Not that many children’s book authors think about the pacing of their book.

But pacing is incredibly important — it’s the difference between a child becoming bored, and wanting to read your book again and again.

When authors do think about pacing, they usually make this common mistake: they think that faster pacing is always better.

Well, not exactly.

Pacing is a delicate dance between two extremes:

- Too slow of pacing: you lose your young reader’s attention

- Too fast: you may overwhelm and bewilder them

Here are the places where you should speed up the pace, and how you can do it.

And just a reminder: if you wanted to read my in-depth advice about how to write a picture book in general, look at “12 Steps to Writing Your Children’s Book.”

1. Modulate your Pace

You don’t want your entire book to be fast paced, and you don’t want your entire book to be slow paced.

It’s best if you slow down the pace in some sections (because they’re reflective, or quiet) and then speed up.

The trick is knowing WHEN to slow down and when to speed up. I’m going to talk about some key places in your book and how you should handle the pacing in the next section…

2. Common Mistakes

I’ve edited more than 1000 children’s books and these are the most common mistakes I’ve seen authors make with pacing.

- Speeding up during climaxes

- You might think it’s a good idea to make a climax faster, but this is a common misconception! Your little reader has been waiting the ENTIRE BOOK for this moment, and if you speed through it, they’re going to be disappointed. Make sure to linger on the emotionally satisfying parts of your book where everything is resolved.

- Slowing down during the resolution

- Children’s book writers often make their resolution twice or even three times as long as it should be, which leaves the reader feeling like the end of the story is dragging. After you have the climax of your story, you really only get 2 – 3 pages to wrap everything up. All the tension of your story is gone, so end quickly!

- Starting with a slow pace

- You must start your book quickly. As quickly as possible. Introduce the main problem or conflict on your first page, or at least by your second page. When writers start the conflict a third or half of the way through the book, I have to gently tell them that this is the true beginning of their children’s book.

3. Understand “Page Turns”

You control pacing in your children’s books through “Page Turns.”

This is the approximate amount of time it takes for a child/adult to turn the page. If a child turns the page after 2 – 3 seconds, that would be super fast pacing. If a child turns after 8 – 15 seconds, then you’re creating a slow pace.

You control that pace in two ways:

- the amount of text on the page

- the complexity of illustrations on the page

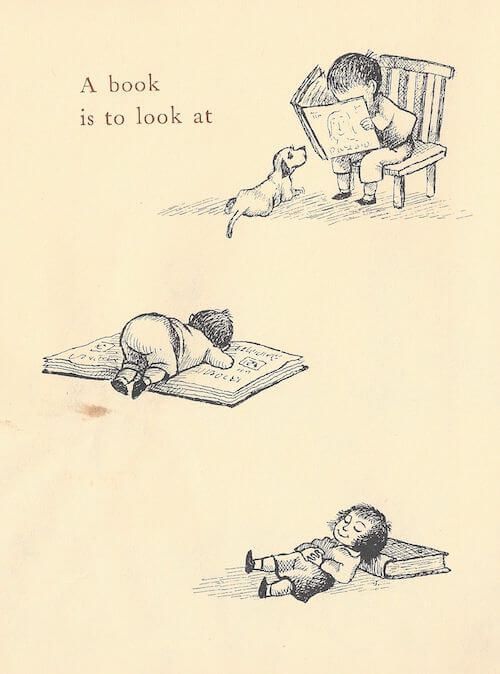

So look at this example:

There are only six words! And the images are incredibly simplistic. This is an example of a quick-paced page.

Now let’s look at a slow paced page (and once again, this isn’t bad — it’s about authors knowing and having control over their pacing).

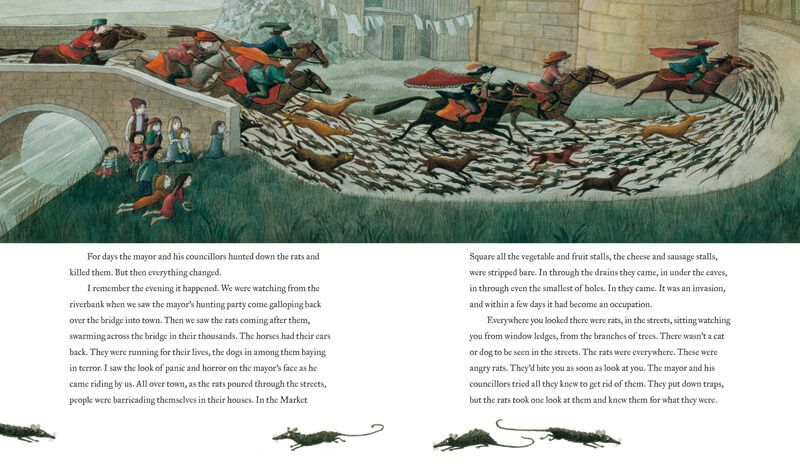

Here is an example from Michael Morpurgo’s The Pied Piper of Hamelin:

It’s slower not only because of the massive amount of text on this double page spread. It’s also slower because there is so much for a child to look at!

- The river

- the rats

- the children watching

- the little dogs

- the horses

- the laundry in the background

- the clothing of the riders

I could easily see a child staying on this page for at least a few minutes.

4. Use 3-Fold Repetitions

So a really common children’s book technique is the three-fold repetition. Basically, three things happen in a row.

- 3 times the character tries and fails at a task

- 3 enemies a character must defeat to win the princess

- 3 ideas before he comes up with the “right” idea

That’s actually a great way to control your pacing. It often keeps the pacing lively, because the reader is anticipating the next step, and also because there’s nothing between each step — you’re just moving along at a quick clip.

Conversely, three-fold repetition can be used to slow down the pacing, allowing for deeper emotional or narrative resonance. This works well when you want to emphasize the importance or emotional weight of a moment.

With the example below, if you have this all on one page, it would be slow, while if you spread it over over three pages, it would be faster.

Example: A child tries three times to build a sandcastle, with each attempt being ruined by the waves.

“With a pail and shovel, Lucy carefully crafted her first sandcastle. Just as she put the finishing touch—a seashell flag—a wave swept in and washed it away. Undeterred, she started again, this time building a bigger castle with a moat. Just as she admired her handiwork, another wave came, destroying it as well. On her third attempt, she built the castle further away from the shore, her eyes glancing nervously at the sea. The wave came, but this time, it merely kissed the edge of the moat, leaving the castle standing.”

5. Create Contrasts in your Pacing

After a slow scene, have a quick scene.

After a quick scene, have a slow scene.

The power of pacing is created through contrasts. If you have four fast scenes in a row, then the reader gets used to that and it’s no longer effective. However, if you keep alternating between fast and slow, it will create a delightful way for the reader to progress through a book.

For instance, after a rapid-fire action scene, you could let your character rest for a moment.

Example: After escaping from a wolf, the main character Maria finds solace in a hidden garden:

“Exhausted, Maria found herself in a hidden garden. She saw a butterfly gently landing on a blooming rose—it was a moment of peace.”

The observation of the non-threatening butterfly slows down the pace, giving both the character and the reader a moment to relax and reflect.

6. Controlling Sentence Length

If you write in short sentences, the pace will feel fast (most of the time).

While if you write in longer, complex sentences, then the pace will feel slower.

It’s best not to only do one or the other. If you want your story to feel fast in a certain section, then go ahead and write a couple of short, staccato sentences in a row.

While when you want to slow down the pace, then write a long sentences, perhaps three or four parts, with depending clauses and conjuctions and all that jazz.

7. Where to Speed Up the Pace

There are certain sections of your book that should read quickly. If you have a lot of text in this section, you’d want to break it up among multiple pages so the reader is turning pages quicker and feels like the story is moving fast.

Here are places to speed up the pace:

1. Introducing Action

Example: Suppose your protagonist is racing against time to find a hidden treasure. Use short sentences to convey urgency.

“Jake sprinted through the forest. His eyes darted. Left. Right. The map trembled in his sweaty palms. Time was running out.”

2. Building Suspense

Example: If your story revolves around a mystery, quick pacing can enhance the thrill.

“Clues piled up. A torn letter. A hidden room. Every discovery led to more questions. Who is behind all this?”

3. Achieving Emotional Highs

Example: In joyful or emotionally intense moments, quicker pacing can elevate the mood.

“Sarah opened the box. Balloons burst into the air. Confetti showered down. Her heart leaped. A puppy!”

8. Where to Slow Down the Pace

Contrary to popular belief, not all moments in your story should be high-octane. Slow pacing is necessary:

1. To Set the Scene

Example: If your story is set in a magical kingdom, taking the time to paint that world helps.

“The kingdom of Eloria was unlike any other. Each leaf on every tree sparkled in shades of emerald and gold. The rivers sang lullabies, and the sky, a tapestry of pink and lavender, promised dreams that always came true.”

2. To Develop Characters

Example: Use slower pacing to provide insights into a character’s thought process or backstory.

“Emily sat by the window, her fingers lightly touching the locket her mom had given her. She missed the stories her mom used to tell, the cookies they baked. Time seemed to stand still as she drifted into her memories.”

3. To Evoke Emotion

Example: In emotionally heavy scenes, slowing down helps readers process and feel.

“Grandpa looked into Tim’s eyes. ‘You know, courage isn’t the absence of fear. It’s choosing to act despite it.’ Tim felt the weight of Grandpa’s words, each one settling deep into his heart.”

9. Check Your Pacing

Say you’ve written your children’s book, and you want to see whether you’ve gotten the pacing right!

Here are three steps you should go through to see whether it’ll be a success:

- Storyboarding: Lay out your text and rough illustrations to visualize the pacing (before you write, obviously)

- Read Aloud: This is a great way to gauge pacing, as you can listen for natural pauses, moments of excitement, or instances where things may drag.

- Get Feedback: Share your picture book with people who are both familiar and unfamiliar with your work. It’s also beneficial to have children in your target age group review it.

- Ask them: were you bored anywhere?

- And also observe their body language as you read: did they seem extra squirmy in any parts?

- Pay attention to any page they want to linger on, and any page where they want to move ahead quickly — they are telling you which parts are fast paced and which parts aren’t

Once you check your pacing, then you should revise, revise, revise, until you get it just right.

10. FAQ

Q: How does font size and style affect pacing?

A: Different font sizes and styles can subtly influence how quickly a reader moves through the text. Larger fonts and bold letters can create a sense of urgency, while smaller, more delicate fonts might encourage a slower, more contemplative pace.

Q: How does dialogue affect pacing?

A: Quick, snappy dialogue usually speeds up the pacing, while longer, more introspective dialogue tends to slow it down. Choose the dialogue style that best suits the pace you’re aiming for at different moments in your story.

Q: Does the genre of the book impact pacing?

A: Absolutely. Adventure or action books often have a faster pace compared to more contemplative or educational stories. Keep genre conventions in mind when determining your pacing. There’s no right or wrong type of pacing — different children will enjoy different types of books.

Q: How many characters should I include to maintain good pacing?

A: Too many characters can slow down the pacing because each one requires some introduction and development. Stick to a limited set of characters that serve the story to keep the pace flowing smoothly.

Q: Should I avoid certain types of sentence structures to maintain pacing?

A: No, you shouldn’t. If the sentences get too long, they might confuse younger readers, but in general, try to vary it up between shorter and longer sentences.

Q: Should I consider different pacing for different age groups?

A: Absolutely. Younger children may need a quicker pace to maintain interest, while older children might appreciate more complex narrative structures that naturally require a slower pace. But there are plenty of exceptions to this general principle!

Q: How do interactive elements like flaps or textures affect pacing?

A: Interactive elements can slow down the reader because they offer an additional layer of engagement. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing but should be considered when planning your pacing.

***

If you’ve crafted a children’s book that you’re proud of, you should strongly consider submitting it to us here at Bookfox Press. We pride ourselves on not just publishing books, but nurturing stories and the talented authors behind them.

We work intimately with you to refine every nuance of your book, including its pacing, ensuring that it resonates with young readers from start to finish, and handle all the messy and complicated details of publication (ISBNs can be confusing!).

When you choose Bookfox Press, you’re not just getting a publisher; you’re gaining a dedicated partner committed to your success.