In five to ten years, A.I. programs will be writing novels.

Not great novels, certainly, but readable novels.

Many writers and readers might scoff at that kind of prediction, but for those who disagree, try proposing a different timeline: 15 years? 20 years? Well, in the span of human history, that’s not too distant, is it?

To argue that it will never happen seems laughably naïve. Given the current linguistic proficiency of machines, and the rate at which they are progressing, the clock is ticking.

The big question for writers is: how will they deal with AI competition? (I answer that at the end of the post — keep reading to find out).

But first, let’s look at how AI will start writing novels.

5 Things AI Needs

What does an AI program really need to write a novel? It needs data.

These are the five things that AI programs need to start writing entire novels:

- Examples of novels. Programs now have access to roughly five hundred million novels, and that number is growing every single year.

- They need the tools to understand that data. For instance, how to parse a character description and action and dialogue to create a mimicry of characterization on the page.

- Programs also need to be able to weight novels that sold well as more valuable in their matrix of information than novels that sold poorly, and therefore learn from the “best” novels.

- Programs also need to understand structure. To imitate the predictable patterns of first chapters, rising action, reversals, surprises, climaxes, and denouements.

- As far as genre, they would need to figure out the patterns. The patterns inside romance novels, detective novels, fantasy, sci-fi, and similar genres, and then mimic the language, locations, and character development.

No, we’re not there yet, but there is a clear route forward, and an obvious financial incentive for programmers willing to tackle this task.

Current AI Programs

We already have many sophisticated programs on the market which can write nonfiction, a genre that’s markedly easier than fiction. ChatGPT is the most obvious one.

And then there are Writesonic and Article Forge, both good examples, both of which promise to write blog posts, headlines, essays, articles, and more, with zero plagiarism.

The nonfiction these programs write is … passable. Meaning it’s plausible that a person of average intelligence would write a piece of about the same quality. It feels a little flat and boring, but it’s still functioning on a fundamental level to communicate information to the reader.

Sure, the programs’ writing requires deleting some paragraphs and rewriting some sentences, but guess what? Editing is also required for text written by human writers.

ChatGPT, Sudowrite, Inferkit, Jasper, and ShortlyAI offer not just nonfiction writing but story-based fictional writing as well. They are all based on an open-source software named GPT-3, and their fictional efforts are, at least for now, rudimentary.

They’re best at suggesting ideas and narrative routes to the human writer who might be experiencing writer’s block, and offering up a few elementary paragraphs.

But if you look at the timeline of these type of programs, they’ve only been in existence for a year or two. What happens in five years, in ten years? What happens with exponential growth of machine learning and data sets?

Now, just for clarification, I’m not talking about programs that merely rewrite your sentence. That’s just fiddling around with grammar. There’s a bunch of programs on the market, like Wordtune, which will do that for you. But that seems a far cry from production of text.

Rewriting programs work more like an editing program than an actual writing program. Which is both less impressive and also irrelevant to having a computer write a novel.

Early AI Programs

Of course there were some messy early efforts to have A.I. programs write novels.

1 the Road by Ross Godwin was written by the computer when Godwin drove from New York to New Orleans with sensory devices hooked up to a computer, and the computer turned it into words. But there isn’t exactly characters or plot – it’s more like poetry than a novel, or at best a highly experimental nouveau roman novel, like your refrigerator magnets got scrambled by an infant or a highly intelligent monkey tried to imitate Robbe-Grillet.

It produces snapshots like this:

“Eagles Nest Diner: a american restaurant in Goldsborough or the Marine Station, a place of fish seemed to be a man who has been assembled for three days.” Unless Finnegan’s Wake is your all-time favorite novel, I’m betting you don’t want to read a whole book of that.

But now there are far more advanced collaborations between humans and A.I. programs.

Over at The Verge, there’s an article that talks about how author Jennifer Lepp has used A.I. assistance to write her novels under deadline.

When her brain was squeezed dry of inspiration, she simply let Sudowrite describe one of her characters, a pixie, and the computer figured out the character was supposed to have bright red hair.

When she asked Sudowrite to describe a lobby, it gave details about “crystal chandeliers, gold etching, and marble.” The A.I. program definitely isn’t writing the entire book for her, but it’s a partner, a collaborator in the process of novel creation.

And for the last nine years there has been a A.I. version of NaNoWriMo (where novelists try to write a 50k-word novel in November).

In this version, called NaNoGenMo, coders try to write code in 30 days that is capable of generating a novel. At the end of the month, the coders are supposed to post the novel and the code that wrote it, so it’s all open-source and sharable.

As Book Riot notes, most of the examples from this exercise are mashups of existing novels, such as Leonard Richardson’s Alice’s Adventures in the Whale, which combines Alice’s Adventure’s in Wonderland with Moby Dick.

It’s all very primitive, very prototype attempts, but it also gets you thinking about what a good coder could do with millions of novels and better coding that uses machine-learning.

Is AI Really Writing?

It’s important to remember that A.I. programs won’t necessarily write novels like we do.

A chess program doesn’t think intuitively like a human, judging between the three best moves or recognizing positional patterns, but simply uses brute force calculations to arrive at the best position.

But you’re missing the point if you think computers can’t understand emotion, or human psychology, or poetry, and therefore could never write a good novel.

The computer doesn’t need to understand any of those things: it merely needs to mimic the language that creates that emotion in the reader.

For instance, a human would think of their tumultuous relationship with their father, and create a father/son confrontation with accusations of verbal abuse and lack of love. The emotion on the page would exist because the author feels that emotion deeply and drew from a well of personal experience.

On the other hand, a machine would create emotion by consulting a database of 50,000 father/son confrontations set 65% to 80% of the way through a book, and screen for details:

- Percentage of dialogue to action

- Word count of the scene

- Presence of any other people or animals

- Number of exclamation marks

- Any interruptions from outside forces

- Sensory descriptions (smell, touch, sound, taste).

- Types of dialogue spoken (insults, evasions, defenses)

- Physical actions, such as violence

So what the machine would be doing would be complex imitation.

But at a certain point, when you blend so many stories together, it feels original – or at least original enough.

And given the human propensity to “borrow” ideas and materials from other sources, we can hardly blame machines for using the same tactics.

Art is theft, as Picasso said.

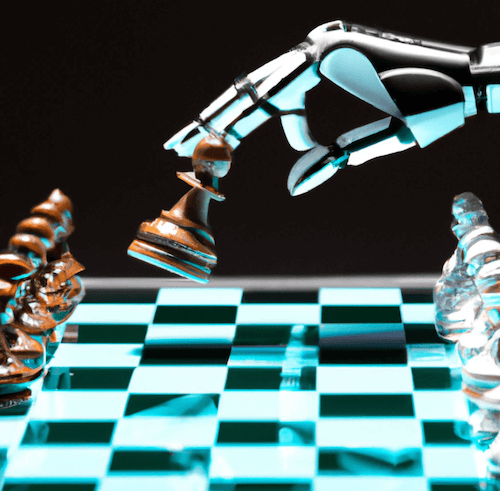

Chess AI

Looking at machine learning in other categories gives us a glimpse at the future of A.I. novel writing.

For instance, look at the three-stage evolution of chess programs.

- At first, humans were easily able to whip chess programs, by guiding them into complex scenarios where their computational power petered out in the face of the exponential rise of potential moves.

- But at a certain point in the early 90s, a grandmaster paired up with a chess program was more powerful than either a chess program alone, or a grandmaster alone. An A.I./Human combo united the best of both worlds.

- Except that only lasted a few years, until we witnessed Kasparov being defeated by Deep Blue in 1997 (where he claimed the IBM side had cheated by combining human intelligence with the machine, which was untrue). Since 1997 onwards, computers have decimated every grandmaster in the world.

Keep that three-step progression in mind (poor execution, powerful A.I./human combo, A.I. superiority) because it’s essential to understanding how computers progress in other categories.

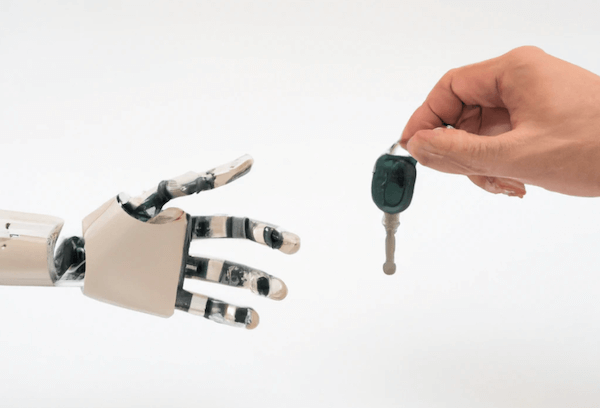

Self Driving Car AI

Self-driving cars is another analogous scenario of the progression of machine learning.

Self-driving cars are in the middle stage of the three-stage development described above. Right now, a human driving a car with assistance from the computer is safer and more reliable than either a human driving alone or a car driving alone.

In twenty years, the technology will likely advance to the third stage, where computer-driven cars are vastly superior to human drivers, and it will be considered borderline irresponsible (and dangerous) for a human to take the wheel.

Also, remember that self-driving cars show a remarkable step forward in the abilities of A.I. to deal with complex, real-life situations.

We have technology in cars to “see” stop signs, to “see” pedestrians, to guard against accidental lane changes, and to adapt in a physical environment to unknown stimuli and dangers. This is light years beyond the ability of the chess programs to make computational decisions inside a closed, fixed, rule-governed sandbox of a game.

If you don’t think computers will gain virtuosic linguistic abilities, you are not a student of history. It happened with chess. It’s happening with self-driving cars.

It’s happening with the visual arts, especially painting, with programs like DALL-E 2 and Ai-Da. Recently, Jason Allen won the Colorado State Fair art contest by generating artwork using a program called “Midjourney.”

If you are a betting person, it would be exceptionally unwise to bet on a verbal limitation for A.I. programs (but if you really want to take that bet, I’d be happy to fleece you).

Where Are We Now?

Are we there yet? Not quite.

Right now, A.I. programs like ChatGPT are at the initial stages of being able to write a novel. If you read a short sample, it would show flashes of passable prose, but also sections that don’t make sense or connect to anything else.

In the fiction writing world, we’re just on the border between:

- The first stage, where the efforts of A.I. are far inferior

- The second stage, where the human/machine combo becomes stronger than a writer alone.

(For clarification: in this context, the strongest writer doesn’t necessarily mean the person creating the highest art, but simply the writer who can pump out books quickly and sell the most copies. I understand that’s a dubious definition, but for the purposes of this article, let’s run with it).

The Future

In the near future, for instance, the writing process might follow this pattern:

- A human asks a computer to write ten novels in an hour.

- The human skims the concepts of several, decides which one is worth editing, and then takes a week to make revisions.

- They publish a book that week, and another the next week, and a third by the end of the month.

With the assistance of an A.I. writing program, it’s entirely conceivable that an author could “write” and publish a novel every single week. In this type of future, A.I.-assisted writers will financially squeeze out the writers who insist on “natural” writing.

And then eventually, as computers advance in their understand of the nuts and bolts of fiction, get better at evaluating structure and get a larger data set, computers will advance to the third stage and be able to write a book all on their own that’s better than what 95% of humans could write.

I know, I know—the hackles of every writer just rose.

You might be cursing my name.

You might be shaking your heads in disbelief.

But if you look at the millions of self-published books coming out every year, the bar isn’t always super high. There are weakly drawn characters, stilted dialogue, plot holes, and inconsistencies across the board.

It is that inconceivable that a computer could at least match that? And eventually learn from mistakes and write something a little cleaner and more polished?

And then it comes down to production: if a computer can write 10,000 novels in the time it takes a human to write one, several of those ten thousand novels will be better than the average human novel, and it becomes a trick to just find out which ones are better.

Filtering becomes more important than generation (which isn’t dissimilar to our current predicament, with more books than we have readers).

Natty or Not?

Body builders get this question all the time: “Natty or not?”

Meaning, are you natural, or do you take steroids and other enhancing stimulants?

Soon, authors will be asked this question as well: Are you a “natty” or “natural” writer, or do you use artificial intelligence to juice your storylines?

The fact that every human writer receives help from a host of humans – beta readers, developmental editors, copy editors, proofreaders – is beside the point. Editing and advice from humans seems permissible, but having a computer write your book would deserve disclosure.

Will AI Ruin Writing?

Well, no.

- Because computers haven’t ruined chess.

- And self-driving cars won’t ruin driving

- Despite its ability to whoop the ass of the greatest Jeopardy contestants, IBM’s Watson hasn’t put a dent in the number of barroom trivia competitions.

- DALL-E 2 hasn’t stopped artists from picking up a paint brush.

Even if computers are able to write novels, and eventually to write good novels, that won’t detract from the fact that writing fiction and nonfiction is healthy for the human soul. Humans will still have that desire to type the words themselves, to write something only they could have written. Humans will never stop writing, just like we’ll never stop trying to beat our friends at chess.

Publishing Will Change

But computer-written novels will change the structure of the publishing industry.

Imagine a publishing house that didn’t use any human writers at all. One that only employed a team of editors who reviewed A.I. written novels and then selected and edited the best ones.

- There would be no royalties to pay.

- They would be able to pump out novels faster than readers can consume them.

- It would be a streamlined production cycle, a revolutionary advance in how stories are created. It might also be gross and anti-human, but I’ll resist the urge to pass judgement: I’m just describing a probable future.

I’m sure there will be many Luddite publishing houses who will refuse to publish A.I. written novels, earning brownie points by publicizing to the writing community that they have a strict humans-only policy, but then the question becomes: who will be able to tell?

We’ve already seen pranksters use computers to write academic gobbledygook and get it published in the rarified air of academic journals, in which intelligibility is not a virtue but a flaw.

In the world of A.I. written novels, those novels would be largely indistinguishable from human writers, and some miscreant will ignore the guidelines, pull a prank with the Luddite publishing house, and then publicly brag about it.

What Should Writers Do?

Let’s say that you believe what I’ve written so far in this piece. And if you’re a writer, you can see the exponential curve of computer intelligence, and know that yes, your job is threatened (or at least a sea change is coming).

In that case, what are human writers supposed to do?

This is my recommendation: start writing human novels.

Remember that one of the greatest advantages to human beings is flexibility. We adapt. We change to our environment. We grow and learn in creative and exceptional ways, making leaps and inferences that most computer programs would only dream of.

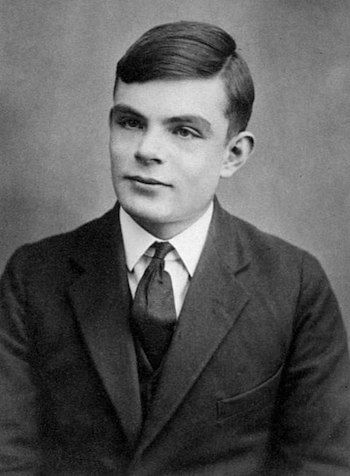

Turing Test

We can see this in the Turing test.

The Turing test, first created by Alan Turing in 1950, says that if a computer can trick a human into thinking it’s a human being through a text-only medium, it is a huge milestone in A.I. development (because it’s said that computers can “think” – although really it can just imitate thought).

But the Turing test wasn’t routinely put into action until 1991, which held the inaugural Turing test. Humans and machines had 5 minutes in the early years to convince the humans on the other side of the screen that they were human. Still, the humans would beat computers for the next twenty-three years. Until 2014.

In 2014, there were a flurry of news articles about how the Turing test had been won, by a chatbot pretending to be a 13-year-old Ukrainian boy. The computer won by tricking 33% of the human interrogators into believing it was human. The younger age and the nationality gave the computer an edge, though, because there were all kinds of things a young teenager wouldn’t have known.

But then humans changed the game—extending the time from five minutes to twenty minutes, and adapting new strategies to weed out the human and machine.

Yes, machines have been improving rapidly, but so have humans, devising fiendishly clever ways to trick computers. By using humor, by using sarcasm, by becoming more personal or emotional. Humans fought back and began to beat the computers once again.

Just like the arc of the Turing test, human fiction writers are going to need to adapt.

Archaic Book Formulas

If you’re writing commercial fiction that relies heavily upon simple characterization, plot-driven language, and formulaic structures, you will be the first to be crushed by machine learning.

Think of an old-school series like Hardy Boys, which enlisted ghostwriters to pump out unlimited books, and which has a strict set of rules and guidelines for what is and is not allowed. Books that formulaic are ripe for a computer-dominated takeover.

Or look at James Patterson books, which he doesn’t even write any longer but has hired a whole team of writers to flesh out his visions. They follow extremely predictable patterns of plot, with only the details and locations changing, and with only minor variations in characters. The writer of the future will be a James Patterson-imitator with dozens of computers working under him or her.

Both the Hardy Boy series and James Patterson books are essentially robot books.

They are written by people using the machine-like parts of their brain to create stories, just lining up the predictable narrative dominoes in a row, and those are first type of writers who will be put out of business in the new world order of fiction writing.

Write Human Books

To write human books, you have to really tap into what makes you human. For instance, the parts of you that are least imitable by machines. A machine-proof version of a novel would have these types of ingredients:

- Use instinct when constructing your storyline. Don’t do a beat-by-beat imitation of a popular narrative.

- Draw from the peculiarities of your life. The stranger the details, the less likely a computer can imitate it.

- Pay attention to language. AI programs are best when it comes to mechanical prose, instruction-manual prose. And even when they write poetry, it’s more like doggerel. Use language that is surprising, a deft turn of phrase. Create a human “style” that feels unique to you.

- Create deeply human characters. Characters inspired by people you know, with complex psychologies.

- Explore more emotion. Not just the typical, expected emotions. Contradictory emotions. Counter-intuitive emotions. The complexity of human emotion is a deep cavern that humans are best at mining.

- Focus on categories where humans have the advantage.

- Humor is a huge one — we’re better at this than AI.

- Sarcasm is hard to imitate.

- Subtlety is absolutely powerful and innately complex.

- Subtext is very difficult for machines to understand.

If you look at the list above carefully, you’ll realize that literary novels are the safest by far.

Literary novels use original structures, dive into poetic or more complex language, and specialize in deep characterization. The typical canard, which is true, is that they focus more on people and less on plot, and when you’re competing against a machine, that comes in handy.

Imagine a computer writing something like “Beloved” or “A Confederacy of Dunces.” Seems impossible, doesn’t it? And I’d agree that we are light years away from that.

But now imagine a computer writing a formulaic, dime-store romance, and it seems far more plausible.

Bestselling AI Novel

Let me end with a vision of the future, a vision you have to prepare yourself for. One day an author will hit the New York Times bestseller list, and reveal a huge PR stunt: their novel was written with the help of an A.I. program.

Maybe 30% of it was computer-created.

Maybe 60%.

But that will be the beginning of the sea change. The programs will evolve, and writers will start using them in order not to fall behind in the publication race.

In the end, this type of event raises all sorts of moral questions:

- Do you think that a book that bears your name should have been written by you?

- Are you deceiving your readers if you don’t disclose that you used A.I. assistance?

- Are you deceiving your readers if the A.I. wrote the whole damn book?

- And what counts as “written” by you?

- Is it unethical to have a human ghostwrite for you?

- If not, why would it be unethical to use a computer?

- Is it written by you if you went through and edited the computer-generated text?

- And finally, once the novelty has worn off, it is more pleasurable to generate everything out of your brain rather than co-writing with a machine?

- And the deeper question: is it more pleasurable for the reader? And if they can’t tell, would they still prefer to connect with a human brain rather a machine?

Personally, I can’t imagine writing a novel with an A.I. generating the ideas. Mainly because I like independence and prize individuality.

But I’m 42 years old. I don’t understand Tiktok. I can’t see the appeal of most viral trends. I’m decades away from cool. I have limited comprehension of the new generations popping into their teenage years with weird fashion trends.

But somewhere out there is a four-year-old or seven-year-old that will grow up with machines beside them or inside them every moment of the day, programs that guide their every step and thought, their lives inextricably interlaced with quasi-sentient robots, and they won’t even think twice about collaborating with a computer to write their first book.

Indeed, for them it might feel like the most natural thing in the world.

***

Thank you for reading. Please leave a comment if you have an idea about how fiction writers and A.I. will work together (or not work together) in the future.

And if you’d like to read more, here is a much, much shorter piece about how writers can resist A.I.

4 comments

Fantastic article. Wonderfully prescient and pragmatic. Given events of the first few months of 2023 , it’s naieve to think the forces changing our world are not happening faster than we can imagine them at this rate and our primary vulnerability is disconnection from other human experience. Thank you for a being a human being who wrote this article.

It starts generating now.

excellent article. as a blogger got me thinking how can can survive the deluge of computer generated content: personal experience and the human touch

I have worked on a novel, which is to be a series, for three years now. And I have just completed the first. My biggest fear is not competing with humans, far not. But with A I. I write with my own mind, sweat and tears. And I would like to thank you for this article.

I have many books to come, and it’s almost devastating to think that I can work so hard at something, and someone cutting corners, could come along and swipe it all away. From not just me but many.

Writing is all I want to do, and I dread the future writers that have no other wants or desires but to put together an incredible story.