Nothing ruins a story faster than bad dialogue.

Good dialogue, on the other hand, can be tricky to write. It takes more than putting the quotation marks in the right place and adding some dialogue tags.

But Bookfox is here to help. In this post, we cover all the tips, tricks, and secrets you need to write your best dialogue—and transform your fiction.

The Fundamentals of Dialogue

The first steps for effective dialogue come before you even write a word. Considering these principles from the start can ensure you build your dialogue on a strong foundation.

1. Is Dialogue the Right Tool?

Dialogue typically works best for these purposes:

- Revealing or developing characters

- Establishing tone

- Advancing the plot

- Managing pace or tension

Don’t use dialogue for this type of stuff:

- Delivering important facts

- Describing people or places

- Conveying backstory or context

So before you struggle over how to write a scene of dialogue, first ask yourself if dialogue is what you really need.

2. Consider Character Motivation

Consider the lengthy explanation of the villain’s master plans in movies and cartoons, such as The Incredibles, where they’re directly satirizing such absurd explanations.

There’s a reason that scene always feels a bit ridiculous—the villain has no logical reason to let all their cats out of the bag.

Dialogue that grows from narrative need—rather than character motivation—will read as forced or overly convenient, no matter how well it’s written. Just as you need a reason for engaging your characters in conversation, they need a reason for speaking up.

The more thoroughly you know your characters, the easier it is to identify their motivations.

Is there something they want from the conversation? Is it in their interest to say what they say? If not, they—and you—are probably better off keeping their mouths shut.

And remember: their motivation doesn’t need to be huge or earth-shattering. For the right character, boredom might be reason enough to start talking. For others, maybe they just hate awkward silences.

3. Understand Their Desires

What do your characters want? It’s an important question for all aspects of writing fiction—especially dialogue.

Characters don’t talk in a vacuum. They bring their wants, needs, fears, and regrets to the conversation.

And rarely (if ever) do characters want or fear only one thing. They’re like real people that way. At any given moment, we have countless conscious and subconscious desires affecting what we do and say.

- Jay Gatsby doesn’t just want to throw a good party. He wants to impress people and prove himself to Daisy.

- Frodo Baggins doesn’t just need to destroy the ring in the fires of Mount Doom. He wants to protect his friends, avoid the pull of darkness, and eat second breakfast.

- In “The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao,” Oscar doesn’t just want to lose his virginity. He wants to prove to himself that he’s worthy of love.

With dialogue, we think of these wants and needs as agendas. We need to be conscious of the many agendas fueling each character if we want to write our best scenes.

4. Oppose Their Agendas

It would be hard to find two people who agree on absolutely everything. It would also be pretty boring to watch them talk.

Great scenes grow out of characters with conflicting agendas.

Imagine, for instance, a married couple getting ready for bed:

- Maybe one of them is stressed about their busy plans for the weekend and wonders if they should cancel their dinner reservation.

- Meanwhile, the other one had a long day at work and just wants to go to sleep.

- They might both be hopelessly in love and devoted, but right now, they want different things.

Or look at this example from Emily Bronte’s Wuthering Heights:

“If I were in heaven, Nelly, I should be extremely miserable.”

“Because you are not fit to go there,” I answered. “All sinners would be miserable in heaven.”

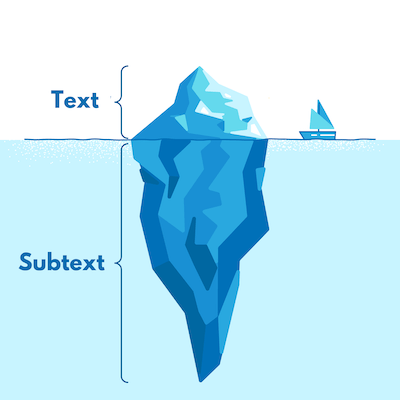

5. Use Subtext

The tip of dialogue’s iceberg is the explicit subject. The hidden part of that iceberg—that’s the subtext.

Subtext is what’s left unsaid. The secrets beneath the surface, the shared history, the old grudges.

Guess what? The best scenes of dialogue are never just about the explicit subject.

Few writers prove the importance of subtext better than Jane Austen. Austen’s characters are bound by tradition and propriety, their conversations kneecapped by etiquette.

In Sense and Sensibility, Elinor Dashwood and Edward Ferrars secretly love each other, though neither has ever said as much. For one thing, Edward is engaged to another woman. When his family disowns him for choosing a career in the church, Dashwood family friend Colonel Brandon decides to offer Edward the rector position in his parish.

This scene, taken from the novel’s 1995 film adaptation, occurs after Colonel Brandon tasks Elinor with giving Edward the good news. Some specific lines have been altered from the original, but the tension created from that subtext is all Austen.

Writing tip: To increase the tension in any scene, take Austen’s approach of focusing your dialogue’s text on less important topics. Save the big stuff for subtext.

Ways to Stage the Conversation

Once you’ve considered the fundamentals of dialogue, it’s time to think about setting.

What happens around a conversation profoundly affects what your characters say and how they say it. The right setting can instantly add tension and tighten pacing. These next three setting tips will help you get the most out of your conversations.

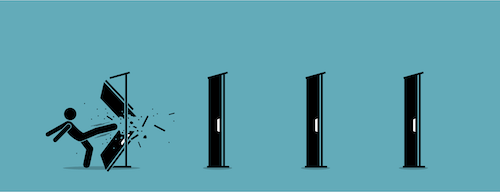

6. Erect Barriers

If you want your scenes to have tension or urgency, give them barriers as well. Barriers are any hurdles that limit the openness or length of a conversation. Anything that stands in the way of your characters saying everything they want to say, in exactly the way they want to say it.

- Interruptions. their doorbell rings just as they are about to answer a big question.

- Danger. They’re trying to have a conversation as bullets whiz over their heads.

- Misunderstandings. They try to tell a platonic friend how they feel, but their friend misinterprets them.

External and internal barriers to open communication are the backbones of good dialogue. Look for opportunities to limit or interrupt your conversations, and you’ll be amazed how much stronger your scenes become.

7. Put Them to Work

The most riveting lines of dialogue can fall flat without action. Two people sitting absolutely still as they talk doesn’t give your readers much to visualize. Such scenes are also harder to pace and sustain because your dialogue has to do all the heavy lifting.

That’s why it’s so important to give your characters something to do with their hands.

In The 40 Year Old Virgin, two guys talk about relationships while smashing long florescent light bulbs. They say a line, they shatter a long bulb against the concrete, and glass flies everywhere. They say another line, and explode one against a wall. The conversation would be so boring if they were just sitting down at a meal.

This tip even applies to settings where action is typically limited, such as on car rides or in diner booths. Your characters can’t suddenly stand up, stretch, walk around, but giving them a task—even a small one, like reading a map or flipping through the tabletop jukebox—can help to energize the scene.

8. Make Them Uncomfortable

To write your best stories, sometimes you have to hurt your characters.

The same is true on the scene level. Choose a setting that makes them uncomfortable, and even the most ordinary topics will be trickier to discuss. It also adds immediate subtext, as long as the whole conversation isn’t about their discomfort.

- If they can’t swim, put them in a rowboat.

- If they’re afraid of heights, consider the top of the Empire State Building.

- If they’re handicapped, put them in a place with stairs

Topics of Conversation

What should your characters talk about?

The subjects they discuss depends on the context and style of your story, but it helps to keep some basic principles of content in mind.

9. Avoid Expository Dialogue

Too often, writers use dialogue as a means of communicating information—even if the characters talking already know that information. This kind of conversation happens for the benefit of the reader, rather than growing organically from the characters and their agendas. We call it expository dialogue—and it can ruin your scenes.

Just look at this example of expository dialogue in action:

“As you know, Susan, you are my wife of ten years. You have always wanted a baby, while I have not.”

“It is true, Marcus, but things have changed recently. You have started to wish you were a father.”

“If only I had a better job. As assistant manager at a drive thru tanning salon, I don’t make much money.”

“But my job as a successful investment banker means we always make ends meet.”

Before this conversation began, Susan and Marcus both already knew their respective stances on having a baby. They knew each other’s jobs and relative income. They have no reason to list the things they already know.

To avoid bad expository dialogue, stay focused on your characters and their agendas. If they wouldn’t need to say something aloud, you don’t need to put it in their dialogue.

10. Know the Point

In early drafts, it’s fine—good, even—to write dialogue without any real purpose in mind. Allowing your characters to ramble on aimlessly can be a great way to get to know them and discover the next twists and turns of your plot.

But in revision, ask yourself this question: What am I trying to achieve in this scene?

Being hyper-specific about your goals can help you determine which lines to keep.

- Are you trying to show your protagonist’s selfishness?

- Are you trying to demonstrate their observational skills?

- Are you trying to show how they’re lying to themselves?

You might choose to use dialogue because you want to reveal aspects of your protagonist’s personality. That’s your big picture purpose. But when it’s time to shape the specific scene, it helps to be more precise about what, exactly, you want to reveal.

11. Stick to Real Time

Dialogue, for the most part, follows real-time pacing. That means it takes roughly as long to read as it would to play out in front of us. We can speed up or slow down the pacing of a scene with narration, internal reflection, or backstory, but the dialogue plays out in real time.

This point is important to remember when determining the scope of your scene. If you want two pages of dialogue to cover four hours of time, you’ll use more narration than dialogue. If you want it to read as two minutes, you can focus more on the dialogue.

Sticking to real-time pacing is especially important when your characters are eating or drinking something. Let’s say you’ve got a scene in a bar where your characters order a round of beer at the top of page one. Unless you incorporate a fair amount of narration on that page to draw out the timing, they probably shouldn’t order another round at the top of page two.

12. Don’t Say Too Much

In real life, people rarely get the chance to express everything they know, think, and feel in a single conversation. Even if we think we’re saying everything, we lack the objectivity and insight to identify and verbalize all our subconscious motivations and desires.

Our characters should be no different. Dialogue that attempts to fully present a character’s perspective on any one issue typically reads as unrealistic. Even your smartest characters can’t know themselves as well as you know them, so resist the urge to put your insight into their mouths.

In Michel Houellebecq’s “The Elementary Particles,” his character Michel is prone to single-word lines of dialogue, such as his response to what he will do in retirement: “Think.”

Pro Tip: When you’re editing your dialogue, your main goal should be compression. Have your characters say less. Cut a third of your dialogue out, and what remains will be much, much stronger.

13. Allow for Loose Ends

Conflict doesn’t automatically bring tension. Your character can face the biggest of problems—detonating a bomb, for example, or interrupting a wedding to steal the bride—but that’s no guarantee readers will be on the edge of their seats.

Real, palpable tension lives in the anticipation of resolution—the pursuit of a desire, rather than a desire achieved.

The best dialogue never forgets this fact, which is why it’s typically best to avoid resolving all issues within a single scene. Loose ends can help to propel your reader forward, eager to see what might happen next.

Of course, sometimes your story will necessitate a more fully-resolved scene. Maybe the star-crossed lovers finally confess how they feel. Or a parent and child have a deathbed reconciliation. But even in those scenes, consider leaving a little something unresolved. Doing so might help ensure the scene sticks with your readers long after they finish the story.

14. Avoid Lengthy Speeches

In Atlas Shrugged, Ayn Rand has her main character John Galt give a 70 page speech.

Please don’t be like Ayn Rand.

Sometimes you’ll write a scene where one character does most of the talking. It can be tempting to just let them talk, filling full pages with uninterrupted dialogue.

But long stretches of one speaker will always feel a little unrealistic. For one thing, it’s unlikely the other characters are just sitting there, completely still and unblinking. Even short sentences where other characters scratch their faces or cough can add realism to longer monologues.

Plus, weaving in description, action, narration, or responses can help to keep your readers rooted in the scene. Dialogue mostly engages our sense of hearing, while other elements help us see, smell, and feel the scene. Don’t let your readers forget where they are or what’s happening, even with characters who like to hear themselves talk.

15. Start Late

Most real-life conversations start something like this:

“Hi Bob. How are you?”

“Good. How are you?”

“Hanging in there.”

“Don’t I know it?”

These kinds of lines always remind me of Fred Flintstone starting to run: he peddles his feet in place for a second before he takes off.

This just isn’t very interesting. Instead, use narration to cover the opening and shift into dialogue when the lines get good.

16. Leave Early

Great scenes of dialogue can turn bad if they go on too long. Once you’ve made your point and served the specific purposes you’ve identified, it’s probably time to move on. Just as we typically don’t need to watch your characters greet each other, we likely don’t need to watch them say goodbye.

This is the opposite of in media res. In media res is the technique of getting in as late as you can to a scene. This is about getting out as early as you can.

Revise your dialogue by deleting about 3 – 4 lines at the end. End on a revelation or a surprise or an arrival.

Nuts and Bolts of Realistic Dialogue

So far, we’ve considered the big picture—the why, where, and what of good dialogue. Now it’s time to get into the nitty gritty sentence-level tips that make your dialogue natural and tight.

17. Use Contractions

In most cases, using contractions in your dialogue helps you mimic the rhythm of real speech. Most people say can’t instead of cannot when speaking, so most characters should too.

There are, of course, exceptions to this rule. If you’re writing historical fiction, it’s possible contractions don’t fit the time period or setting. Or you might have a character who prides themselves on proper speech. And sometimes, even in real conversations, we use the longer form to emphasize a point (ex: I will not take this sounds more forceful than I won’t take this).

But generally speaking, people have long used contractions, so there’s no reason to avoid them in dialogue.

18. Cut Out the Fluff

Have you ever read a transcript of a conversation? If not, you might be shocked how often people say filler words, like well or um. Our daily speech is riddled with the fluff of unneeded transitions and hedging words.

In pursuit of realistic dialogue, it can be tempting to include such words as often as we say them, but doing so can leave you with dull and dragging conversations.

For all our talk about wanting our dialogue to feel real and natural, it’s crucial to remember that we’re not court reporters. Fictional dialogue should feel real, without the boring parts of actual speech. Think of dialogue as stylized speech: like the real thing, only better.

19. Limit the Name Calling

Inserting characters’ names into lines of dialogue too often is a sure way to sound unnatural.

Real people—especially when in conversations with only one or two other people—rarely say each other’s names. They don’t need to. Everyone knows to whom they’re talking.

But in fiction, characters often end up calling each other by name multiple times in a single conversation. Writers likely do this to help pace a line and clarify who is speaking—but we have other tools (like dialogue tags) to achieve those goals.

A good rule of thumb is to limit yourself to using names once or maybe twice per scene. Any more than that can damage the realism of your dialogue.

20. Be Incomplete

Real people don’t always talk in complete sentences. We skip excess language, stop mid-sentence, trail off, forget a word, fumble our syntax. We want to be clear in our writing, but too many complete sentences in a row can make your dialogue feel more written than spoken.

Raymond Carver is a master at the incomplete, interrupted, or wandering sentence. Here’s just one example from his famous story “Cathedral,” when the protagonist tries to describe a cathedral to his blind house guest:

I turned to the blind man and said, “To begin with, they’re very tall.” I was looking around the room for clues. “They reach way up. Up and up. Toward the sky. They’re so big, some of them, they have to have these supports. To help hold them up, so to speak. These supports are called buttresses. They remind me of viaducts, for some reason. But maybe you don’t know viaducts, either? Sometimes the cathedrals have devils and such carved into the front. Sometimes lords and ladies. Don’t ask me why this is,” I said.

Any editor could have a field day correcting this passage’s syntax, but that’s the point: the sentences real people say don’t always follow the rules.

21. Don’t Be Polite

It’s not attractive, but it’s true: real people interrupt and talk over each other. We answer questions as they’re being asked. We stop people before they say things we don’t want to hear. To keep your dialogue moving, reflect characters’ personalities, and sound realistic, allow for interruptions.

To punctuate interruptions, use a dash (—) with no end punctuation, such as in this example from Susan Perabo’s “Indulgence”:

“And I almost got expelled in college for public drunkenness. If I hadn’t known someone on—”

“All right,” she said. “I get it. There are secrets.”

Note that the dash formatting has a more abrupt rhythm than ellipses (…), the alternative way to punctuate an unfinished sentence. Ellipses implying more of a trailing off that a sudden interruption.

That said, readers glance over ellipses, which means they don’t take as long to read as you likely want to imply with a trailing off. If you’re trying to stick as closely as possible to real-time pacing, dialogue tags, action, or description is usually more effective.

22. Be Self-Centered

Real people don’t just interrupt each other more often than we should. We also tune out sometimes when other people are talking. We miss or misunderstand their point. We focus on ourselves—what we’re thinking, what we want to say.

Too much egoism in a scene of dialogue can get tiresome, but allowing your characters to occasionally stop (or never start) listening can add some relatable realism to a scene.

23. Incorporate Slang

In attempts to be sure our readers can keep up with our conversations, we can accidentally sacrifice realism by avoiding the slang, jargon, euphemisms, and abbreviations peppered in real speech.

Take this example of teenagers talking from The Most Dangerous Place on Earth by Lindsey Lee Johnson:

“Let’s see if he has a Facebook,” Abigail said.

“Who would friend him?”

“Just his mom.”

“And Ms. Flax.”

“Oh my God, they’re probably doing it!” Abigail screamed, delighted.

These teenagers would, in real life, probably refer to a social media account as having “a Facebook.” They would use “friend” as a verb and refer to sex as “doing it.”

The slang in this passage is widely known, but even with more specialized jargon, trust your readers. Between their own experience and the benefits of context clues, readers can typically keep up with the conversation.

24. Don’t Repeat Unnecessarily

Even the most experienced writers among us can fall into the trap of too much repetition. Here, we’re talking about characters saying the same thing more than once and repeating what another character just said.

Here’s a bad example:

“Are you listening to me?”

“Am I listening to you? Don’t you see me nodding?”

“You are listening to me? I see you nodding, but your eyes are closed.”

“I’m listening. I close my eyes when I want to concentrate.”

By cutting the repeated question, we get a more natural—and less tedious—conversation:

“Are you listening to me?”

“Don’t you see me nodding?”

“Your eyes are closed.”

“I’m trying to concentrate.”

25. Use Indirect Answers

Do a quick skim of any scene you’ve written. How often do your lines start with yes or no? How often does one character ask a question and another answer it immediately?

Now try cutting those direct and explicit answers to questions. I’m betting you can lose most of them without affecting the scene’s clarity or meaning. That’s because real conversations usually aren’t cross-examinations. People don’t talk as if it’s for the record, so we often skip direct answers in favor of implied answers.

Just look at the last example:

“Are you listening to me?”

“Don’t you see me nodding?”

The yes is implied in that response, so there’s no need to say it explicitly.

Typically, real people don’t use more words than they need to. Even the most verbose speakers don’t insist on exact replies to every question.

26. Incorporate Unexpected Responses

This tip takes indirect responses to the next level.

In real conversations, people leave questions unanswered. They change the subject or just ignore what they’ve been asked.

And sometimes they answer in really unexpected ways. Consider this response as an example:

“Why don’t we go out for dinner?”

“Why don’t you shut your stupid mouth?”

Characters, like real people, can surprise you. Let their dialogue do the same.

27. Allow For Silence

Sometimes, the most powerful dialogue is no dialogue at all.

Consider this brief exchange from Oyinkan Braithwaite’s My Sister, the Serial Killer. In this scene, protagonist Korede is asking her younger sister Ayoola about the man she just killed:

“And his surname?”

She frowns, pressing her lips together, and then she shakes her head, as though trying to shake the name back into the forefront of her brain. It doesn’t come. She shrugs.

Ayoola’s reaction here tells us more about her youth and indifference than any spoken answer ever could.

28. Use Dialect Sparingly

In some classic literature, dialect is an art form. Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God. Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.

Dialect can help bring a character’s voice to life, but when it relies too much on phonetic spelling, it can also be a real chore to read.

For that reason, it’s usually more effective to reflect dialect through syntax, word choice, and grammar, rather than spelling. And when you do alter the spelling, it’s best to do so in small, easy-to-understand ways, such as in this example from William Gay’s “A Death in the Woods”:

“I had a wife looked like Carlene I might stay home with her, too. Keep a eye on her. I ever marry I aim to marry some old gal so ugly nobody else’d ever try to take her away from me. That way I could rest easy and she’d be grateful for any passin kindness I might offer.”

The only spelling dialect in this passage is the dropped –g in passin. Otherwise, Gay uses syntax, word choice, and incorrect grammar to accurately reflect the rhythm and voice of his grizzled Southern characters.

When you do choose to incorporate phonetic dialect, remember that less is more. One or two words toward the beginning of a conversation can establish the voice, and a few words sprinkled in later can sustain it. There’s no need to hit your readers over the head with it.

30. Consider Using Indirect Dialogue

Weaving in some indirect dialogue can help to vary a scene’s pacing and tighten its voice.

Indirect dialogue is dialogue that appears in narrative form, like this example from a faculty meeting scene in Julie Schumacher’s novel The Shakespeare Requirement:

Beauchamp said they obviously needed to rewrite the SOV [statement of vision], but fall, for her, was not a very propitious time. West moaned; they had just rewritten it, he said. Hesseldine also insisted on a thorough revision, but refused to participate himself; furthermore, he vehemently opposed the idea of the task being handled by a cabal of traditionalists. “And by ‘traditionalists,’” he said, still grooming the underside of his beard. “I’m referring to people who haven’t read any of the theoretical or Marxist literature in the past fifty years.

Until the direct quote, this whole paragraph is indirect dialogue. The narrator is summarizing the conversation, often using the exact words the characters said.

Schumacher incorporates a significant amount of indirect dialogue in this scene. It allows her to keep the scene moving without losing the narrator’s voice.

But most of the time, a little bit of indirect dialogue can be all you need to add variety to your scenes.

31. Don’t Exclaim!

This tip really applies to all elements of writing, but it comes up most often in dialogue.

While exclamation marks can be essential for reflecting tone in emails or text messages, they’re pretty weak in fiction. They tell readers someone is excited, rather than showing that excitement in other ways, such as action or description.

- Writer and fiction editor William Maxwell advised writers to use no more than three exclamation marks—per lifetime. So choose wisely.

- Terry Pratchett said, “Five exclamation marks? The sure sign of an insane mind.”

- Elmore Leonard said you were allowed “3 for every 100,000 words of prose.”

32. Set the Pace with Dialogue Tags

Dialogue tags can affect the rhythm of your conversation, so it’s wise to be intentional about their placement.

Consider how the pacing changes based on the placement of these tags:

She said, “We think you should move back home.”

“We think you should move back home,” she said.

“We think,” she said, “you should move back home.”

The first one gives us a little pause between the last line of dialogue and this one — a gap. And the third one really slows down the dialogue.

And it’s not just dialogue tags that can have this effect. Where you position your narration, description, action, and internal thoughts affects a scene’s pacing as well. Reading scenes aloud can help you identify where a pause might make all the difference.

33. Avoid Dialogue Tags

Generally speaking, it’s best to avoid dialogue tags that tell readers anything you could show them through action, description, or the dialogue itself.

For example, compare these two options:

“You never let me do what I want,” he said, like a brat.

“You never let me do what I want.” He stomped a foot and stuck out his bottom lip.

The second one is stronger because we get to see his pouting for ourselves.

In the first one, cut the “he said.”

The Bottom Line

Writing effective dialogue can be tricky, but it isn’t impossible.

And these tips aren’t hard and fast rules. It’s not difficult to find great dialogue that does the exact opposite of any point on this list.

But most of the time, applying these tips can help to elevate your conversations, giving you dialogue that is realistic, revealing, and downright fun to read.

One thought on “Write Fantastic Dialogue: 33 Tips to Spruce up Your Story”

What do you guys think? I’m writing a story…but I just realized that these things were out there. Thanks for the tips.