and word. So feel free to invent someone!

3. Avoid Filter Words

There are some great articles out there on avoiding filter words.

Essentially, you don’t write:

I looked at the horde of political protestors racing down the street.

You write:

The horde of political protestors raced down the street.

Just cut out the action of your first person narrator looking, seeing, and acting. It’ll make the prose much more direct.

4. Too many sentences beginning with “I”

I went to the park. I saw a big duck. I loved watching all the people. I thought of how the clouds looked like anvils.

Tired yet?

Please don’t start every sentence with “I.” It feels quite redundant.

Create sentences that have an implied “I”, or talk about things other than the narrator.

Of course, don’t go to the opposite side of the spectrum and try to avoid “I” completely. After all, it is the most important word when writing first person.

5. Too many internal monologues and introspection

Get your character outside his or her head.

Quite frankly, it’s boring to read ideas after ideas, thoughts after thoughts. It’s boring to read about the main character pondering ideas better for an essay than for fiction.

Although access to a character’s head is the main strength of writing in first person, it can also turn into a liability if overused. So make sure to surround thoughts and introspection with wide padding of action, dialogue, and description.

6. Difficulty of Limited POV

Sometimes writing first person can be tricky when the reader needs to know about something happening in another storyline, or in another part of the world.

But this voluntary obstruction that the writer elects to take upon himself will eventually strength the story. It’s counter-intuitive, but if you make up obstacles for yourself, you’re going to force yourself to be more creative.

So don’t look at the limited first person POV as a hinderance but rather as an opportunity or a challenge.

Types of First Person Writing:

First Person

This is the basic form of first person writing. The narrator is telling a story from their point of view.

This is the basic form of first person writing. The narrator is telling a story from their point of view.

At no point do we know something that the narrator does not know, and we do not go into the thoughts of anyone else in the story.

Plural First Person

Instead of an “I”, this story is told from the point of view of a “we” and “our.”

Instead of an “I”, this story is told from the point of view of a “we” and “our.”

Joshua Ferris’ “Then We Came to the End,”: “We were fractious and overpaid.”

From the first lines of Justin Torres’ “We the Animals“: “We wanted more. We knocked the butt ends of our forks against the table, tapped our spoons against our empty bowls; we were hungry.”

The Virgin Suicides by Jeffrey Eugenides was also told in plural first person, from the perspective of the entire town watching a family deconstruct and try to commit suicide.

Ultimately, this is a great and flexible point of view to enable you to collect the judgment of a large group of people, a collective memory of what happened, and present multiple sides of a story.

Peripheral First Person

A peripheral first person point of view means that the narrator is not the protagonist. The narrator is trying to direct the focus of the reader onto someone else.

A peripheral first person point of view means that the narrator is not the protagonist. The narrator is trying to direct the focus of the reader onto someone else.

- Nick Caraway in “The Great Gatsby”

- Ishmael in “Moby Dick”

- Adso of Melk in “The Name of the Rose”

Multiple Narrator First Person

Every chapter, the person speaking as an “I” will shift. So you can have four people all speaking in the first person, all telling their stories.

Every chapter, the person speaking as an “I” will shift. So you can have four people all speaking in the first person, all telling their stories.

But why would you choose first person for this type of technique rather than third person? The main reason is that you want the reader to be able to hear all these voices straight from the characters. The second main reason is that you want to expose the variations between the ways the multiple characters tell the same story.

For example, Judith Freeman’s “Red Water” tells the story of three different wives of the same man in Utah. Each wife gets the chance to tell their own story in her own words.

Common Questions

Can I have multiple narrators in first person?

Yes. This is called Multiple Viewpoint First Person. You get all the benefits of writing in a particular person’s voice and the intimate view inside their head, as well as the benefits of multiple perspectives.

A great example of this is Faulkner’s “As I Lay Dying,” in which many members of the Bundren clan (15 in all) tell their version of trying to transport a dead body across Mississippi.

A more modern example would be “Gone Girl.” “Gone Girl” teaches us that the two first-person narrators must compliment each other — they must disagree, or layer in more information — in order to make this multiple narrator device work.

Why should I choose first person narrative?

Two important reasons: Intimacy and Immediacy.

A first person narrator offers incredible intimacy. Some limited third person narrators accomplish this, but nothing can rival first person for access into a person’s brain.

What’s more, a first person narrator is the best advantage writing has over film. While third person narration is exactly the point of view that film uses, first person will allow you to delve deep into the characters mind in a way that film is ill equipped to do. Some films use voice-over to try to approximate the character’s thoughts, but this is widely frowned upon and often doesn’t work (except when it does: Ferris Bueller’s Day Off and Adaptation being the best examples).

The point is that first person is the only POV that will give you an edge over the dominant storytelling form of our time: film. Through the first person, you can give a direct line into human consciousness.

First person makes the reader feels confided in. The reader feels like they’re getting a special kind of access. The reader feels, for lack of a better word, loved.

And now for the second reason: Immediacy.

With third person, you are always aware of someone else telling you the story. There is a storyteller between you and the action. He did this, she did that: who is the person telling you about this “he” and “she”?

With first person, though, you are hearing it directly “from the horse’s mouth.” First person immerses the reader directly into the story. The only POV that could possibly be closer to the reader is second person, but it’s tiring to constantly read about “you” “you” “you.”

Is there a stigma around writing in the first person?

It’s true that some writers and readers are prejudiced against first person writing. They think that it’s lowbrow, employed mostly by genre writers, and that true literature is written in third person.

But that is foolishness.

Here’s a brief list of books that are in the first person:

- Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain

- To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee

- Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë

- The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald

- Moby Dick by Herman Melville

- Lolita by Vladimir Nabakov

Is that enough pedigree for you? If it isn’t, there are thousands of classic works of literature written in the first person.

Whatever stigma you imagine hanging around first person narration, erase it from your memory. First Person POV is a legitimate tool for any writer.

Additional Resources

First Person Narrative Theory

What is the difference between the narrator and the viewpoint character? Most of the time, nothing, but if the narrator is reflecting upon something that happened years before, they may now be a different person than their younger self.

7 Narrative Tips for First Person Narrators

A few of the highlights of this article: Beware of merely reporting the actions of the main character (I call this Frankenstein writing). Also, beware of describing the inner thought life of a character in shallow, repetitive or redundant terms.

Tips for Writing a First Person Narrative

“Keep the narrative simple and linear.” Not sure about the linear rule (many first person examples break that rule), but by simple I think they mean that you cannot go into many different storylines that your narrator doesn’t have access to, and neither can you explore the thoughts of many other characters.

If you’d like to watch the most thorough and awesome video ever created about point of view (including a wonderful section on writing first person), please watch this craft lecture by Justin Cronin. He gets started on point of view at the 4:00 minute mark.

31 comments

I’m trying my hand in the mystery genre, which seems to thrive on First Person POV. These are very helpful points and I know they’ll improve my writing if I apply them. Thanks for sharing your knowledge.

Helpful tips! I’m currently rewriting/editing my fiction novel which is in first person POV.

Excellent, John, and very helpful. Thank you for sharing this.

I find some books come across are sounding ‘insincere’ when written in 1st POV. Highly possible that the writing is bad itself, but do you have any advice for this?

Quick Question, if you don’t mind helping me. I’m using first person singular. Can I describe a scene in which my first person protagonist is not present? This may be a silly question, but I can’t find the answer after searching online.

No, you can’t describe anything that your first person doesn’t know, especially anything where they aren’t present. Everything is filtered through their perspective.

Correct, but I come across stories and novels with this error quite often, even by famous writers like Somerset Maugham or widely praised recent books like Washington Black.

I can go pull a number of titles from my shelves right now that can…. and do. Quite naturally.

Elizabeth Peters uses a clever technique in her Egypt novels. The main story is told by the first-person narrator Amelia Peabody, but from time to time (when necessary to describe the actions of their son Ramses out of Amelia’s presence) a chapter entitled “Excerpt from Manuscript X” will appear, describing this other material. I have seen similar uses made of police reports, newspaper articles, and other “sources” to bridge the gap between a first-person narrator and events outside of the narrator’s personal knowledge.

I am new to writing, but have read a few books…. Yes you may.

Mostly because it’s difficult to relay everything by a first person vehicle.

He/she can’t always be involved personally in every relatable event.

Think of books you’ve read. Often they dip out to view a scene. Ex: your first person is a husband and father. Say his family gets into a pivotal car accident. While he may be told a great deal about it, there are surely details you will need to relate…. some, perhaps you don’t want your guy to know or realize.

I hope that helps. It’s how I remember.

The best way to do this is by using a frame story. If a character tells the 1st-P narrator a story (and this can be a story the narrator first mentions was told to them and is not shown in dialogue) then the narrator can tell it to the reader.

At this point, the narrator actually has limited omniscience (they know that story), and the pronouns revert to he/she rather than I, so it feels like 3rd-P limited omni, but that is completely legitimate. It technically never leaves 1st-P, and never is from a different narrator.

If that story is long, you can break it up with dialogue between the narrator/MC and the character who told the MC this story (implying the scene is the second character telling the MC the story, which the MC summarizes for the reader). It works just fine.

But surely there are some books which have some parts in first person, and other sections where the character isn’t present so it switches to 3rd person? Unless you guys mean explicitly 1st person singular? What if I was telling a story with two different views? One side in first person and another from a 3rd person perspective…

That type of POV switching is very, very rare, and it’s very difficult to pull off well. It’s best to keep the whole book in third person omniscient or in first person.

Yes, too difficult for me! I’ve tried. But others do it quite well.

I think having a balance helps? And, of course…. talent (which I lack!)

Laurie R. King does this in her mystery ‘Locked Rooms’, masterfully. The first 8 chs are 1st-P from the MC, and the rest is 3rd-P limited, following her husband, Sherlock Holmes, as they solve the mystery together. There is no real jarring feeling at the switch point.

Hello-I am new to writing, could you clarify the voice between the author, narrator, and the protagonist.

Example- as the author – I am creating the story, the narrator is describing, and the protagonist is experiencing. Is that correct? It’s unclear to me.

In first person, the narrator and protagonist is the same person.

There is only a different if you’re writing in 3rd person.

I notice that I have a lot of difficulty writing in 3rd person. When I read, I prefer first person, so maybe that’s why. I have written short stories in 3rd person (mostly assignments from high school) but when I write in first person, as the author I feel closer to my characters.

It’s like when I write in first person I can almost hear their voice and they come alive in my head. I feel more in touch with their feelings and thoughts, as if I can feel their emotions. It’s easier to put myself in their shoes, and know “what would my character do right now.

Whereas when I write in third person I feel a distance between me and the character and everything feels forced. I find that my words tend to flow more smoothly, and I don’t get as stumbled with the wording as I do in 3rd. Is that weird?

Well, anyway, I’m working on a book that was originally going to be told by one character in first person. Then I had the idea to change it all and have it in 3rd with different POV. Well, I am learning that it’s just not the same.

I personally just enjoy first person more. First person is fun to write in and I feel that I am a better story teller when I write that way. So now I’m back at square one, rewriting this story AGAIN, from the one person’s first person POV. I have a great story to tell, I just have struggled in finding the write way to show this particular story.

Destiny, I can relate. I’m currently working on my first novel as well. A lot of us believe we are great storytellers: only to find out, telling the story is another venture in itself; however, it sounds like you’re on the right track.

How do I write dialogue in first person??

I think you just need to write it as if it was a normal conversation, like, the narator in first person will hear his/her voice too, so you can write like almost like a dialog in the third person. For example:

“We were taking a break, them I said:

-Hey, do you wanna to try this new app that I saw from a friend?

-Sure. – my friend says.

THis is just a random example I hope it helped.

Also, sorry for my bad english.

Do we use past-tense to introduce the character in terms of their family status or occupation which are still the same in the present? I’m writing in a first-person POV. Thank you.

Yes.

Do you have any advice to write in the third person?

How about first person present? Does writing in the present tense change anything? Also, when writing I seem to use the word “I” far too much, but don’t know how to change it. Here’s an example:

He walks over to me and pulls me off the screw I’m perched on. His hands are warm and somewhat damp. I’m stunned, to say the least. I try to fight back, but since I don’t have any legs like humans do, he doesn’t notice my flailing clock hands darting from 4:00 to 2:19 to 11:55. Like a human heart, my gears pound in abject terror.

I feel like I say the word “I” too many times, but don’t know how to cut them down. Thanks!

“He walks over to me and pulls me off the screw I’m perched on. His hands are warm and somewhat damp. It’s stunning, to say the least. Fighting back is impossible, since I don’t have any legs like humans do, and he doesn’t notice my flailing clock hands darting from 4:00 to 2:19 to 11:55. Like a human heart, my gears pound in abject terror.”

Thanks for the help! I know what POV I must write in now! Hm… but what would an Eagle think and describe a calico cat? QUESTIONS! Lol XD

Thank you for the coaching of how to write in first person. It really is going to make me a better writer for my business ethics class discussion, or replying to another persons discussion board.

I’m writing a story called Stray about a cat who’s family moves away. Is this a good idea or not? I’d love some feedback!

Thank you for all the good information, but I’m still looking for specifics re: non-fiction…tense and POV. I’ve written a spiritual book, based on my experiences. I have been told to re-write it in present tense, though much of my spiritual evolution was in the past which is why I used past tense. Any advice would be appreciated.

Loved the article! Thanks!